Nelly Sachs, Flight and Metamorphosis

Information · Cover · Foreword · Reviews · Links

Information

Illustrated Biography · Original title: Flykt och förvandling (2010) · In Swedish · Translation: Tomas Tranæus · Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012 · 320 pages, 350 images · Design: gewerkdesign, Berlin · ISBN: 978-0-8047-7531-1

Cover

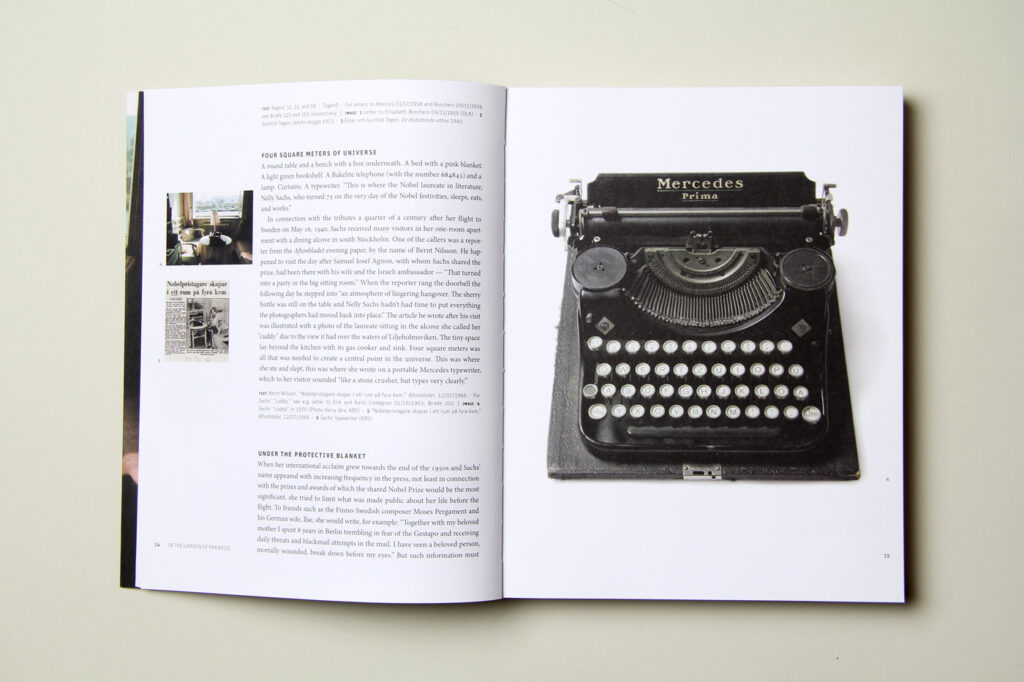

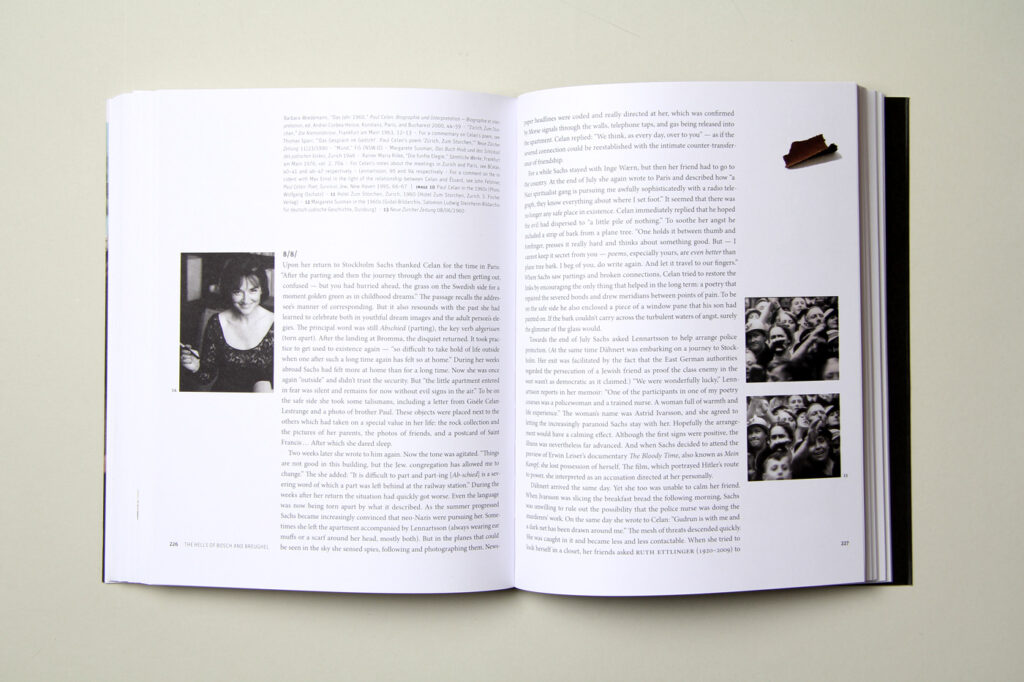

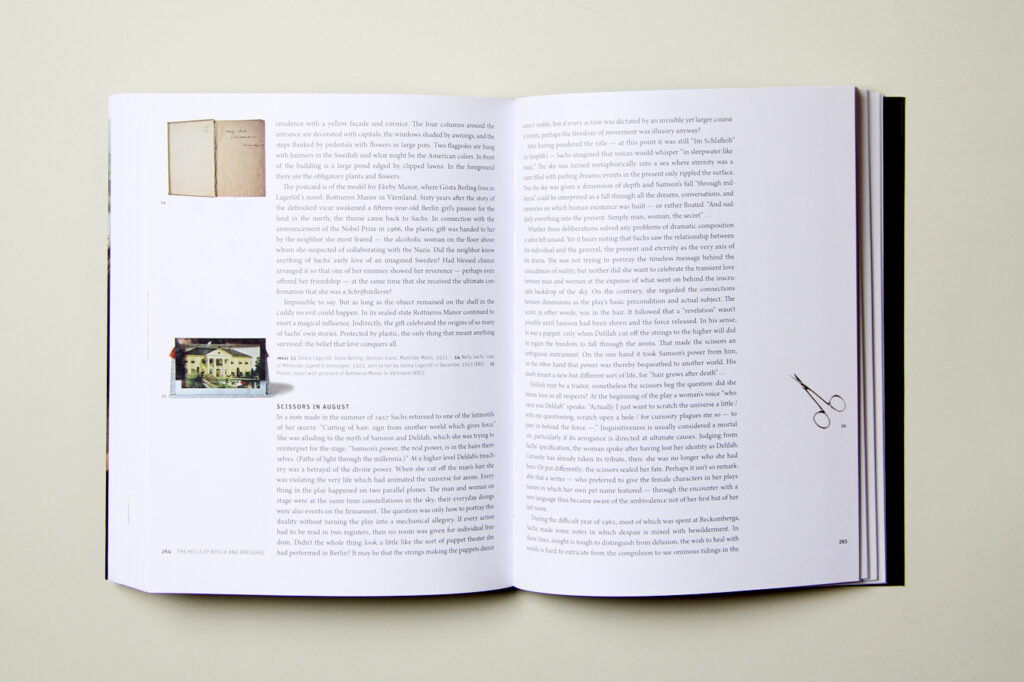

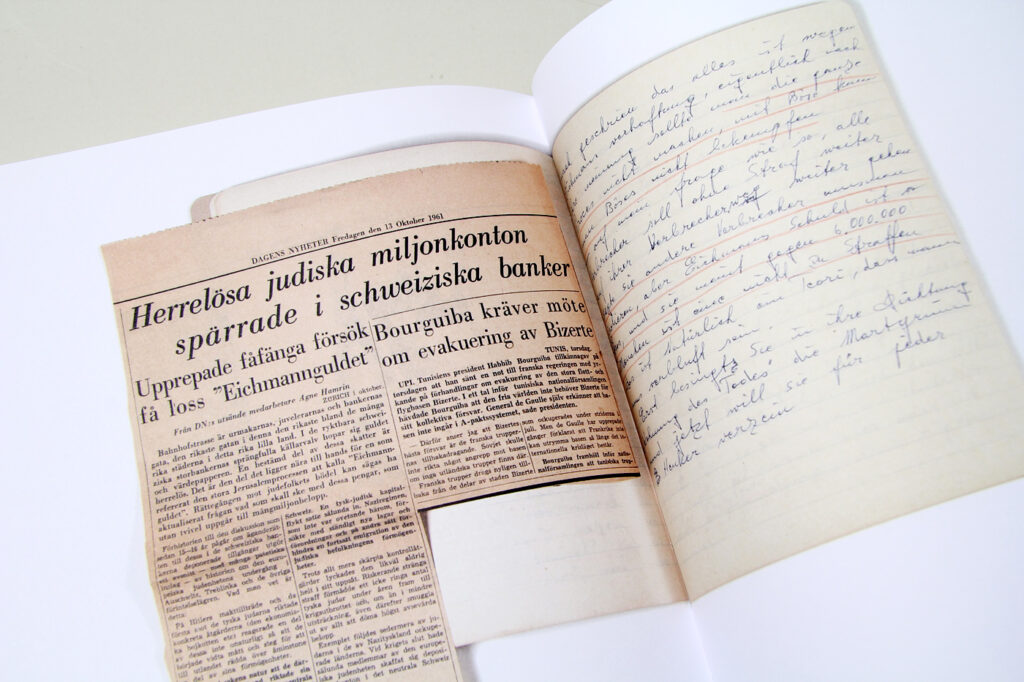

This richly illustrated biography is the first book in English to chronicle the life of Nelly Sachs (1891–1970), recipient of the 1966 Nobel Prize in Literature. The book follows Sachs from her secluded years in Berlin as the only child of assimilated German Jews, through her last-minute flight from the Nazis in 1940, to her exile in “peaceful Sweden” — a time of poverty and isolation, but also of growing fame. Enriched by over 300 images of Sachs’s manuscripts, photographs, and possessions, Nelly Sachs, Flight and Metamorphosis not only offers detailed insights into the contexts of Sachs’s formation as a writer, but also looks at themes of trauma and testimony in her central works.

Fioretos draws upon previously unknown manuscripts, documents, medical records, and photos to produce the first reliably detailed narrative of Sachs’s foundational experiences: her teenage years when she experienced the unrequited love later designated as the source for her entire œuvre; her involvement with the Jewish Cultural League—seven years marked by mounting terror but also by her first public recognition as a writer; and her exposure to the radical Modernism of Swedish poetry in the 1940s. The book further describes the years of public recognition, addresses the paranoia that marked Sachs’s final decade, and scrutinizes her close but complicated friendship with Paul Celan. An interview with Sachs’s close friend Margaretha Holmqvist provides touching insights into both her life in the 1960s and the events leading up to the Nobel Prize. Throughout, the book emphasizes the singularity of Sachs’s achievement as a writer and the exemplarity of her existential situation — as a woman, as an exile, and — as she herself said — “a battleground.”

