Skallarna

(The Skulls)

Information · Cover · Extract · Reviews · Links

Information

Two essays · In Swedish · With Katarina Frostenson · Stockholm: Bonniers, 2001, 45 + 47 pages · Cover: Bo Berling · ISBN: 91-0-057690-5 · English language rights available

Cover

Towards the end of the last millennium, KF confessed that she often thought of beheadings. From the other side of the Atlantic, AF sent her a copy of Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Invitation to a Beheading. Thereafter, a conversation ensued between the old and the new continent that was taken up again with irregular intervals in the course of the next years — always a little more awkwardly, always a little less self-evidently, until AF moved back to Sweden and the tête-à-tête lost its direction entirely. Probably, both writers were relieved by the interruption, even though the topic of discussion did not leave their thoughts. Thus it happened that, one day, when they had recuperated enough courage, they decided to write one last rejoinder each. It was a matter of making common cause in order to have the worries leave the world once and for all. They have termed their collaboration The Skulls.

“As a writer, you spend your life alone at a desk. The sole company are memories, whims, and mistakes, obscure fantasies and forlorn hopes. . . In short: a skull. Is it so odd that you dream of sharing your impasse? At least that is what I did after a period of embarrassment. At last, I turned to Katarina. Thus we decided to trade some last thoughts concerning the container of bone in which writers store their experiences. Different skulls, same worries.” — Aris Fioretos

“The idea came in the middle of the winter: Aris proposed a shared book, an essay each about the points of departure of one’s own writing. The skulls — the word gave echoes, during a few months images rose from their underworld. The space in which the poem begins, the contour of rhythm, the enigmatic ‘speaker,’ and the eternal dream of shining edges and vacant fields . . . It was an adventure to trace one’s own meandering line, in order to cross that of another; to listen to the reverberations of skulls —” — Katarina Frostenson

Extract

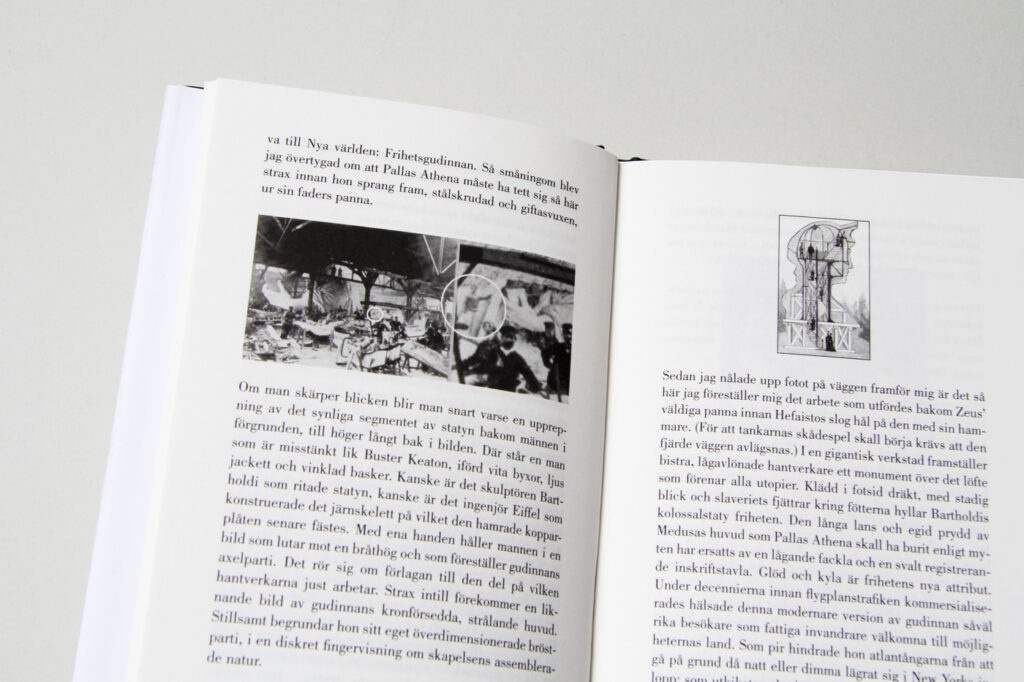

Having made a mirror of the sheets of paper before him, the writer dreads the moment he will have to cast his first glance in it. What if the words do not reflect the mad glory he thought he had felt when he first discovered “his” subject, “his” motifs, “his” obsession? What if he sees only monkey tricks and contortions instead of the effortless grace of thought, the tender movement of emotion? Whom should he then blame for the debacle: his own restless soul or the distorted image before him?

