Window on the World

21.iii.20

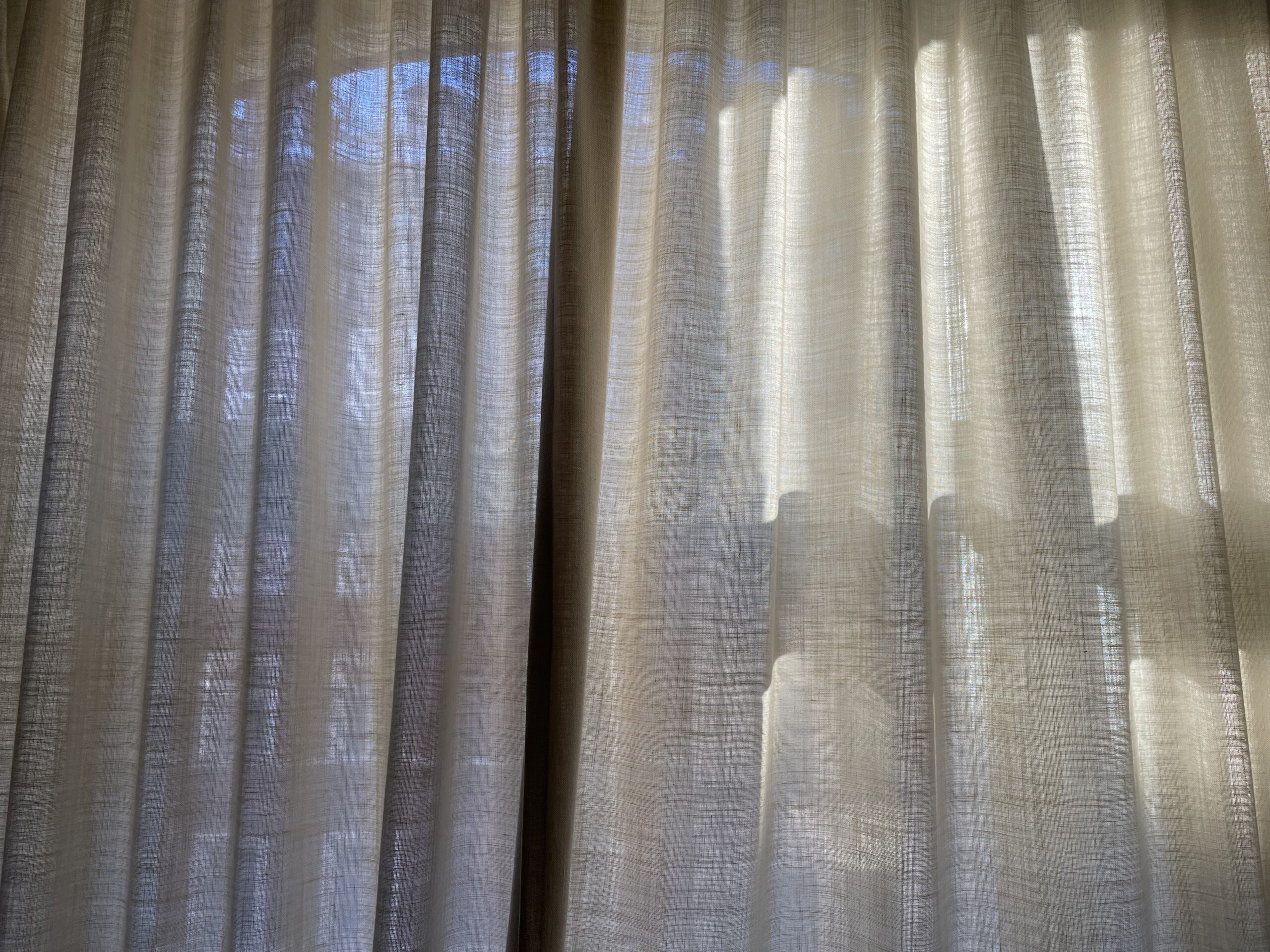

In the room where my desk stands the curtains are drawn. The weave of the fabric is loose enough for the façades opposite to be made out. The sienna red and Stockholm yellow buildings hold little interest for me. But if I raise my gaze above the rooftops, the sky shimmers. For months now this limited patch of infinitude has been despondently grey. At the same time as the city’s great hospital is shifting to military governance, however, the sky is soaring and blue. In a word: irresistible.