Aris Fioretos is Professor of Aesthetics at Södertörn University in Stockholm, Sweden. The recipient of numerous prizes and fellowships, he has published several novels and book-length essays and is a translator of Paul Auster, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Vladimir Nabokov into Swedish. His latest novel is the internationally acclaimed The Last Greek (2009). Fioretos is also the general editor of the complete works of Nelly Sachs in German.

“For some years the time has been ripe for a literary biography of Nelly Sachs. Now these thorough, thoughtful, deeply studied pages, enlivened by remarkable images, should become a definitive source. Along with her close comrade Paul Celan, though not wholly like him, Sachs draws us into a molten history we forget at our peril.” — John Felstiner, author ofTranslating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew, and Can Poetry Save the Earth? A Field Guide to Nature Poems

Foreword

How to approach a writer who spoke of tragic events in her past, but avoided concrete circumstances? A writer who, in the first epitaphs to her “dead brothers and sisters,” preferred to use initials rather than full names? Who, early as well as later in life, burned poems and letters she felt were too frank, too private? In short, a writer who wished to disappear behind her work?

For Nelly Sachs, texts had to speak for themselves. No knowledge about the person behind the work was necessary; in fact, it could be threatening. Although she understood writing as an act of devotion which ultimately left no other mark than the traces of passion, her considerable correspondence — around 4,000 extant letters — shows how concerned she was that details of her private life should remain private. There are usually good reasons for