“The harder you look, the less / humans appear human”, Brecht points out in the “Fatzer” fragment. Is that the mirror’s truth?

Confronted with an overwhelming reality, one can either be enraptured and move forward, or begin to doubt and draw back. He who chooses the former strategy will passionately throw open his arms and sooner or later declare himself an affirmer, while he who chooses the latter will cross his and eventually have to live with the label of being a skeptic s c. Gaiety or guile, exposure or enclosure, hospital room or barracks square . . . Any number of opposites are possible, but the trend is clear. Writers are either warm-blooded or cold-blooded.

A theory, much cherished, of why some people dedicate themselves to writing holds that every writer at an early stage has experienced such singular pain or confusion that he spends the rest of his life trying to trace its origins. That would be the definition of a warm-blooded writer: forever seeking the original but obscure energy, with eyes only for those places where things heat up. But if one adopts this outlook, it is surprising that more wounded souls don’t reach for the pen. Perhaps some people write for the opposite reason? Because they realize that they could have been each and every person they encounter in life: the old-timer suffering from dementia, trembling among damp bedclothes in his hospital bed; the kept mistress, as striking as she is blasé, on her way up to the rooftop restaurant of the department store; the laughing child among brightly colored spades and buckets in the sandbox? Anyone struck by this suspicion, convinced of the banality of his own experiences, will dedicate his life to expressing the pain of not being unique. Thus, in his own way, he will grow increasingly different with every passing day.

Another theory holds that doubt is the only thing a writer can trust. As the years pass, he spends more and more time paying attention to himself, since it is there that unbelief has its source. He himself is nothing, he thinks, but if he manages to keep his head, one day he will capture the right nuance of a memory, the exact tremble of a thought, in words — and then he will be able to ascertain his true contour. That would be the definition of a cold-blooded writer. But doubt won’t loosen its grip. Instead it tightens — and with good reason. Incurable gambler that he is, the writer has embarked on the impossible: to get his own brain to show its cards. Henceforth, his work will not be done just because he switches off his writing lamp or pushes aside his paper. In the end, life will not even be sweetened by those moments of calm and oblivion whose coolness once surprised him. His despondency will now deepen into a dike. If he does not put his pen down, eventually he will be forced to entitle himself an authorized paralytic.

“(Might my mind be a magic mirror?)”, Baudelaire asks in one of his intimate journals. The parenthesis encapsulates all the pathos, and all the paranoia, of which writers are capable in unguarded moments. For is it not a desperate version of the call to self-knowledge that has echoed down literature since its earliest days? At once warm and cold, affirming and consuming, orphic and maenadic, the parenthesis erects with one hand what it destroys with the other. As I reproduce the question, I imagine that, seen squarely, it asks: “Mirror, mirror on the wall, what is my mind if aught at all?” The reach of such a request may be extended infinitely, for it holds a yearning as unstilled as the song that once issued from Orpheus’s head. But the question has a reverse side, too. Skeptical, it also asks: “Am I not dazzling myself? Could it be that the real obstacle to insight is my own brain?” If Perseus, instead of using his mirror to see, had held it up as a shield, it is the question that would have flitted through Medusa’s mind moments before her own gaze turned her to stone. Anyone pondering the parenthesis around Baudelaire’s question should not be surprised, then, if he ends up imagining that he is looking at the two hemispheres of a bright, sounding orb, as well as the two handles of a vessel filled with darkness — or to come right out : the ears on a head.

Is it any wonder that the dream is born of a middle way without an attendant whiff of compromise? Can the temperature of a life spent with paper and pen never be allowed to measure a human 37˚C? Sure; why not? Only, the question is who this creature would be. A deadly serious hysteric, perhaps? Or a pessimist cracking a crooked smile? Hard to say. The image that comes to my mind is of the sole being I know who, without losing his honor , would be capable of throwing himself against the wind that tears out of the mirror’s no-man’s-land: Buster Keaton. Gruffly, he pulls up his shoulders and presses his arms to his sides — all in order to reduce the body size. Would he were no bigger than the dark rim of his hat when, grimly but resolutely, he peers through distended fingers. A warm heart and cool nerves — that is all anyone needs who has resolved to get to the bottom of himself. A suitable caption underneath this snapshot might be: “I Become a Social Issue” (the title of a chapter in Keaton’s autobiography). For is that not how one asserts one’s relevance? Against better judgment? Of course, it remains uncertain whether the strategy will succeed. The sole assurance is that only those who see the comedy of the situation will get anywhere.

