Halva solen

(Half the Sun)

Information · Cover · Extract · Reviews · Links

Information

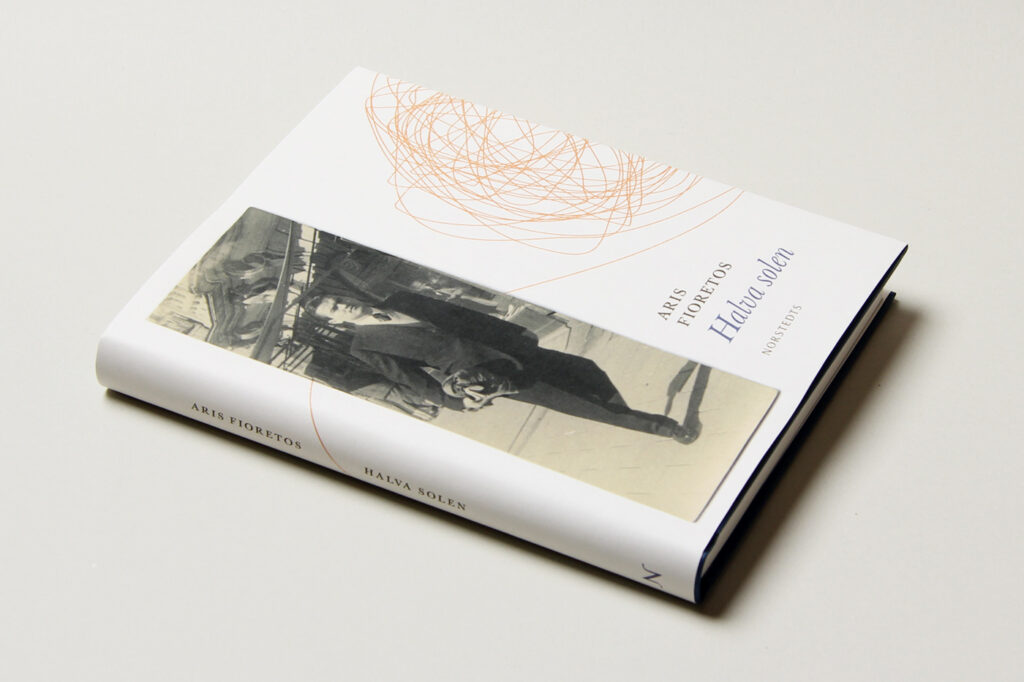

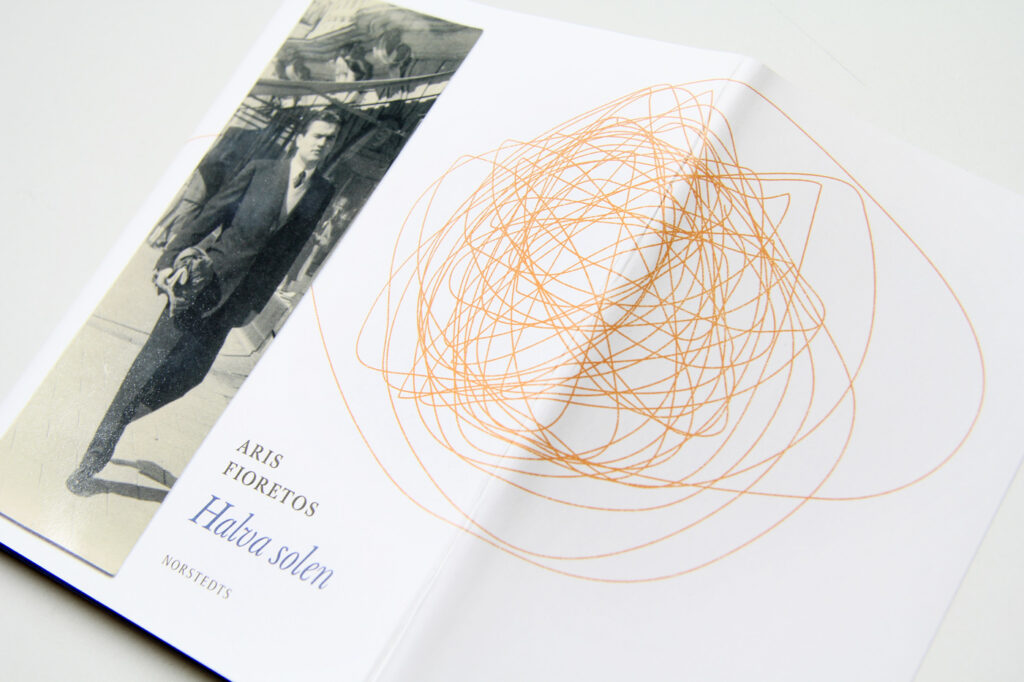

Prose · In Swedish · Stockholm: Norstedts, 2012, 224 pages · Cover: Håkan Liljemärker · Cover photo: The author’s father in Stockholm, September 1954 · ISBN: 978-91-1-304183-4

Cover

What is the definition of a father? Perhaps: he-who-protects? Perhaps: against the sun? If he no longer protects, is he still a father?