Looking at the sky, it’s hard to believe Pascal. Sheltering with the Cistercians at Port-Royal outside Paris, the French thinker noted, towards the end of his life: »All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit tranquilly and quietly in a room.« But in times such as these his words ring wretchedly true. What ought to be humanity’s salvation, the free intercourse with others under an open sky, has become her greatest threat. Still, without collaboration, without joint and considered actions, the threat remains. How to come to terms with this contradiction?

We know by now that the virus does not differentiate among its hosts. Respecting no territorial borders, it attacks us where we most crucially interact with our surroundings: through eyes, nose and mouth. With the exception of the youngest members of the population, who hitherto do not appear badly affected, it avoids what we ourselves have such difficulties refraining from: discriminating. Yet the order of the day is precisely: maintain your distance.

The only mitigating circumstance I can see in social distancing is its proximity to literature. When the pianist Igor Levit live-streams home concerts every evening on Twitter, on one occasion in his stockinged feet, on another wearing a hoodie, he creates community in isolation. This solidarity of solitude has always been the foremost strength of the written word. A book lets its reader be without leaving her alone. It gives her a return ticket to a world she experiences on her own, yet without losing touch with other beings – who may be fictional but are no less consequential for that.

As I lower my gaze from sky to desk I reflect that the seclusion required must remain social. Now that doors are closing nobody should be forced into »splendid isolation«, as Gustav Mahler, much appreciated by Levit, described the weeks during which he withdrew to compose. On the contrary. Levit shows that it is possible collectively not just to keep our distance but to nurse it. This shared but scattered quarantine implies suspension – not least financially. And is surely easier to endure for those of us who have a roof over our heads, a fridge and an internet connection. But it also means: mutual care.

The Germans are fond of linking the emotion to what they call Heimat, while the French think of la patrie. Perhaps the Swedes get closer to the nub of the matter. We say fosterland. That is neither a regional cosy corner of the world nor some symbolic realm built on patriarchal values. It refers to where a person was born, raised and educated.

It is true that I was born of parents from different cultures, in a third country which over the past 75 years has made much of the concept of a folkhem, a »people’s home«. Yet I imagine my real fosterland to be my desk. Nowhere have I spent more time, nowhere have I indulged such strange affects or more frequently been disabused of them.

The desk has changed shape many times over the years. In the beginning there was a rickety thing with a lace tablecloth in a port city in southern Greece. Each morning during a long summer my teenage self, who wanted to revolutionise world literature, had to remove the humiliating tablecloth from under the portable typewriter. But a mere visit to the toilet was enough for my aunt to put it back. To rescue my honour I quietly wondered: what if the tablecloth is a miniature magic carpet?

After that my fosterland consisted for a long time of a door laid across two trestles. There have also been office desks with stickers in the drawers identifying the medical clinic to which they once belonged. And girlfriends’ graceful bequests on gilded legs.

What all these tables have in common is that ever since that summer at my aunt’s I have regarded them as magic carpets on four legs. Among their best features is their ability to transport me anywhere, even to Gehenna or Shangri-La, without my body having to budge. For the past twenty-plus years my carpet with a pilot’s licence has been a structure of wood and steel tubes. There is nobody I have shared more secrets with. If I possessed the muscles for it, the desk would be the first thing I rescued from a fire.

My desks have always been placed in front of a window. It took me a long time to realise this. Perhaps it is due to the kinship between tabletop and window. Both have four edges, both afford mental escape and protection in equal measure.

If I might wish anything for those with whom, in these days of pandemic and panic, I share the distance, it would be such a magic carpet. For the person who manages to »sit tranquilly and quietly in a room«, as Pascal intended, the rectangle offers sufficient ground for further social education. Sometimes it even reminds one of the sky, no matter if it just so happens to be blue.

(For Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung)