Nabokovs ryggrad

(Nabokov’s Spine)

Cover · Contents · Reviews · Links

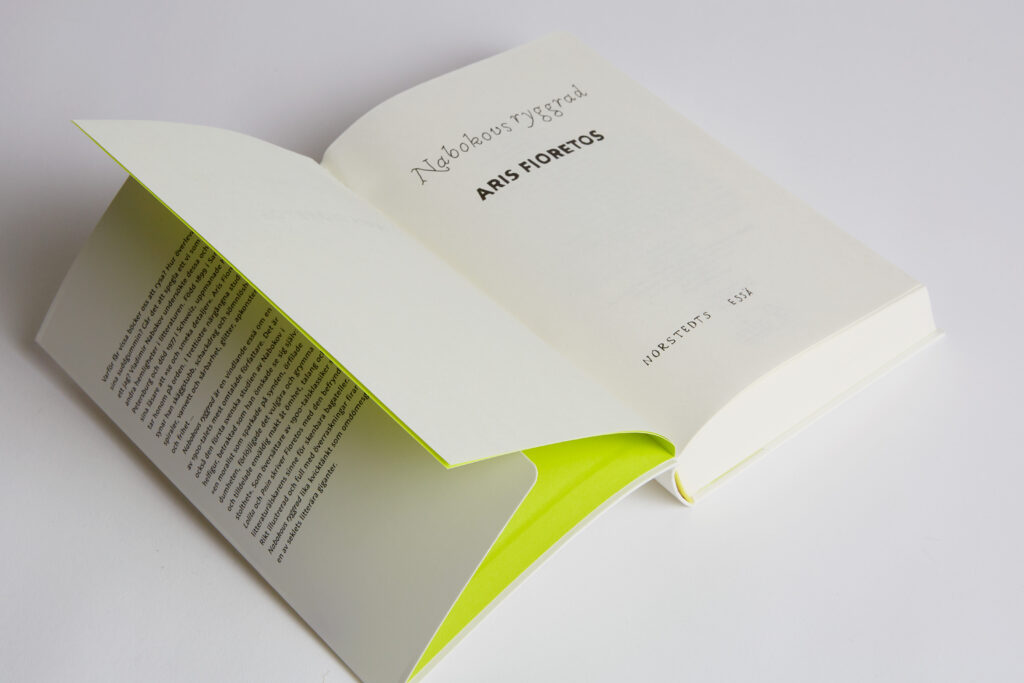

Essay · Stockholm: Norstedts, 2024, 494 pages · Form and illustrations: gewerkdesign, Berlin · ISBN: 978-91-1-313163-4 · Synopsis and English language rights available

Cover

Why do some books make us shiver? How to survive your erasers? Is it possible to reflect a We as an I? Vladimir Nabokov explored these and other secrets of literature. Born in 1899 in Saint Petersburg and dead in 1977 in Switzerland, he urged his readers to »see and caress details.« Aris Fioretos takes him at his word. In thirty-three close studies, he inspects stubble, chess moves and insomnia, spirals, madness and vulnerability, glitter, monkey tricks and freedom ...

Nabokov’s Spine is a winding essay on one of the 20th century’s most esteemed writers. It is also the first Swedish study of Nabokov in full figure, as he wished to see himself: »a moralist: kicking sin, cuffing stupidity, ridiculing the vulgar and cruel – and assigning sovereign power to tenderness, talent and pride.« A translator of twentieth century classics such as Lolita and Pnin, Fioretos writes with a kindred literary lover’s sense of ostensible trivia.