It happens all the time. A parent dies. A child mourns. But how often does this particular person die? And how does one reciprocate something of what he gave?

Aris Fioretos’ new book is both elegy and requiem in reverse. In short prose tableaux, as matter of fact as they are lyrical, Half the sun traces the adventures of an expatriate Greek — from his death in a Swedish home for the elderly, over the years in the burgeoning welfare state and back to the time before his first child. Now the father is no longer father. But has life before him.

Following the acclaimed The Last Greek (2009), which was nominated for the August Prize and received the Swedish Radio Fiction Prize, Aris Fioretos returns with the moving story of a beloved person shaped by a secret.

*

Aris Fioretos lives and works in Stockholm and Berlin. His most recent novel, Den siste greken (The Last Greek), won the Swedish Radio Fiction Prize for 2009 as well as Germany’s prestigous Literary Prize of the SWR Critics’ List for 2011.

“The Last Greek is a fabulous novel — multilayered, entertaining and poignant. Glimmering with melancholy, it is a treatise of love’s divagations, sorrows and beauty, and of the excoriating homesickness that only he who has left everything behind can feel.” — Dagens Nyheter

“Aris Fioretos’ new novel The Last Greek has . . . a magnetic force of attraction. Resolutely original and richly inventive, it is written with a tenderness and a restrained affection that will wring tears from the hardest heart. It is a very un-Swedish novel that nevertheless becomes as Swedish as — let’s see — a Dalecarlian wooden horse in Greek blues and whites.” — Helsingborgs Dagblad

“An intricate, deeply touching and sumptuous novel of love . . . as close to a masterpiece as it is possible to get.” — Upsala Nya Tidning

Extract

Second essay on hands

When dad writes he prefers block letters. The characters are firm and handsome. One day, however, I am rummaging around the basement and find a shoebox with photos from the time before houses and children. On the back of one photo have been written the name of a capital city, a month and year. The picture must have been taken during the first week in the new country, before the again-blood-cougher was interned in a sanatorium south of the city. Judging from the unusual script — S, t, k, l, m . . . — dad did not learn Latin characters as a child. I wonder if it’s the capital S with suggestion of final sigma that gives him away. Or if in fact it’s the lowercase k, h and l with their unnaturally tall loops — as if they were a special letter formed in three different ways depending on the phonetic context. Impossible to say. I only know that when dad writes, his hand also always contains another.

Solemn

I can’t get enough of the photo. There is dad, as old as I will be this summer, walking with a rolled-up trench coat and newspaper in his hand — thoughtful, inscrutable. He looks both relaxed and formal in the black suit he has inherited from his father, with a sweater, a shirt and tie, and polished shoes. But why was the image trimmed? Was there another person walking by his side? The slightly stiff left arm might suggest that. Or was the composition disturbed by other pedestrians? In that case, what’s happened to their shadows? The only other people present are a couple farther back in the image, looking at the wares in a shop, and a man in a pale overcoat whose reflection appears in a shop window.

I am overcome by a desire to accompany the twenty-four-year old, to become his shadow. This is how I want to preserve you, I murmur to dad — long before he is imaginable. Ceremoniously on his way into the future.

Pages 119–120. Translated from the Swedish by Thomas Tranæus.

Reviews

“It is . . . . a very sensuous story, full of cicadas, ripe dripping oranges and gravel roads trembling in the heat. . . . Half the Sun is a beautiful book, funny and poignant. The seemingly objective narrative quivers with a deeply felt warmth and withheld sorrow.” — Fabian Kastner, Dagens Nyheter

“He writes very beautifully and very thoughtfully. The book is made up of brief scenes of recollection but has an almost infinite depth of vision. That makes it difficult to summarise, but one’s reading is unimpeded, each story typically ending within the page. Half the Sun is a sumptuous book, glitteringly rich in ideas, emotions, sense and reflections. As all great literature it carries several worlds at the same time, several eras too, several countries and generations, but is pervaded and held together in its multifariousness by a tremendously deep love. Aris Fioretos has created a portrait of a father with classic significance, set in deepest humanism.” — Jan-Olov Nyström, Söderhamns-Kuriren

“Half the Sun is a declaration of love, a tale undoubtedly born of sorrow but whose backwards perspective makes it glimmer with joy. It is quite a luminous little book, written by a stylistic artiste who never lets his virtuosity lend a chill to life.” — Anna Lingebrandt, Helsingborgs Dagblad

“Everything is wrought with elegance and intimacy.” — Tita Nordlund-Hessler, Eskilstuna-Kuriren

“The various perspectives and many devices together shape a portrait that is fascinating not just due to the radiance of the subject but also — and perhaps more so — because of the ingenuity of the execution. The whole range of tonalities is given play: from the tender and beautiful via the lush and carefree to the wounded and tenebrous. . . . The only pity, really, is that the person at the centre of the book never had the opportunity to enjoy the vibrantly coloured mosaic his memory evoked. In that respect even the imagination is insufficient.” — Peter Viktorsson, Borås Tidning

“I could burst out ‘at last!’ — a tribute to a dead old parent amid the current flood of deeply felt reckonings. Aris Fioretos’ book Half the Sun is about the son and the dad. The expatriate Greek. The pine patriarch. . . . I like this text tremendously.” — Karin Wikars, Kulturnytt, P1

“A wonderful book!” — Malou von Sivers, Efter tio, TV4

“[Fioretos] has few rivals for the honorary title of supreme stylist. . . . The ability to imbue events with a sense of presence is also in a league of its own. The intimate narrating voice possesses a marvellous ability to do away with all distance between it and the reader. The book takes a rear-view perspective in telling of the writer’s father, always with the open question of how much we can know about another human being. . . . This is a book you never quite completely finish. It belongs among the few there is reason to pause in, live with and return to time and again. In today’s tempo-obsessed rhythm of life, books of this calibre are a rarity. It would hardly be too much to say that Half the Sun is a future classic.” — Bo-Ingvar Kollberg, Upsala Nya Tidning

“Half the Sun is a rich and abundantly generous book whose purport is realised on several levels. The love and discord between father and son lend the text a pithy psychological significance. . . . Fioretos examines ideas central to our civilisation: fatherhood, family, home, exile and the impossibility of returning. But the analysis is gratifying, and the love and light touch that define Aris Fioretos’ writing make it a veritable delight to read Half the Sun.” — Magnus Eriksson, Svenska Dagbladet

“Aris Fioretos succeeds in his rescue operation. He turns his dad into a person who is not a dad, not completely, and therefore cannot die as dad. On the contrary — in the end he is so tangibly alive that one feels his enormous hand on one’s own head.” — Tim Andersson, Arbetarebladet

“It becomes a rescue mission in which [Aris Fioretos], without ceremonial drama, descends to the nether regions — the trick to keeping the loved one alive is to take him back onto safe ground, far away from that Death which is always in the future, in that which doesn’t exist. Back to the moment when the son is born, when the dad becomes dad, irrevocably. Until fiction intervenes with its deft fingers and delivers a son just as it sends a father off to eternity.” — Bernur, howsoftthisprisonis.blogspot.com

“Aris Fioretos is a unique voice in contemporary Swedish literature. Not for him the steady epic trot. More European than Swedish, he makes high, very high demands on form and style and linguistic depth in his novels. . . . And yet: No one can make the Swedish language dance the way he does. . . . It is precisely this vitality and love of storytelling that allows one, as reader, to actually perceive a human being’s wholly unique warmth on the last page. From the words a scent of dry earth and oregano rises.” — Gunilla Kindstrand, Gefle Dagblad

“Aris Fioretos is a refreshing salt in our provincial culture. His cleverness, his cheekiness, his international perspective can bring the young Lars Gustafsson to mind. Today he publishes Half the Sun. Let me say at once that this is a brilliant book. . . . The book is a portrait of the author’s father and is characterised by a loving reverence and filial respect that don’t exclude cheek and humour. . . . Half the Sun is enormously rich, sometimes harsh as the scent of pine, sometimes hot as the merciless Greek sun. . . . [A] lament over a dead father. But one reads it with great joy.” — Åke Leijonhufvud, Sydsvenskan

“In Aris Fioretos’ Half the Sun kinship is the carrying theme. Intimacy gives the book its form, a beautiful, very sensual novel which is at once a terse personality study, essay, poem, style exercise, cultural analysis, report. For how do you put together a person when it is time to sum up? . . . . Fioretos’ tone is cool, but the novel is sensuous and easy to like. I was moved by the will to evoke a deceased parent, while on the other hand it is poignant to follow the son’s inadequacy before the dad’s expectations that he, as a Swede, grow and become a real Greek. Language and culture, the same old obstacles that make man free.” — Sven Rånlund, Göteborgs-Posten

Links

Conversation about fathers, SVT Babel, April 19, 2012 (In Swedish)