Alaska

15.iv.23

... but we want to go to Alaska.

– Gottfried Benn

The ceiling fan turns languidly but methodically, an idling propeller. The sheets are in a twist, you awake with difficulty. It is April, the days already bring the heat of summer. Sweat squeezes out of your pores with the mere effort of your breathing. If you trap the air in your lungs you feel a tickle along your hairline. Silver drops slide across one temple, along the line of your cheek. When three or four drops have collected they form a fatter one, which rolls, plump, over your chin, down into your collarbone cavity. You think about the photograph you saw in the newspaper. The boy was sitting on a chair, tears digging furrows down his sooty face. His cheeks looked like a flood plain. In his arms he cradled a lump. When you read the caption you understood what you were seeing: »Moise, 6 years old, with teddy bear. Lone survivor of the fire that took his entire family.«

You cried like a baby.

Later you were studying your face in the shaving mirror. Almost twenty-one. Unwashed hair, feral gaze. You hardly recognised yourself. If your childhood home had been ablaze you wouldn’t have thought twice about braving the flames to save father, mother, sister. And yet you’ve done what you could to be alone. Left, abandoned, the last person on earth. That’s how you wanted it. The thought is ludicrous. You knew that misfortune awaited without kin. If nobody was close to you. If you were never missed. Still you imagined how you abandoned yourself. Not so you might be transformed into someone else, but so you might be the person only you were. Someone without history. What an unspeakable contradiction. At times you would follow the thought so far you barely got back. Then you sensed how it would be. Surrounded by dry, white cold. This wasteland of hunger and clarity.

Now you can only muster the thought: You savage clown. You bereft paradise.

Dread your wishes.

thus opened a novel I began to write twelve, fourteen years ago. At that point the desire to depict the need for radical autonomy had been on my mind for a couple of decades – since the early 90s, when I’d read an article in The New Yorker about a twenty-one-year-old who had abandoned everything that bound him to people, to expectations and commitments, to a history. In short: to civilization.

I saw myself in this Christopher McCandless. After finishing college he donated his remaining bank assets to Oxfam and changed his name to Alex Supertramp. One month later his used Datsun broke down in Arizona. He set his last cash on fire and lived hand to mouth for a year and a half. Slept in the street in Las Vegas, hopped the freight trains that cross the continent in endless processions, worked in the kitchen at McDonald’s in Bullhead City, Arizona. On Tuesday, April 28, 1992 he set off for the last time in his life. He wanted to make his way to the north-easternmost rim of the continent, where he would sooner or later be unable to get any further unless he learned the art of walking on water. Alaska.