Towards the end of his pamphlet on drugs, Baudelaire points out that the opium eater has “a dark diviner” by his side, who introduces “foreign elements to his reflective nature”. Perhaps this is the mysterious guide who opens the door when one taps one’s forehead in scant trust of one’s sanity. Introspection? Yet again? As the obliging creature he is, he bows, smiling a suitably ambiguous smile while making a courtly gesture with his hand. A bit of hocus-pocus is called for. Then he straightens up and reads, one finger lifted, the inscription above the portal of the house of bones into which one has just discovered one may enter: Welcome to your brain!

There is no other way. In the grey matter, windows may face outwards (picture windows for some; cellar vents for others), but all doors open inwards. Man exists only as long as he is separated from his surroundings. Stay in your skull or perish! This ossuary may not offer much space, a couple of cubic decimeters at most, but that does not mean that darkness has a limit. For anyone wanting to explore its contents, there is only one rule: regard yourself not with sympathy or suspicion, but with curiosity. The question is no longer who but what one is. After all, the exhortation “Dig where you are standing” rings differently if one chooses, as Lichtenberg, to regard the earth as a skull.

Much in the same way that the dark diviner accompanies the opium eater on his journey through the artificial paradises, Baudelaire’s pamphlet joins de Quincey in his efforts to express “the secret thoughts” in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. In certain places, though, there are shifts in emphasis and perspective. Unlike his precursor, the Frenchman is not out to rid himself of a drug addiction with the therapeutic help of literature. On the contrary, he wishes to establish its superiority as a reality-enhancing elixir. Here, a step is taken beyond a romantic sensibility, marked by the sweet decay of a substance from hell, and into a modern consciousness whose illustrious companion is the guardian of black bile, la Mélancolie. Until then, the art of letters had been regarded as a cure by everyone, with the possible exception of Don Quixote. Baudelaire realized that literature, too, could be addictive. Was it this that Walter Benjamin perceived when, in a text about the joys of hashish intoxication, he pondered Ariadne’s thread? “What joy in the mere act of unrolling a ball of thread! And this joy is very deeply related to the joy of intoxication, just as it is to the joy of creation. We go forward; but in so doing, we not only discover the twists and turns of the cave, but also enjoy this pleasure of discovery against the background of the other, rhythmic bliss of unwinding the thread. The certainty of unrolling an artfully wound skein — isn’t that the joy of all productivity, at least in prose? And under the influence of hashish, we are enraptured prose-beings raised to the highest power.”

Unlike poetry, which requires a maximum of tension and density in the smallest space possible, prose calls for movement, displacement, expansion. It is never the plot that holds a novel together, as laziness or convention might have us believe, but something much frailer: a tone. This tone belongs to neither writer nor narrator, and least of all to any of the work’s characters. It arises in — or rather through — the telling itself. If the tone strikes a chord with the reader, it will take him from cover to cover, through “the magic labyrinth” (Baudelaire) of scenes and tableaux formed by the story, no matter how disparate they may be. For the tone is his thread. Of course it may deceive and bewilder, lead astray or sidetrack, but when it really carries, it always heightens the desire for meaning. The tone, then, is “meaningful” in the genuine sense of the word: without possessing a significance of its own, it harbors enough sense to create that fleeting ground in which the truths of fiction may take root. Thus a primeval forest may grow out of a cloud, a Roman empire out of a haze, and an eighth continent lie extended behind a veil of mist. But to the same extent that the tone leads the reader on, it also dies away. Therein lies half its secret: in a way, it is only when the ball of thread runs out, when we are in the furthest depths of the labyrinth, that we understand. For it is then that that “other, rhythmic bliss” which is the complement of creation occurs. What we call resolution is just the echo which one day will lead us back out again.

The text’s gift to the reader: suddenly it conveys the impression that one owns a skull space in which its particular tone rings true.

If communication is to occur, an interval is needed — between an impression and its recollection, between an image and its reflection, between one skull and another. No echo, no sound without distance in time and space. For anyone headed into a brain this means that they must transform their perception into a tachograph, a device that patiently and minutely records all the impressions, delusions and discoveries lurking in the dark interior. The trick is to catch consciousness red-handed, and thus also to register what one sees but does not understand. Through these visions, half clairvoyant, half idiotic, the traveler creates an echo chamber — a vaulted piece of prose, a psychic sphere. Like the black box found by investigators at the bottom of the sea, in the desert sands, or hanging from the neighbor’s tree, and which describes how an airplane crashed, this psychogram is the vessel’s “soul”. As all records of inner visions do, it requires a receiver, but with this the writer should neither worry nor trouble himself. The black box is a high-tech version of something very ancient: the message in a bottle. It is part of the game that it should survive the sender. Whoever gets the message is always “whom it may concern”.

