De tunna gudarna

(The Thin Gods)

Information · Cover · Extract · Reviews

Information

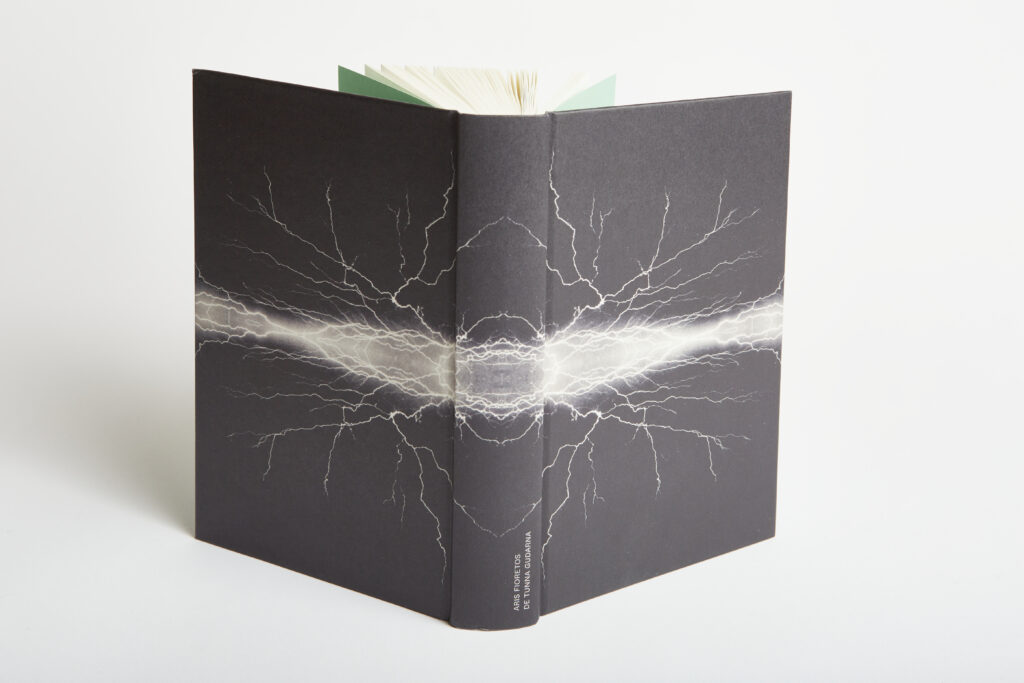

Novel · In Swedish · Stockholm: Norstedts, 2022, 500 pages · Design: Håkan Liljemärker · Cover: Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff · ISBN 978-91-1-312200-7 · Synopsis, extracts and English language rights available

Cover

Ache Middler — aging rock musician in exile, ill of health — receives a letter from the woman he spent a night with twelve years ago. It’s the second time she’s writing, now as then about the daughter she had. The woman asks him to examine himself »inside and out.« In twenty letters to his unknown child, Ache describes proud dreams. Years of hunger. His recklessness. What happens if everything in life can become art? Is loneliness the price of independence? How do you grow old in a culture that celebrates youth and its exuberance?

A novel about male longing and vulnerability, The Thin Gods takes us from an imaginary Alaska to downtown New York, from Thatcherite London and Berlin after 9/11 to a refugee camp on Europe’s south-eastern edge, and possibly to both hell and heaven. This is a story of nerves and electricity, and of a person set aflame.

*

Aris Fioretos lives and works in Stockholm.

Extract

We know it began with the mother. The half-blood who was nothing but bones and gawkishness. Theresa Stern, poet. She pulled off her tank tops, one white, one black, by grasping the hems, arms crossed, and lifting them above her head. Her panties slid away inside her jeans. No bra. For some reason one of her socks stayed on.

Then she stamped her feet so impatiently the alarm clock by the bed fell to the floor. »Off, off, off«, she panted, her lips against Ache’s, as she struggled with his belt. Her nails were short, perhaps bitten down. And painted black.

Ten little lumps of coal, he had thought in the bar where they drank and talked about the starry sky until neither felt like pretending any more. On their way to the apartment lent to her by Dutch friends – the night was warm and humid, the apartment lay above an Asian restaurant – she asked him for a Marlboro Menthol. He wanted to know whose the dog tag around her neck was. She adjusted the scrunchie that kept her hair in a ponytail. Laughing, with the cigarette clenched between gap teeth, she briskly crooked her arm in his; surely explanations could wait?

Three floors up, Theresa pushed the door shut with her elbow and pulled off her tank tops in one and the same movement. Ache hadn’t got his trousers past his thighs before she grabbed his shirt front with a fist and pulled him towards her. They fell onto the mattress. She backwards, he on her hip and chest. The sheet levitated in mild shock before settling – like the forethought neither would contemplate.

Two beings, restless with hunger.