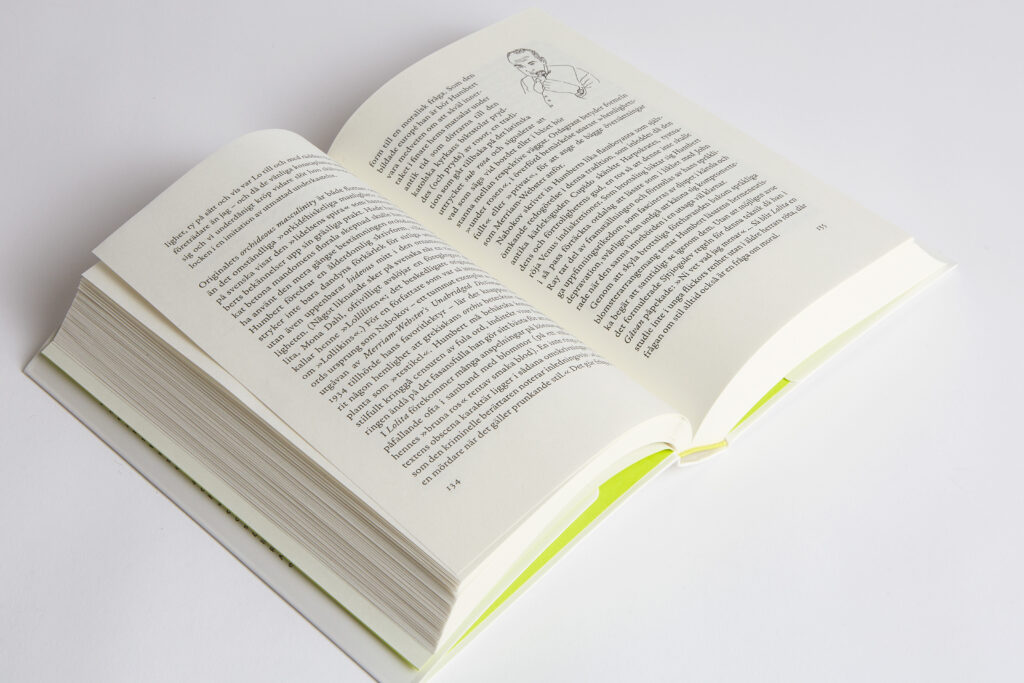

Richly illustrated and full of surprises, Nabokov’s Spine celebrates one of the literary giants of the last century with exquisite skill and judgment.

*

A novelist, Aris Fioretos has translated most of the works available by Nabokov in Swedish. He lives in Stockholm.

Contents

Preface, 9

Details, 29

Elevation, 31 ~ Between the Shoulder Blades, 49 ~ Stubble, 54 ~ Alphabetical Vignette, 60 ~ Get Rid of, 62 ~ Art for Art’s Sake, 70 ~ In the Studio, 79 ~ Then, Afterwards, 84 ~ Camera Obscura, Preferably of the Dutch School, 93 ~ Dissolution, 108 ~ »You know what I mean«, 113 ~ Monkey Business, 138 ~ The Veil of Indirection, 151 ~ Me Too, 158 ~ Three Sighs, 168 ~ The God of Chance, 176 ~ A Name Easy to Interpret but Difficult to Place, 188 ~ Fatidic Dates, 192 ~ Aftermath, 213 ~ And, And, And, 214 ~ Glitter and Other Hazes to the Eye, 229 ~ Freedom between Book Covers, 241 ~ Humidity, 251 ~ Dilation, 258 ~ A Moment of Suspension, 269 ~ The Risky Letter, 274 ~ White Nights, Black Burden, 282 ~ Just the Beginning, 305 ~ Involution, 309 ~ Ecstasy, Protective Tricks and the »I Was Here«-Feeling, 322 ~ Spontaneity, Real and Not So Real, 340 ~ Decreation, or, The Art of Surviving Your Erasers, 356 ~ The Last Word, 376

Chronology, 391

Apparatus, 414

Literature, 465

Illustrations, 479

Index, 481

Reviews

»As a writer, Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) was as stylish as he was serene, paying attention to every word, every nuance, every assonance. To enter his books is to be thrown into a labyrinth from which one will not escape unscathed. Few can offer such a direct reading experience while turning the book over and over like a complicated three-dimensional drawing. You are tempted to explore the smallest corner as if every detail held a beautiful secret. In the first comprehensive study of Nabokov in Swedish, Aris Fioretos grapples with these seemingly incompatible aspects of his œuvre. According to the Russian émigré, a good writer was defined by three roles: narrator, teacher and enchanter. That – as Fioretos notes – it is the second of these which today’s readers find most difficult, especially when the teacher turns into a prophet or propagandist, does not diminish Nabokov’s impact. Instead, Fioretos shows how people embrace him, or rather the narrators of his novels, despite the fact that they are characterized by such an Olympian knack for expression. Nabokov’s Spine is divided into 33 chapters, or ›phenomena‹, collected over almost as many years. Fioretos writes about the importance of the miniscule, about the love of pencils, about how the shiver along the spine is proof of great literature. He goes through most important works, reveals one obscure find after another, and masters the difficult art of reading with a skeptic’s care . . . This is great essay writing of the kind that should be the cornerstone of any self-respecting publishing house.« – Joni Hyvönen, Aftonbladet

»One spring day in 1992, Fioretos bought a paperback in Santa Monica, entitled Transparent Things, and ›fell into a trance.‹ Since then he has read most of Nabokov’s œuvre, translated several of his novels into Swedish, read much of the extensive secondary literature, and now he has given us an absolutely wonderful essay in which he examines the magic tricks, inspects the How and Why, and gives us a master class at the highest level for writers and everyone else interested in fiction.« – Anders Kapp, www.kapprakt.se

