The Biology of Literature

Interview · Eleutherotypia · April 15, 2006

In what ways do you feel that the fact that you combine many home countries in you affects your writing?

It may have kindled a sensibility to differences. My spine is Greek, my nerves Austrian — or rather Viennese — and my tongue Swedish. But stronger than my loyalty to my three ”home countries” is the sense of not belonging. If anything, I feel like the difference between being Greek, Austrian, and Swedish. For me, writing is not about cultivating identity, but understanding differences.

Do you still have any ties to Greece, perhaps to relatives or friends, or even memories?

My father left in the early 50s and couldn’t return until after 1974. Thus as a child, I never visited. In contrast to my father’s Greece, mine was not a memory but an invention. That’s what you get from being born in the diaspora. You sense your parents’ homesickness, but you’re unable to fill it with your own experiences. In a way, you inhert an empty nostalgia.

Today my parents live here, so I often visit. I know of no better place to write than my father’s ruffled home village on the Peleponnese. I get up at dawn, with the barking dogs and cackling hen, and write well into the heat of the afternoon. After that, there’s short, sugary sleep, followed by a trip to the beach with my daughter. I’m in bed by ten. Same story the next day. Week in, week out. The only thing I miss are the donkies and the three-wheeled moped-cars. You don’t hear them any longer. To me, they were the soundtrack of 1970s Greece.

What’s the connecting point between the different books of your trilogy?

The human body. Each book is about a different bodily organ and the particular way of relating to the world with which we associate it. Hence the first was about the brain — or reflection, if you wish. The Truth about Sascha Knisch is about the sex — in particular the male sex, and in most particular the testicles. Put differently, it’s about instinct. The last will be about emotion.

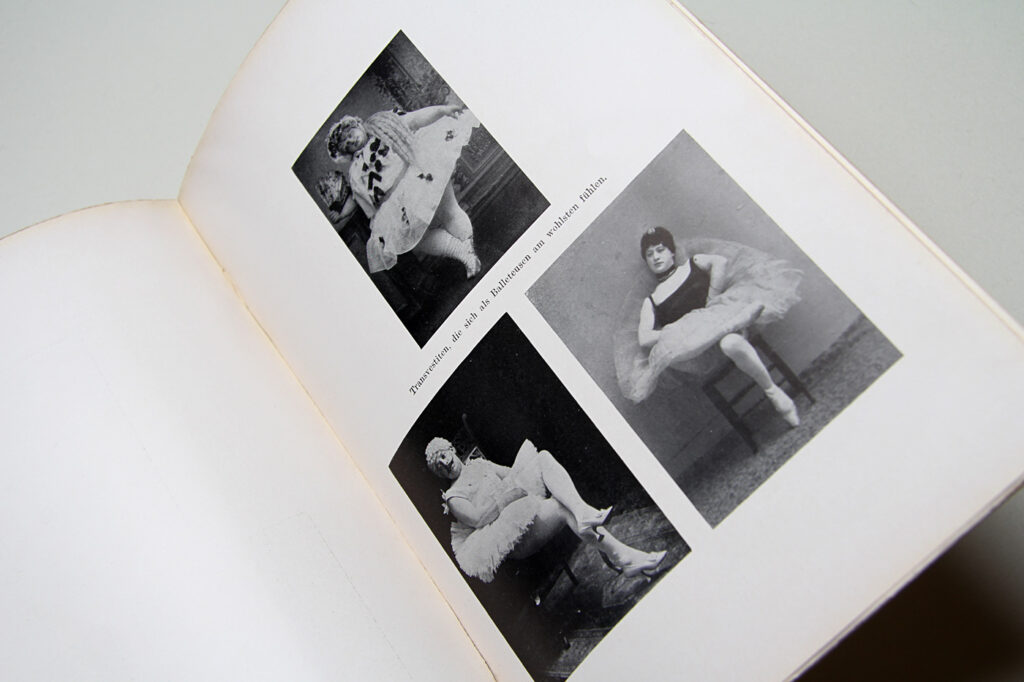

What were your motives behind choosing a transvestite as your main character in The Truth about Sascha Knisch?