respecting a writer’s wishes regarding such matters, and rarely any bad ones. Yet at the same time as Sachs withheld facts about the background to her work, she said that she was doing so. With one hand she pointed to what the other hand was hiding. This double gesture is significant. Perhaps it says something about how she viewed the interplay of life and letters.

In her correspondence with the Germanist Walter A. Berendsohn, Sachs repeatedly urged caution regarding information imparted in confidence. In order to underline the urgency of her request she used a drastic turn of phrase: if her friend were really going to write the proposed study of her life as a writer, he must understand that she wanted to be “extinguished” as a person. Sachs could hardly have been unaware that the German verb ausschalten sounded as if it came straight out of the Nazis’ vocabulary — that “diction of the Third Reich” or “lexicon of inhumanity” of which Victor Klemperer, Dolf Sternberger, and others amassed evidence after the war. Why did she use such a charged term? Was it in order to state emphatically the limits of what Berendsohn could include in his book? A demand that he concentrate on the work and leave everything else to “the reporters from the celebrity press,” as she also wrote? Or was it in fact a straightforward declaration of a more general problem: how to give expression to the defenseless without risking new exposure? Did she fear that the inclusion of biographical data would obscure the import of the poem and, paradoxically, cause more pain to be inflicted? “The heartrending tragedy of our destiny will not and must not [. . .] be diminished by the many items of information which are wholly unnecessary in this context.”

No doubt such considerations, and others, played a part. Still — “extinguished”? Despite its metaphorical proximity to the chimneys of the crematorium ovens, and despite its kinship with a verb such as gleichschalten (“equalize”), ausschalten may have suggested something else as well . . .

