Heartache

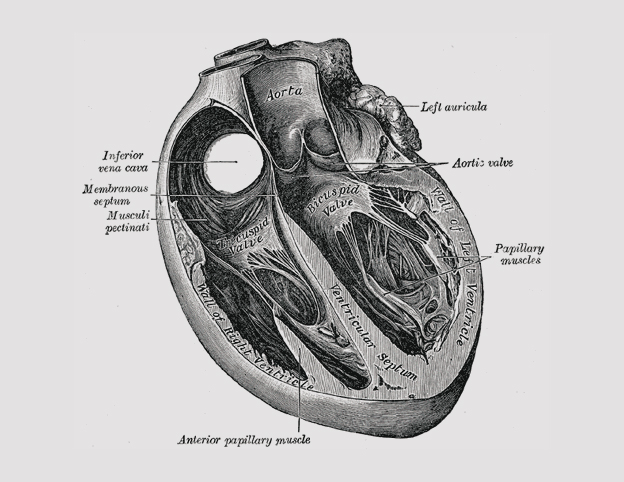

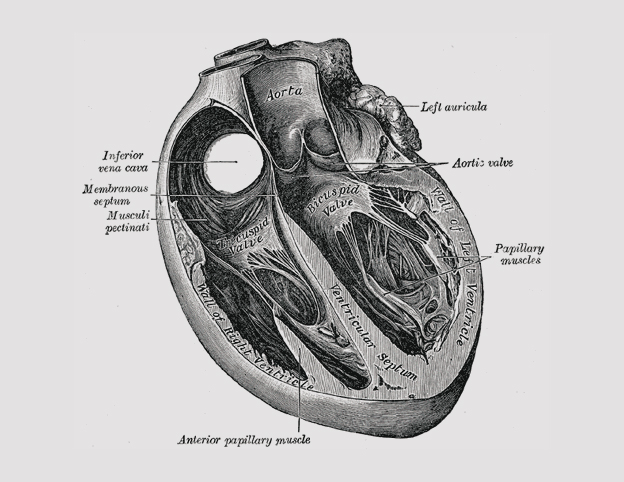

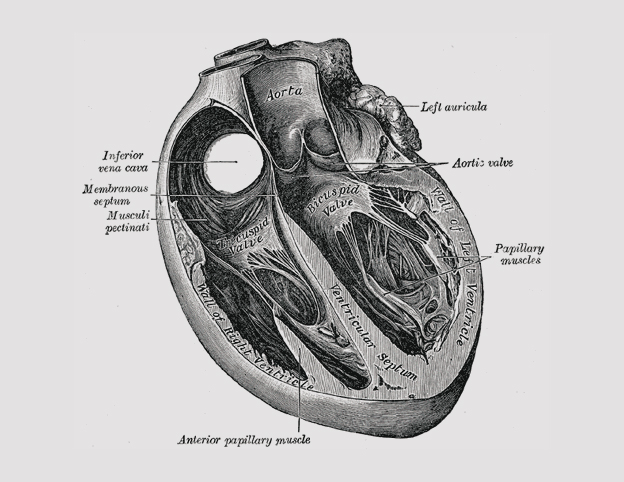

Short story · Original title: Ett ont hjärta · In Swedish · Translated by the author · Dagens Nyheter, August 5, 2001 · Image from: Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body, 1918

She always slept lightly and dreamlessly afterwards, as if made of air. He would lie behind her, soft yet massive, with his arm around her waist and hot mouth breathing in her neck. This afternoon on the couch in faux leather would have been no different, no less dangerous or dear, had she been able, that is, to close her eyes.

As usual, they met after lunch. Now several hours had passed, the sun melting behind the spidery tangle of antennas on the neighboring roofs. Once more, the day eased into that tender haze, with patches of buttery yellow, which, as far as she was concerned, could last an eternity. The white gauze veiling the open window moved indolently, as if an unknown god, silent and sagacious, breathed behind the curtains. This time, though, her body turned neither light nor nimble, her thoughts didn’t dissolve in the smooth afternoon. She turned her head to the side, pressing an earlobe against the hard seam of the arm rest, and studied the brown hole that one of his careless cigarettes once had burnt in the curtain. A fluffy jet of light pierced it, stirring confusion in the otherwise perfect stillness of dust and languor. Her hair, done and sprayed earlier the same day, was sweaty now, and she felt how the creaking leather imitation made a mess of its last claim to shape. He was still inside her, supple like a benediction. But she knew she would soon have to arch her back against him to remain certain.