In the same way that smoking hashish takes one further and further into the maze of one’s consciousness, reading a book leads one into the shadowy windings of a brain. A brain — not necessarily one’s own. For sonorous prose breeds familiarity with a place the reader can only visit as a guest. (This is proof enough that so-called “hypertexts” observe a different etiquette than that hitherto current in literature. In the latter case, a guest would never get it into his head to rearrange the host’s furniture. Or change the menu.) Anyone who has ever experienced the enchantment of this adventure, who has been transformed into a “prose-being raised to the highest power”, will henceforth be dependent on literature. It is not hard to see why: like Ariadne’s thread, it carries home by carrying away.

The dark diviner darts ahead, like a shadow when the sun is low. Briefly he stops and turns around, motioning impatiently towards the dusk beyond the brow’s portal. Come on, then! Following behind him is a vacillating figure with a spade over his shoulder, a ball of thread in his hand and deeply furrowed brow: the prose writer as cranionaut. Like everyone else who goes exploring their grey matter as if it were a new land, he is looking out for interesting places to dig. But any place will do, really. Everything is foreign soil. Goodbye affinity! Goodbye intimate self! For introspection, flair is more important than routine; instinct and patience will do where familiarity no longer suffices. Other than that, all it takes is passion and a clinical eye, plus a suitable dose of good fortune. A timidity here, a trouble there, a few embarrassing insights and a couple of crackling short-circuits from conversations with the ego long discontinued . . . What is literature but an archaeology of the soul, practiced in the interior of that construct known as man?

Pages 5–10. Translation from Swedish by Tomas Tranæus.

Reviews

“Katarina Frostenson and Aris Fioretos speak up about the premises of their writing. . . . Two rather different texts are presented. That of the poet and that of the novelist. Fioretos’ text moves in all kinds of directions — yet there is a very luminous red thread. He deals with the brain. With the infinite complications of a brain. Beginning with reminiscences from childhood, he discusses the dream of a special kind of prose able to keep and enlarge individual moments. A form of prose for which the areas of the brain are just as unknown as once the deserts of Mongolia: ‘After all, it was a question of no less than of showing that the inside of a skull might be wider than a sky.’ This is . . . a text that moves with nimble feet, sometimes levitating, always with a light smile on its lips. There is friendly irony, even well-meaning irony. But it would be a mistake to believe that the demands on the reader are thus lowered. On the contrary. Anybody who has discovered the interior expansion of his skull will experience a hard time settling for less.” — Jan Arnald, Göteborgs-Posten

“J’est un autre, ‘I is another,’ Rimbaud wrote. That might be the motto of the two-headed book of essays that Aris Fioretos and Katarina Frostenson now published . . . The feeling of estrangement — to be somebody else when writing, of thought and word not being part of one’s own body — permeate both texts. . . . They discuss how to listen and to find one’s voice, and through this, how to phrase an inner, almost mystical experience. . . . When you read this book, you nod approvingly and think: Frostenson is Frostenson, Fioretos is Fioretos. The apostle of female language meets the unrivalled maestro of elegant writing.” — Gabriella Håkansson, Dagens Nyheter

“Aris Fioretos’s essay is a sort of corollary to his novel Stockholm Noir of last year. . . . With an echo of Ernst Jünger’s psychonaut, he dresses up in the role as ‘cranionaut,’ a mental traveller through the obscure windings of the cortex, in search of the voice of narration, that ‘brittle tone’ that keeps a work of literature together, and an answer to Baudelaire’s parenthetical but demanding query: ‘(Is my brain a magic mirror?)’ . . . This is an essay in the original, montaignesque meaning of the word, a daring attempt for which travelling itself, lushly accompanied by surprising and learned insights, is more important than the final destination. This is a stimulating, well-phrased, and really entertaining trip.” — Fabian Kastner, Östgöta-Correspondenten

“The Skulls dramatize literature’s wrestling [with that which it is not] in ways fascinating and idiosyncratic. Also, the book provides perspectives on the poetic labor of two of today’s more interesting writers.” — Jesper Olsson, Svenska Dagbladet