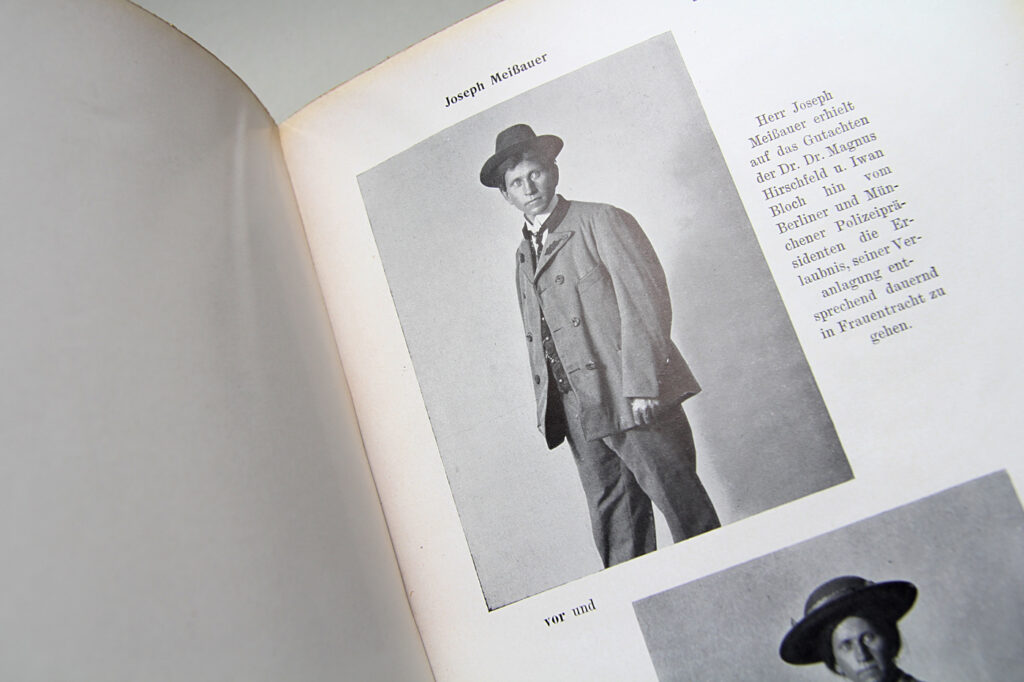

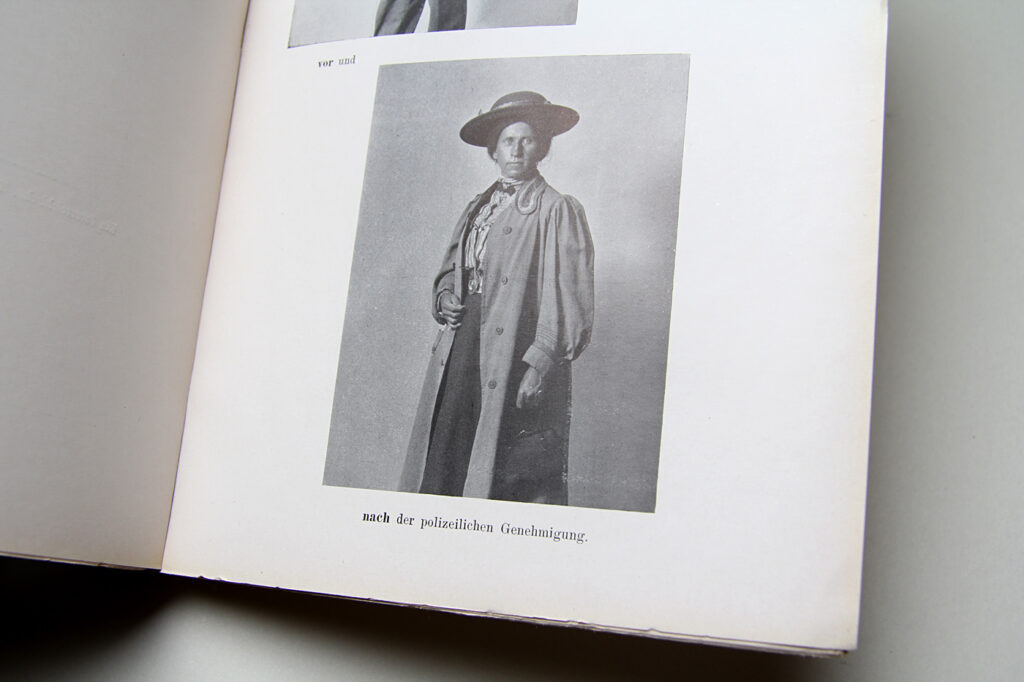

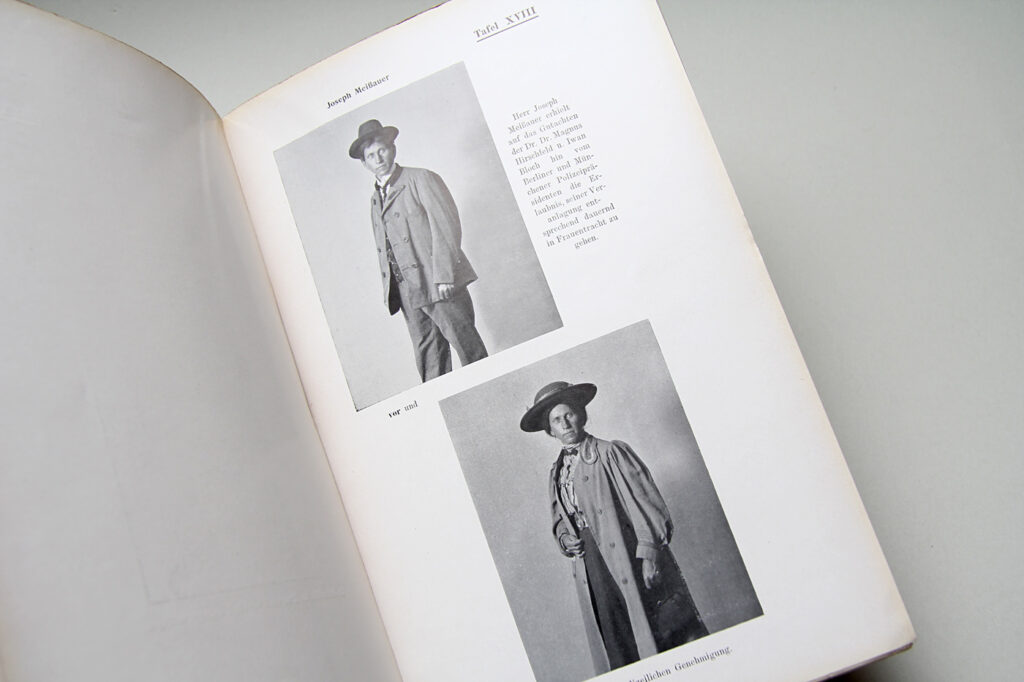

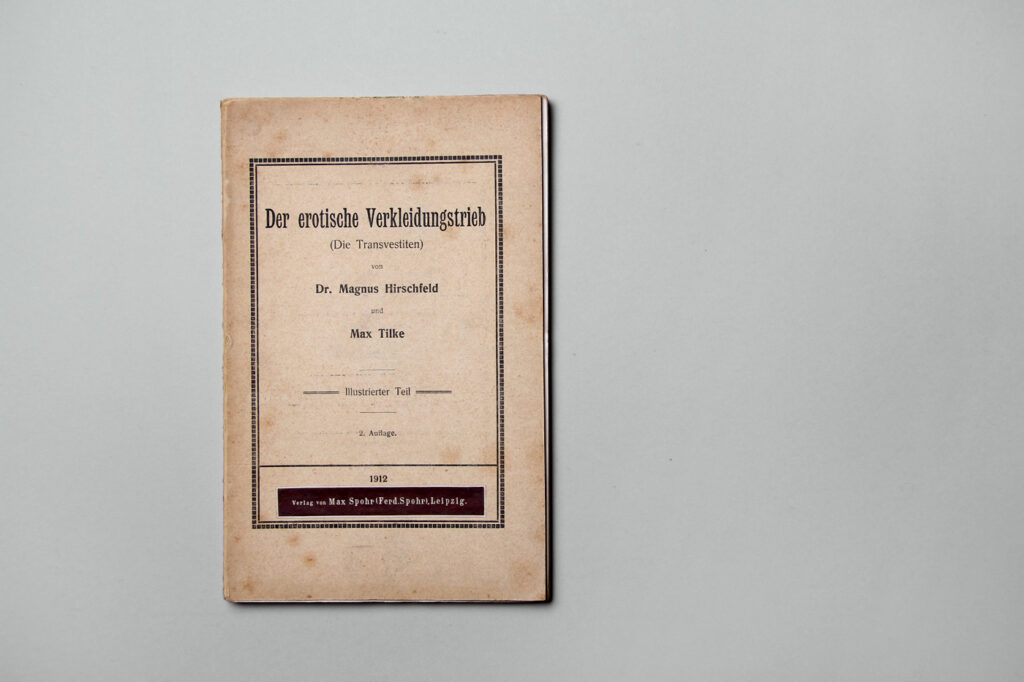

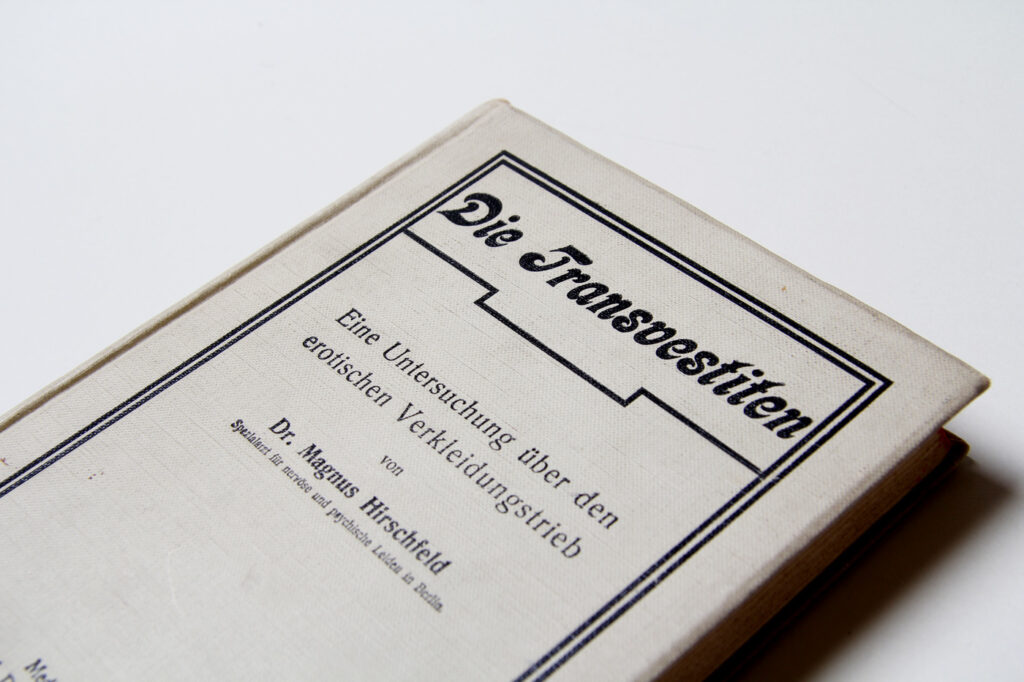

“In questions of sex, nobody tells the truth,” the German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld once quipped. But what about the transvestite? In a sense, he is showing the truth about his sexuality by disguising his sex. I wanted to use this paradox to tell a story of love and deception, of cunning and criminality, during the rise of the Third Reich.

Personally, I have no first-hand experience of transvestism. But as the child of immigrants, I believe I know a fair deal about second-degree transvestism. That is, about language. If you grow up the way I did, there’s little natural relation to words. Different tongues become different forms of dressing thought. As an immigrant child you want to speak the language of your adopted country flawlessly — you want to “pass,” as the idiom goes. That’s only one impulse, however. Another, just