“Sit down,” he had said when he hired her six months earlier, gesticulating with his eternal cigarette, sinking back into the chair like a receeding wave, heavy with undertow. The smoke had made its last, luxurious whirls as she smoothed out her skirt with hands that had felt curiously constricted. His shirt was white and starched, his tie, a flattened shoestring, had shivered in the flutter of a fan. Then he had run five meaty fingers through his hair and exposed a smooth set of teeth. She had counted to two golden ones before she made a tacit wager with herself: “Yes, two weeks. No more. Then we’ll be lying down and he’ll know me as no other man has.”

In the event, it took four days and the first time they were standing. Shortly before lunch that day, a Thursday, he had sent their colleagues home and knocked on the door frame of her office. She had been sitting behind a mountain of files, pretending not to hear or notice. Gathering the tiny, white cups with soggy coffee grinds in them, he had explained that some friends would be coming over a little later (they played cards once a week), adding that she could leave as soon as she was done with last month’s consignment notes. But instead of returning to his office, he had put the cups down again and, rasing his arm in the air, he had shaken down his fat watch by twisting the hand this way and that — beckoning angels, she had thought, to descend from the fluorescent lights in the ceiling. “Come,” he had continued unperturbed, extinguishing his cigarette in such jarring haste that it had broken in two. “Perhaps there is something that might fit you. For the holidays,” he clarified as he noticed her look. That was shortly before Whitsun, and as she followed him to the storage room in the back, she realized she would lose her wager.

The first time had been short and untender, merely the length of an amazement. With her back to the clothes rack, she had held onto a pair of thin hangers and tried to meet him with panties and hose making a heap of her feet. Afterwards, she had felt heat and embarrassment flushing not only her face, while he was already busy gathering the clothes that had fallen to the floor with ripples of clatter each time he had thrust himself into her. Throwing them over the rack, without looking at her, he offered her one of the new rayon blouses, the ones that had just come in from Paris. (“Paris,” she would later understand, was a storage facility down in the harbor district.) Then he had lit another cigarette, exposed his gold teeth and asked whether she would mind if they got to know each other a little better. In order to gain time, she had tried to straighten out one of the hangers. As she held up the crooked result, both had laughed, and it was at that moment that she realized she had nothing against it.

The second time they had been sitting, the third, too, but from the fourth time and onwards, they had both been supine. A month later, she could not imagine life without these afternoons one flight up on a busy street in the garment district. The sun’s trajectory behind breathing curtains; the icon with its sooty wick in a drinking glass of oil; and the photo on the opposite wall depicting one of the colonels, which he used as a dart board every summer that his nephews from abroad visited; then the chair the back of which he always tucked under the door handle, as if he was a detective in some American movie . . . She knew their world was confined to four walls, last painted when she had still been in school, yet it was wider than any sky.

During the second trip north that fall — he had turned more magnificent with each collection they had managed to sell, while she had eaten less and less — he had thrown out his arms and said it was time to do something about the “situation.” First she had misunderstood him, but when she realized what he meant she felt warmth spreading through crotch and armpits; the heart turning wild with happiness. That night, he made several phone calls. As she applied her make-up in front of the mirror, however, he knocked on her door, sat down on the rim of the bathtub, and, with eyes black and hard, he told her how difficult everything was. They had made love, silent and wretched, and when she woke up the next day, her body ached in a manner she had never known before. She took the twelve o’clock train back home.

He returned a few days later. Without exchanging a single word, they began to meet once a week, on fridays, and she would have considered these encounters its own kind of business meeting, if it weren’t for the fact that he had insisted on talking about the future. Each time, she had pressed a finger to his lips —words weren’t fitting for this — which transformed him into a creature with hungry mouth and unexpected hands. Slowly, something died inside her. Everything went into him, she realized; nothing returned to her any longer. When she was unable to fall asleep this afternoon in November 1972, she understood that she had already made up her mind.

“You know,” she said, surprised at the loudness of her own voice, still half-pondering the slow dust particules that revolved in the jet of light. For a while, she tried to follow a particular scrap with her eyes — slowly, almost lethargically, it moved out of the light, into the rough darkness. As, finally, she lost it from sight, she turned on the squeaking couch and elbowed him in the side. “You know,” she lowered her voice, “I can’t . . . You know, I can’t . . .” Was he really asleep? Again she pushed him in the side — less mildly this time, so that she could hear his cross faintly rustle through the hair on his chest. “I can’t go on like this, I said. And besides . . .”

It took her a few seconds to understand that he wouldn’t answer, another few before she realized he had stopped breathing. Half an hour later, one of the ambulance drivers told her that Stavros Fioretos, 48 years and clothes manufacturer from Athens, had died of a heart attack.