Somewhere a ventilation duct was rattling when Ache awoke. He listened to the unholy but familiar racket for a while, smoking, with Theresa by his side. She didn’t snore, but her breathing was audible. Tranquil inhalations, serene. Sometimes the dog tag she told him had belonged to her father shifted a little. It was turned inwards, so the name wasn’t visible. Actually she’d just said »the old man«; Ache himself added the bit about the father. Her eyes darted to and fro under thin skin.

Once he’d got his clothes on he wondered if he ought to wake Theresa. Instead he picked up the alarm clock from the floor. The battery had fallen out; he checked against his new mobile phone and adjusted the hands. 8.22.

They hadn’t used a contraceptive.

Fifteen minutes later the gleam in the windows on the other side of the canal seemed unreal. The garbage already stank. Hung-over, he continued along Raadhiusstraat towards the hotel. He donned his sunglasses and turned his gaze upwards, to the cloudless sky. Later he learned that a spot had made its way across the sun’s lower rim, dark as dried blood but invisible to the naked eye. Then he thought: a moving bullet hole.

In the bar Theresa had recited poetry while Ache had stuck to old song lyrics. When he’d told her about his dream of merging with the music, bones and all, she’d made a face. Big pretensions. For her part, she considered »lime, phosphorous etc.« to be the lot of humans; that sufficed.

Lime. Phosphorous. He liked the words.

The postcard arrived the following year. Hobo was imprinted across the stamp; the ink weak, the rest was illegible. On the front was an immense night sky with burning chalk specks. The biggest star, in reality a planet, was encircled by a jagged blue ring. Copyright: Planetary Society.

Theresa had written to the record company. Even though Ache had broken his contract they forwarded it in an envelope. Fearful that the company was going to demand repayment of his advance, which he had spent most of, he left it lying among the shoehorns and other things in the hall table drawer. This was how he habitually dealt with anxiety: ignoring the threat until it went away. If he needed something from the drawer he’d feel his wrist pulse tickle. But it wasn’t until Why handed him the envelope late one morning after having slept over that the sense of danger vanished. That was before they moved in together. »Doesn’t feel thick enough for a writ of claim.« Thus he learned what the child’s name was.

His daughter had been born on March 20th, 2005 – at dawn, three days premature. In the minutes after uttering her first scream she measured 19 inches and weighed 5.15 pounds. A world in miniature, defenseless but intact. After her greeting to Ache and the details about the delivery Theresa added: »I just want you to know. Marrow, cartilage, blood – you are everywhere in her. That’s enough.« Unruly characters penned with a biro, blue ink in the looped pouches of the gs.

Ache felt ashamed that the information didn’t affect him as it ought to. He, who had once been known as the Ice King, led a retiring life; relief was greater.

After that, time passed.

Eleven years later Ache received another letter, this time in a thick envelope padded with bubble wrap. When he had been the same age as his daughter was now, something had happened that made him believe he was invisible. Enraptured, he stood stock-still in pouring rain. His lungs felt ethereal, his skin pellucid. Now, six times older, he knew better – yet it still happened that he imagined he had become invisible. Circumstances had taught him it was an advantageous way to live. All senses remained receptive; who Ache Middler no longer mattered. His body became thin as cellophane. He breathed freely.

Why had shared this need to exist without being. A few years before the eclipse – as they called what had happened when he, ill and distressed, had told her about Amsterdam – she admitted that the same longing had made her smoke the crackling powder on tinfoil above the lighter. Ache didn’t want her to start again, so it was best if she believed this new letter contained fan mail. When he slit it open, orange as fire, he sighed and said that some admirers had no limits. Kids’ drawings, really?

Even though his lungs were giving him trouble again, and simple acts such as tying his shoelaces had Ache in a sweat, life finally felt secure. The apartment Mr Deeb had arranged for them was the best thing that could have happened. He owed the estate agent a debt of gratitude now, which Why was not aware of, but if he kept his promise she needn’t find out about it either. Once he had made the journey Deeb wished in return, once he’d returned from hell – »over sea and mountain«, as the poet Ache read in younger years had it – life together would be secure, his white lies in the past. At long last he’d be able to breathe freely.

Ache hid the letter under the stack of English-language newspapers he saved in the study, uncertain of what to do with an envelope seemingly on fire. Afraid that Why would want to see the drawings, he even considered throwing them in the dumpster down in the yard. Then he reread Theresa’s accompanying letter. Her entreaties were so earnest – »tell about yourself for the girl’s sake, for her when she’s an adult« – that he didn’t call back when Deeb left instructions on his answering machine.