»[This is] a long, sinuous essay that deals, in thirty-three case studies, with the ability to caress divine details. Reminiscent of Vladimir Nabokov’s own monograph Gogol, the book is both original and imaginative. And the title? According to Nabokov, there is a bell in the spine of every real reader, which, when we are confronted with good literature, is activated – a spontaneous movement, a trembling, which gives us, in Fioretos’s parlance, ›goosebumps.‹ Reading becomes a reflex thereof, guided by intuition alone . . . Fioretos terms it ›the great alphabetical adventure.‹ A reasonably experienced Nabokov reader will quickly find his way through the book’s labyrinth, and those who for some reason have refrained from becoming such readers will also find their way, thanks to the generous contexts given . . . This is an essay written in a lively spirit. Fioretos is passionate . . . I am greatly taken by the close readings that go to the molecular level in order to figure out how and what and why Nabokov wrote.« – Björn Kohlström, howsoftthisprisonis.blogspot.com

»With his Nabokov’s Spine, Aris Fioretos shows how rereading expands the world . . . He takes my hand immediately. I sit down with him in a café in Santa Monica in 1992, with the newly purchased paperback Transparent Things (1972), which he begins to read only to wake up ›an eternity later.‹ What made him so enthralled? It’s not about ›story‹ or ›recognition‹ or any of the other factors that TV series are expected to emphasize in order to attract viewership. Instead, Fioretos locates the enchantment in how Nabokov uses a seemingly unimportant detail, a pencil found in a drawer in a hotel room, to create an internal expansion in time. By tracing the origins of the implement – the carpenter who used it, the graphite pressed, the trees felled – a drama is suggested that captures an entire history. . . . This book is a work of passion . . . Fioretos’s explanation of what makes readers shiver is based on what he sees in texts, not on how well they illustrate pre-established theories . . . Above all, he demonstrates the importance of re-reading in order to gain deeper insights, to see the invisible fault lines of the author’s magic. Not that the magic that literature creates is merely a matter of illusion – rather, it is a matter of both knowing the world and expanding it . . . Whatever I read next, I want to try to read as Fioretos reads Nabokov.« – Ylva Perera, Dagens Nyheter

»[It is] an absolute pleasure to read Nabokov’s Spine. Aris Fioretos’s essay on the author of Lolita teaches us the art of being a good reader . . . We live in an age of storytelling where content constantly trumps form. Here, at last, is someone who takes the time to discuss form, content, structure and style. What a pleasure to read!« – Maria Hymna Ramnehill, Göteborgs-Posten

»Fioretos has what it takes. His eye for hidden structures and thematic connections between books makes him a pathfinder in Nabokovland. That the shiny surface of the novels hides something else, more intricate, is of course old knowledge, but as far as I can tell, Fioretos brings a lot of new things to the table . . . He appears here as a literary physiologist, if the expression is allowed. How always trumps What. He is interested in how texts work, what they do to the reader and why, which at times boils down to meditations on Nabokov’s motivations. The real excitement comes in a series of reflections on time, whose relentless and dreary flight can still be suspended, albeit temporarily. Authors trying to cheat death is nothing new, but Fioretos has thought more deeply about this than most, showing Nabokov as a magician who stops time with his pen. Only the hunt for rare butterflies gave him the same joy of timelessness[.]« – Fredrik Sjöberg, Svenska Dagbladet

»In one of his couplets, Povel Ramel states that ›it is the small, small details that make it.‹ Vladimir Nabokov could easily have joined the Ramelian chorus. He despised literature built on ›messages,‹ but was happy to repeat his own message about how literature should be built: ›In high art and pure science detail is everything.‹ Aris Fioretos takes him at his word in a richly nuanced essay on the works that accompanied the writer through life . . . It is the details of Nabokov’s extensive œuvre that Fioretos highlights: twists and turns, creases and crevices. But he cannot resist digressions into the author’s biography. That’s great. It is not least when strands of Nabokov’s life are woven into the sly and cunning textual analyses that you feel the telltale tickle in your spine that, according to Nabokov, is proof that you are dealing with real literature. Nabokov’s Spine is an elegantly dressed gentleman en bon point. With its (of course detailed) chronology of Nabokov’s life and works, apparatus, bibliography and so on, the essay is a heavyweight of nearly 500 pages. But the elegant drawings and Fioretos’s stylish playfulness make this great work as light as a butterfly.« – Per Svensson, Sydsvenskan

Links

»Vladimir Nabokov«, Bildningspodden den 12 maj 2024 (In Swedish) · Samtal med Anna Hallberg om »Nabokovs ryggrad«, J! Talks den 19 mars 2024 (In Swedish)