Case Study

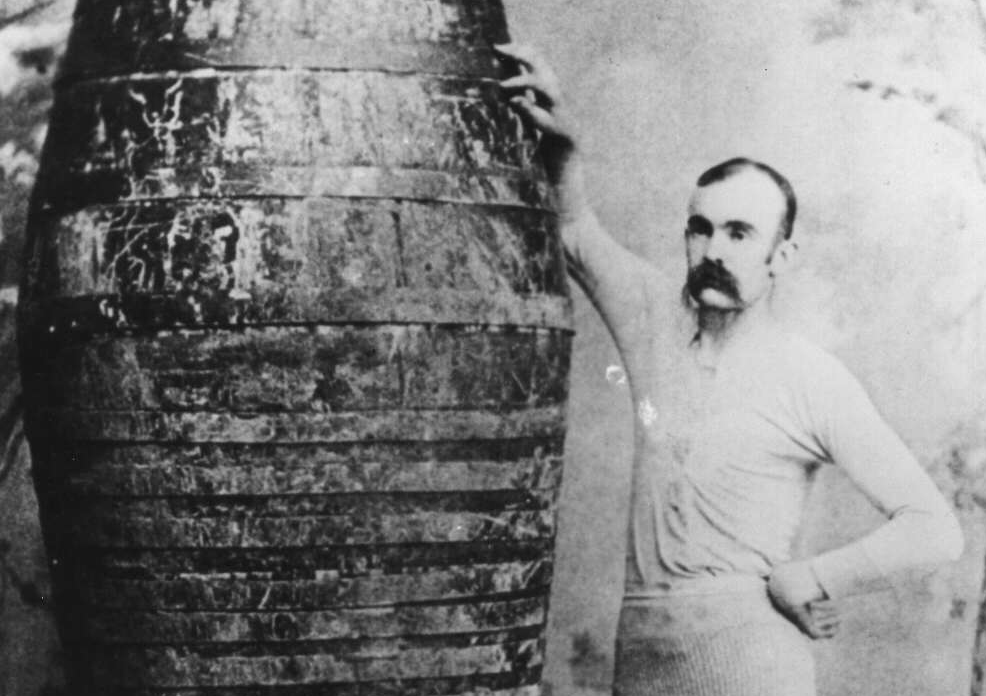

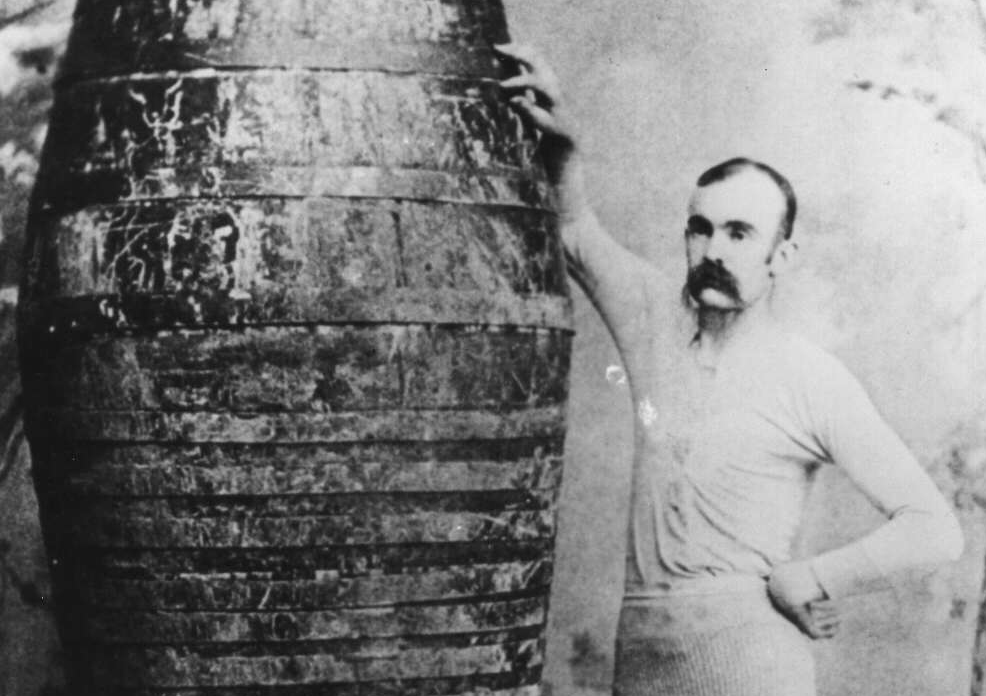

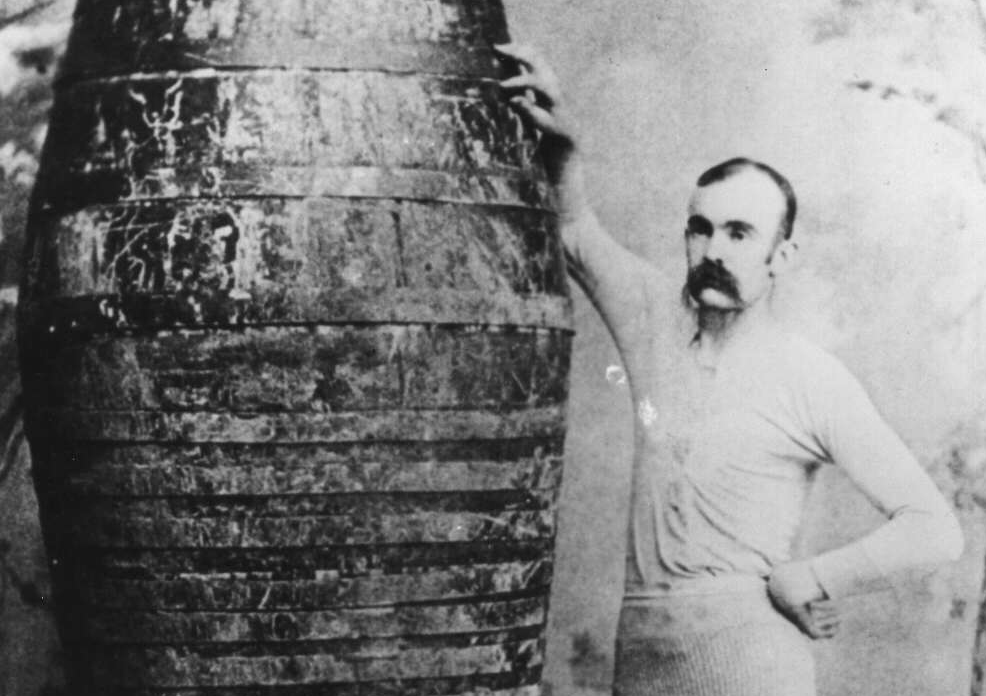

Short prose · Original title: »Fallstudie« · Translation by the author · From Swedish · Merge · 1998, No. 1, pages 10–11 · Photo: Man and his barrel, Niagra Falls, c. 1900