Instead he wrote. Ten, sometimes twelve hours straight. In the mornings he would take his tea into the study. Before Why left for her studio he arranged the material for the new record, which was going to be a concept album; as soon as she closed the front door he moved to the computer he had inherited when she’d got a new one. The first memories came surprisingly easily, by themselves. After only a few days he already had several documents. If he became unsure of how to continue in one, he opened another and carried on writing from where he’d left off. Then he got to the time in the band, and to what happened to his brother. At which point things got sluggish. When he arrived at the gigs in Holland and his encounter with Theresa it was as if the clock stopped a second time. Wavering, he put the files in a folder he gave the most all-embracing name he could think of.

Ache knew that Deeb was waiting, so when the estate agent left two messages in one day (Ache wondered if it was by chance that it was on his daughter’s birthday) he continued. The last evening he didn’t hear Why arriving home. She stuck her head in, her brown cardigan slung across her shoulders. Had he been at the computer all day? He smiled wryly. »Almost done …« They had spoken about the new album often enough for her to believe he was working on the text intended to accompany it.

If only she knew.

Long ago, Ache too had written poetry. He even published a collection of poems with his first girlfriend. Nocturnes it was called, typed out on her Hermes 2000 in the apartment on East 11th Street. The collaboration made him realize poetry didn’t impart the same force as music, which he had explained in Amsterdam. When Theresa had wondered why, he mumbled that notes, unlike words, created space for »them«.

»Them?« She didn’t understand.

Sensing he’d said too much, Ache changed the subject. His first stay abroad had been good for him as a musician, albeit not easy. When he’d returned to New York the lyrics were gone from his songs. At last he didn’t need to comment on existence, it was enough to be it.

That made it difficult to get everything into the letters. Still, if he managed to express not just the joy and keenness he’d felt, but also the damage he had caused, his daughter would one day understand why he had to head to hell.

Just the facts, as his grandmother used to say.

From this world between bones and skin.

And what of us, whose words are so tangled?

Will return.

Pages 9–14; translated from Swedish by Tomas Tranæus.

Reviews

»It is a labour of love … There is a nerve in this text which manages to recreate rock music’s search for something new, something grander … In the hands of a lesser talent, it would have fallen flat, but everything is redeemed by a writer who masters the form of the novel so completely.« — Mats Almegård, Focus

»The Thin Gods is vibrating with the ecstasy of rock’n’roll … [It] is also an achievement; here, a whole world is being wrought. Something deeply moving emerges, not least in the final parts when Ache is living as a bohemian artist, half miserable, half successful, in Berlin, with constant money problems and various prosaic means of surviving. At the same time, his dream of weightless tones never dies — the ones that are true beyond understanding and may transport him out of himself while letting him live in complete immediacy.« — Jenny Aschenbrenner, Dagens Nyheter

»Aris Fioretos has written the novel for everyone who dreams of New York’s rock scene.« — Kristian Ekenberg, Upsala Nya Tidning

»The Thin Gods is the story of a time, a culture, a whole world seen through the fates of a few lives … It is an impressive journey in time, through six decades of politics, literature, music, cities, cultures and alternative forms of existence. The novel is intense, beautiful, and melancholy, as well as written with great feeling for the music and literature that play such big roles in the life of its protagonist … 5 out of 5!« — Arne Johnson, Bibliotekstjänst

»The Thin Gods is the tale of the rise and fall of a rock artist. … No, this is not Philip Roth or John Updike. This is the Swedish author Aris Fioretos. What concretion! What poetry! … [The novel] is a mighty elegy, not merely to Ache Middler, but to the pop world at large with its mixture of naiveté and drug abuse, progressiveness and worship of doom. Lovingly and offbeat, Ache tells the story of an era in which one still practiced in basements and garages, making do with tinny sounds far from today’s sophisticated studios. … But Fioretos’s novel would not be what it is if it did not also contain a long row of sharp and tenderly sketched portraits. … The Thin Gods is written in a taut and heaving prose. It has the passion and rage of big metropoles.« — Åke Leijonhufvud, Sydsvenskan

»This fall’s Great American Novel is Swedish and has an intellectual post-punk setting. Aris Fioretos’s The Thin Gods is the equally smart and perceptive story of an artist’s life in the services of rock music. It is about walking in the snow without leaving any traces, about the unavoidable narcissism of creativity and about finally finding one’s life’s why with a capital W.« — Andres Lokko, ETC Nyhetsmagasin

»Aris Fioretos’s The Thin Gods is an elegant novel about rockstar Ache Middler, an Apollinian figure in a Dionysian sphere, a (fairly) clearheaded artist among much wilder colleagues, which brings him success and misfortune in equal measure … The story is brittle and beautiful … Fioretos has always been a masterful narrator.« — Victor Malm, Expressen

»In five-hundred pages Aris Fioretos’s new novel The Thin Gods moves across vast geographical as well as temporal and mental landscapes … His prose is as careful and controlled as the [story’s] composition … The Thin Gods is an incessantly fascinating novel.« — Maria Hymna Ramnehill, Göteborgs-Posten