as distinct, is the wish to master the language of the natives just as well as or perhaps even better than they do. This creates a paradox. In a way, you’re trying to camouflage yourself as a peacock. Maybe that’s what transvestism is about?

Do you consider science a field that has yet to be approached by literature?

I’m all for the poetry of science and the precision of art. Darwin, Freud, Mary Douglas — superb storytellers; James, Nabokov, Lispector — pure clockwork of style.

Why did you choose to put subject matters that seem rather post-modern back into the period of the Weimar Republic?

Then as now, questions concerning the nature of man were being put in novel and troubling ways. There was a lot of talk about der neue Mensch, “the new human being,” that reminds you of today’s discussions of the human genome or of gender identities. Since I belong to the camp of writers who require a certain distance from their subject matter, however — after all, one needs swinging distance to be able to knock down trite commonplaces — I chose a distance of eighty years. My arms are long . . .

How did you deal with the delicate line between pornography and a decent approaching of the subject?

I wished to celebrate not the straightforwardness of pornography, but the sensuality of complexity. What’s the point of trying to compete with the TV channels after midnight? Literature is better served by relying on its innate qualities. One way to do so is to explore the confluence of voice and memory, ardor and ambiguity. Then, if one is lucky, as a reader, one may feel that thrilling tingle along one’s spine . . . That’s the biology of literature.

In what way does the scholar of you intervene in the writing process?

Do you recall the sign that Plato hung above the entrance to the Academy? “He who knows no geometry may not enter.” I fear I will never walk through those gates. It’s over fifteen years ago since I last wrote a scholarly work. I take comfort in the fact that writers have no business trying to prove things. In contrast to philosophy, literature ought not provide answers but raise questions.

© Eleutherotypia 2006