During the first year of their Swedish exile, Sachs and her mother lived at temporary addresses. In October 1941 they were able to move to an apartment of their own, in a building in Bergsundsstrand on the south side of Stockholm. Located on the ground floor, it consisted of one room and a kitchen, and was dark and cold. According to notes made later, it was occasionally filled with the stench of sewers. After seven years without sunlight, in August 1948, the pair were able to change to a one-room apartment measuring 41 square meters, with a kitchen and dining alcove, a couple of floors higher up in the same building. Here Sachs would spend the rest of her life. Until her mother’s death in February 1950, she devoted most of her time to caring for her. What small income she earned came from translations of Swedish literature, mostly poetry. Only at night could she write her own work — in the dark, as her mother would otherwise wake up.

This is the prototypical setting for Sachs’ poetry: alone with the alphabet at night. She felt literally “thrown into an ‘Outside,’” as she put it to the literary critic Margit Abenius. Although she may have been in a world governed by social conventions, she wasn’t part of it. Paradoxically situated, hers was an eerie sphere, bound up with the dead and the sorrow in their wake. Much later, in a letter to her French translator, Lionel Richard, Sachs would term this her “Nightly Dimension.” Ausschalten meant this, too: with the light extinguished, the person behind the work was no longer visible. Yet she was there all the same. The night was illuminated by the one thing that mattered: the writing. Whatever else there was, it should remain in the dark.

This study is devoted to the interplay between life and letters, inside and outside in a body of work neglected by critics in recent years. Hence it is also concerned with Sachs’ self-image. Her development as a poet is remarkable not least because she began the memorable part of her œuvre when she was over fifty years old. During the quarter-century that followed, her poems became ever more convincing from a critical point of view. Literary history boasts few such examples, if any. How was this development made possible?

The self-image that Sachs created from an experience of loss and parting, flight and metamorphosis was predicated on the notion that the poems came to her, that they were dictated by horrific circumstances which forced her to speak. “The words came and broke forth in me — to the edge of annihilation,” she reported in an interview on Swiss television in 1965. This image fits in with the vision of a poet with an Orphic mission. It is furthermore easy to identify traits which are traditionally perceived as feminine. Sachs is less active than passive. She does not compose poems, but rather is overwhelmed by them. She is more receiver than sender.

Sachs’ literary estate shows that she rarely rewrote or edited her texts. Many of them were printed in versions nearly identical — bar the odd word or comma — to the original. Yet must that mean she was a mere medium without intent — a handful of strings moved by the divine wind? At the same time as the circumstances following her escape from Nazi Germany were far from comfortable, she conscientiously worked in the service of poetry. She had submitted texts to newspapers and periodicals already in her youth. After her flight she contacted Swedish writers and critics and began almost immediately to translate their work into German. Despite her isolation she built, over time, a wide-ranging “network of words” with coordinates near and far, among the living and the dead, exiled writers and representatives of the younger generation. And during the difficult years of the 1960s, scarred by the effects of persecution during the Nazi years, she was periodically committed to psychiatric clinics in whose protected setting she wrote what are perhaps her most powerful works, the “glowing enigmas” and the late dramatic poetry.

This study dwells upon such contradictions and upon other ones. Even if Sachs saw herself as a “battleground,” it was in her that the words broke forth — and they did so “to the edge of annihilation.” The same convulsions with which she was born as a poet also extinguished her as a private individual. In the end the words glowed from the inside. Like enigmas, they illuminated without explanation. Thus implying that a different sort of reading was required: one that doesn’t assume the meaning of a poem is a treasure to be unearthed and exported. Inaccessibility was part of its appearance. As was obscurity.

May the following pages contain enough of the latter for Sachs’ poems to gleam as only they can.

Pages 7–9.

Reviews

“[S]achs is served well by Fioretos, whose comprehensive biography is based on material from archives, interviews and other biographies. The size of a coffee-table book, Flight and Metamorphosis draws the reader into her life and times through photographs, hand-written notes and poems, images of her typewriter, and childhood toys and drawings. Fioretos tells the story with all the suspense of a good novel.” — Zelda Gamson, Jewish Currents

“Nelly Sachs’s poems are true to Celan’s remark that ‘not to include the resistance of the incommunicable in the poem is not to write a poem at all’. Fioretos’s book and the new edition allow us to take the full measure of that resistance.” — Charlie Louth, Times Literary Supplement

“Fioretos’ elegantly written biography is the first of Sachs to appear in English . . . To its credit, Fioretos’ lucid, well-researched book never feels hagiographic, despite its abundant expressions of admiration for its subject.” — Paul Reitter, Jewish Review of Books

Links

»Flykt och förvandling,« Exhibition at the Jewish Theatre, Stockholm, 2010 (In Swedish) · Commented collected works in four volumes, Suhrkamp Verlag · »Nelly Sachs,« CD (In German)