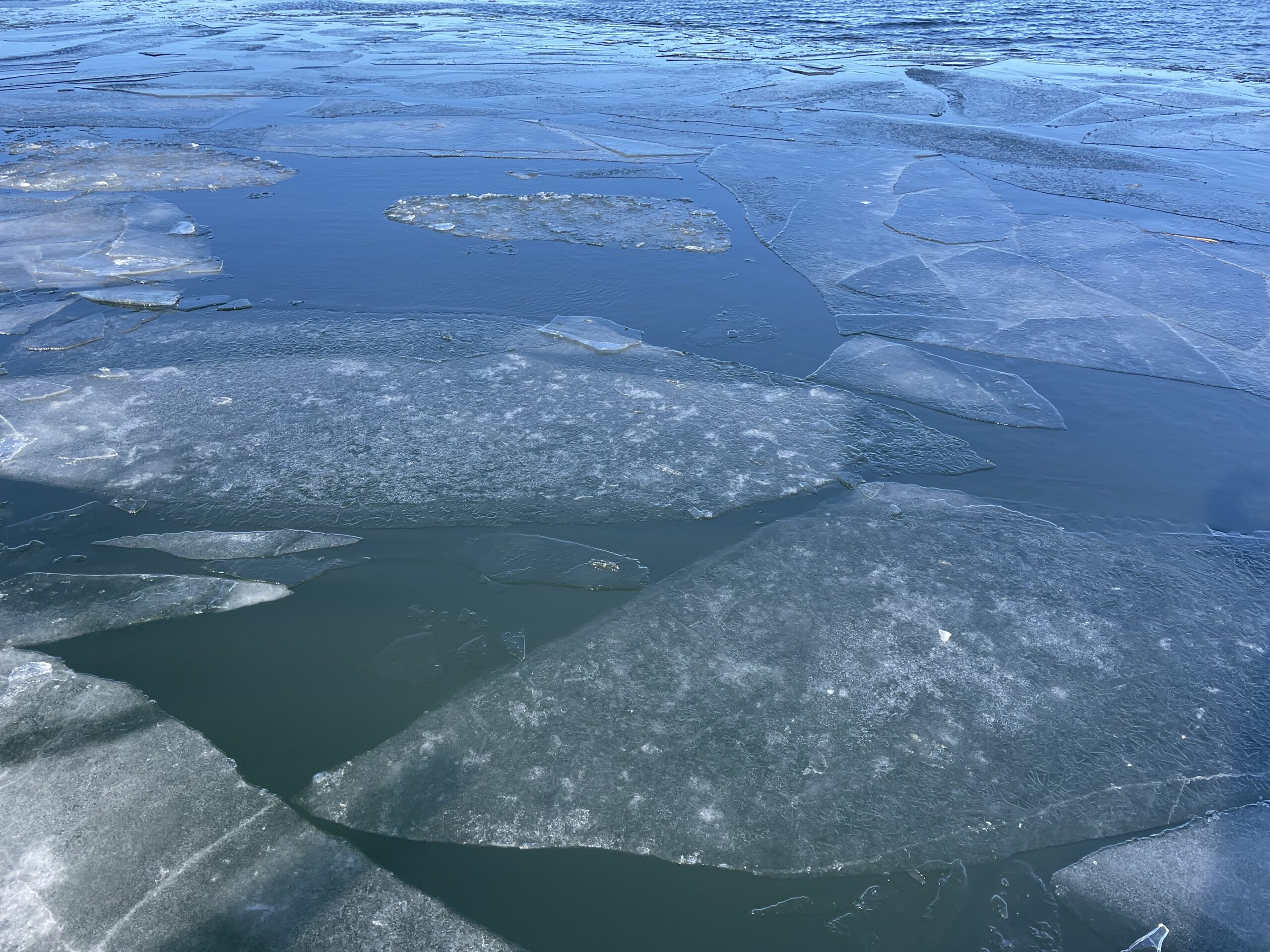

The ice broke up late that year. By the time the waters began to purl in May, Alex had traversed the Denali National Park. Following a series of mishaps he was forced to return to a rusted bus wherein he had sought refuge during the final weeks of winter. Summer arrived, he lived on fungi, berries and water. Read Doctor Zhivago and on August 5 wrote in his journal, exhausted but exhilarated: »Day 100!« Thirteen days later he was dead. Since the renewal of his driving licence, eight months earlier, he had lost almost forty kilos; now he weighed just over thirty. On the door of the bus was a torn-out page from a novel by Gogol. On it he had scribbled a final message to civilization – an SOS – and signed it with his real name.

It is not overstating things to say that the article in The New Yorker awakened my desire to write novels. Until then I had only published poetic prose and essays. I tried numerous angles but never found the right one, so when a book about McCandless’ fate came out in 1997 I shelved the project. Though I ordered the book on Amazon, I never removed the shrink-wrapping, probably out of superstition. Ten years later it was adapted for the screen by Sean Penn. I didn’t see the film either when it opened in cinemas, but a few years later I bought the DVD – two copies, in fact. I let them languish in their wrapping as well. By now I was more than twice as old as the twenty-one-year-old, and had grown so distanced from his obsession that I no longer saw my reflection in his fate. Yet memories of the stalled novel made me want to protect him. As if my original dream would only remain intact as long as I left the wrapping on.