Just as every body emits its specific smell, so does every grave. Mine is no exception. The wood of the coffin is cool and damp, with a faint but umisstakeable trace of rotten fiber. When I press my palms against its sides I sense the chill behind the poorly planed boards. Between two of them, muddy water is seeping in. And behind the casing is a smooth, low-key sort of turbulence, soft, virtually silent, as if engaged in forgetting. In this regard, of course, the coffin is like any other. The tranquility and density, the thick, thudding darkness created when existence is reduced to a few cubic feet or so — the attributes are routine and expected. What makes this coffin different is something else. The air inside has that thin, greenish quality I associate with seaweed and other water vegetation, a sweet and sickly smell I at first found hard to identify. Initially, I thought of moss, soft and thick and mellow, but then it occurred to me that this was not so. Despite the immobility of the smell it did not possess the same peaceful satiation. Instead there was a sort of shifting inertia, if I may put it thus, hovering like silvery dust in afternoon light. Streaks of green made the air at once livelier and more deadly — an odd combination, obviously, as nothing surely could turn more lively or lethal here. Then it struck me: algae. Personally I would have prefered another smell, not necessarily drier or cleaner, but I am hardly in a position to choose. Instead I have tried to get used to the air in the time I have been here. A breath of peaceful putridness; I cannot put it more succinctly. Although the mixed smells of wood, cold, and algae thus gives the coffin its particular quality, this is not all that makes it different from others. There is something else: it is not at rest. Let me explain; the case is not as odd as it might seem. Of course, buried coffins should not move. This is rule number one in any cemetary. The grave is the deceased’s last habitation, and in The Big Beyond he ought to be able to count on peace. Hence a graveyard must be quiet, peaceful, and easy to locate. The only thing others may do is to visit. A name and a date, perhaps a few words of wisdom . . . there is not much else to find. Beyond that, cemetaries are a matter of concern only to city planners. Still, there are other forms of burial. For example, the physical prison that once housed the soul may be burned, leaving the choice of strewing the ashes to the wind or pouring them in an urn which subsequently may be buried or placed in a columbarium. Although not popular, the first solution is used on occasion. I remember an acquaintance, for example, whose last wish was to have his ashes spread on a river in a country to whose culture he felt particularly close. Since it is not legal, at least not without further ado, to convey corpses to other countries, a problem was at hand. The survivors resolved it by distributing the ashes in envelopes divided among them. Each person carried three or four missives, filled with transitoriness. In this manner, they were assured that at least some part of the deceased would make it through customs and into the desired country. One might wonder, of course, who carried what portion of the deceased, and even fear that a few grains of dust might have remained at the bottom of the envelopes after the ashes had been reasssembled. Regardless, however, when the ashes arrived in the foreign country, the dead’s last wish was indeed fulfilled. A motor boat was chartered, and early one morning, before local authorities had rubbed sleep from their eyes, the ashes were strewn over the river. From what I have been told, it took a surprisingly long time for them to sink. Either the surface tension was greater than elsewhere or the ashes were unusually fine. At any rate, they were dispersed across the water, a contentless film of resistence, refusing to dissolve into the new medium. Later, someone claimed that, during a few moments, the deceased had been visible as a thin sheet of paper before the wind wrote him apart. In other cultures the dead is placed on a funereal pire which subsequently is ignited. When the fire finally dies down, nothing is left. On good grounds it could be argued that the deceased, to the extent that rest has been found at last, is buried in the air. Incidentally, I find this thought rather attractive: the dead becomes one with the ether. But the reverse might also happen. At sea, sailors wrap their dead comrade in a piece of cloth designed for this purpose; after ceremony and salute, they ease him overboard. The covered corpse is equipped with weights so that it will sink more easily and, once at the bottom, it will stay there, a swaying stalk of pastness. In the former case, the remains ascend toward the sky and fuse with heaven; in the latter, the corpse descends to the deep embrace of the waters. In both cases the process is vertical, in the direction either up or down, which, I suppose, proves that one may fall both up- and downward. Considering the smell that surrounds me, it would be easy to assume that I have been through the latter. Nothing could be more wrong, however. For me, too, of course, things are going downhill, but find me a person whose time is not running out. Everyone has a deadline. In my case it will turn out slightly different, that is all. I plan to be the first person in the history of burials who will succeed in making the exit and end become one. My ambition is not a revolutionary one, though. I just wish for dying and death to coincide this one time so that, for once at least, first and third person singular may straddle that great divide. Until now, the latter has always succeeded the former, as burial inevitably follows upon demise. But presently I sense real turmoil. The barrel in which I am sitting has begun to sway. The waterfalls cannot be far away now. While there is still time I would thus like to add that I look forward to the historical impact that is bound to be made. The case, one may hope, will be studied.