When, years later, I found the unopened packages in connection with a house move, my fancy about personal autonomy was awakened anew. At this point I was pondering what would become my fourth novel. I no longer remembered any details of McCandless’ life, though that mattered less. The only thing needed was what had brought about my initial identification: this will to detach oneself from everything and everyone, no matter at what cost. I associated it with the thirty-first point of the compass, which is to say north by west, and with a name: Alaska.

To this day I cannot easily read or write »Alaska« without experiencing the unruly desire I cited initially – that is, the urge to become »a person without history«. It’s true that I reworked the passage and also moved it further into the book. The six-year-old cradling the charred teddy bear lost his name, the narrator switched gender. The biggest change, however, had to do with neither the style nor the structure in Mary, as the novel came to be named when it was published in 2015, but with the point on the compass. Alaska was no longer the name of a self-imposed exile in north-northwest USA, but of involuntary isolation in south-southeast Europe.

Mary’s older brother Theo, who is homosexual, leaves the family and its nameless homeland ruled by colonels. He makes his way across the Atlantic and possibly to the farthest corner of the North American continent. His sister shared this desire to escape the nocuous bonds that had marred their upbringing in a conservative home. »Anything is better«, she admits, than to »suffocate in this private version of church, family and our sacred nation, as the military calls it.« But when Mary is arrested outside the Polytechnic one November evening in 1973, she has just learned that she is pregnant. She has to protect both her boyfriend, who is one of the leaders behind the student uprising, and the foetus she is carrying – which, she realises, will only succeed if she keeps mum. Time, however, is not on her side. The longer she remains in detention – first at the notorious headquarters of the security police, later on an uninhabited island where she and five other women are forced to clean a prison which is being brought back into use – the longer this goes on, the clearer it will become that she is pregnant. Which would mean that she can be extorted about the boyfriend’s role in the uprising and, if she does not collaborate, forced to have her baby adopted by a childless couple loyal to the regime.

Mary’s silent resistance provokes the military, which subjects her to increasingly grievous violence and finally isolates her from the other women. The punishment is harsh, but at least allows her to keep her pregnancy a secret beyond the third and fourth month – and lets the author depict an existence released from relations but still made of bonds. In secret Mary christens the cement shack, situated by the island’s refuse dump and cemetery, in which she spends her days: Alaska.

In the decades that passed between my original attempt to depict the dream of an existence beyond everything and everyone and the nightmarish conditions of isolation on a prison island similar to Yaros in the Cyclades, over the course of those years my view of Alaska had changed. The name still represented a place of »splendid isolation«. But the snow had been replaced by whitewashed cement, the protagonist was no longer a hungry youth but a pregnant woman, and the bottomless sheet of paper which I’d probably allegorised in my thoughts was transformed into the ravine of stinking rubbish that separates Mary from the cemetery.

Everything was familiar and yet foreign. At last I was writing as I had originally wanted but been unable to because I had stood in my own way. It felt oddly liberating that the compass was now pointing in the opposite direction. And that the boy with the charred teddy I had imagined, this »Moise« with whom I had wanted to announce a new era, no longer had a name. The child hasn’t even been born when Mary lies down on the white floor of her shack and feels the world open not outwards, but inwards:

The cement isn’t softer, but strangely enough something happens which never does when I’m resting on the bed. While I stretch out I wish so intensely that my body take on the form of what’s underneath it, become as resilient and unyielding, that for a few minutes it’s as if I myself disappear. It sounds crazy, I know, and I have no idea how this happens, but I sink through the cement, the bedrock and the groundwater, and still at the same time I am lifted up through the roof and drift out on the wind into the night sky.

I can’t say where I am during these few minutes. I can’t even say who I am. I only know that I wouldn’t end if I ceased.

Twenty-plus years after having read about Chris McCandless for the first time, I learned that it is possible to disappear in a text without going under. And that the strongest bonds are there, in the unsaid, which only beginners see as snow.

In preparation for a conversation with Fiston Mwansa Mujila and Lothar Müller as part of »Windrose. Literatur und ihre Himmelsrichtungen« at Literaturhaus Stuttgart, June 22, 2023. · Windrose on 6/20/23