Sang froid

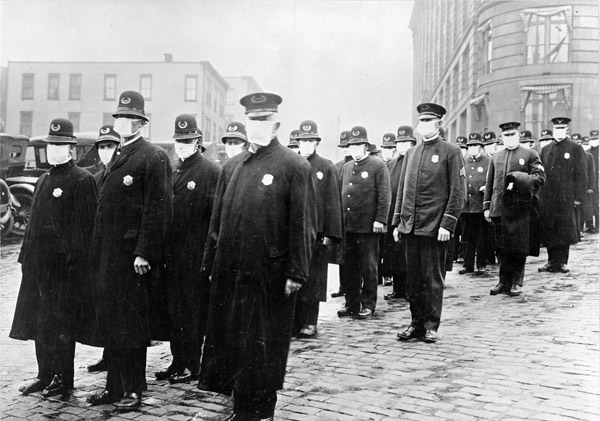

Lecture delivered at the Internationales Schriftstellertreffen, Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, on December 5, 1998 · Original title: »Sang froid« · Translated by the author · From Swedish · Ars-Interpres · 2003, No. 1, pages 142–148 · Photo: Police in Seattle in 1918

Have the temperament of a complex octopus, who

looks like whatever rock with which he is associated.

— Theogenis

“Silence, exile, and cunning,” the famous trinity of virtues recommended by Joyce, once provided viable strategies for authors. For today’s writer, however — struggling in a world where a bloated market has replaced the salôn and “glocal” has become a buzz word so boisterous that it makes silence unheard-of, exile all but impossible — only cunning seems to have survived unscathed. Allow me to offer a few reflections concerning this one unflagging virtue, perhaps in greater need today than ever before. In order to make my speculations more presentable, I shall dress them up in the garb of decidedly minor deities, among them patience, poise, and idiosyncrasy, all of which nonetheless offer aspects, I believe, of the cunning that Homer, Joyce’s distant ancestor, once termed polútropos and attributed to his hero Odysseus, the man “versatile in many ways.”

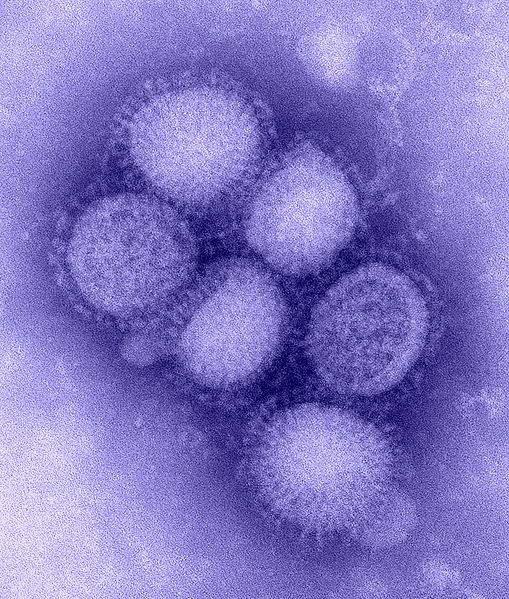

I shall begin with an anecdote. During a handful of months eighty years ago, the illness which was to become known as the Spanish flu harvested a toll of between twenty and forty million people — by far more human beings than died in the First World War. Few events, it seems to me, correspond better to what we refer to as the Zeitgeist, that intangible dash of animation so long of shadow, so short of breath. Subsequently isolated, studied, and classified, the virus h1n1 was transmitted by people who shared the same air — slept, ate, and spoke together. It visited practically every nook and cranny of the globe, rural residences and metropolitan areas alike, so quickly and conscientiously, in fact, that streetcars had to be converted into hearses and mass graves dug because of shortage of coffins.*

If the theory is correct which has been suggested by Kirsty Duncan and her colleagues at the National Tissue Repository in Bethesda, Maryland, the virus may have survived intact a few feet under ground in Longyearbyen, a village on the Norwegian island of Svalbard, some thousand odd kilometers south of the North Pole. In the local cemetery, at the foot of an ever-white hill, are buried the bodies of seven Norwegian miners, who died in early October, 1918. Cryogenically secured in the tundra, at a place where permafrost never deserts the ground, the virus might still be biding its time in dead human cell tissue. If so, thanks to modern biotechnology, the remains of the seven miners may eventually return in the guise of other-worldly emissaries, bringing us news of the most lethal strand of influenza known to mankind. At least that is the hope of Duncan and her team of researchers, who have drilled specimens from the bodies and plan to defrost the cell tissue, thus releasing the tenacious virus from its corporeal prison.

I trust today’s writers might be able to learn from this example. Not that it is part of their job description to kill readers, however few and far between they may be, but like the h1n1 virus, the literature they write must be vital enough to remain infectious. If a book is not able to get under the skin of the person who holds it in his hands, it has no business being there in the first place. To rearrange the reader’s immune defense ought to be the true calling of every work of literature. Yet in order to perform this operation, something is needed which few of today’s books — buxom bestsellers and emaciated private prints alike — can claim to possess to any great extent: patience.

For writers who, more and more, have come to see themselves in terms provided by the market, patience is a decidedly minor concern. The ills and thrills of soccer fans, ethnically-challenged life in suburbs dispersed across the Western hemisphere, slacker indifference and hacker diligence . . . in these and other cases of literary exploit, the content matter determines the text’s exchange value — or “hip factor,” to use a terminology currently more in vogue. Unusual experiential worlds may be investigated and new philosophemes scrutinized, technical vocabularies tested and modes of existential deviation persued, but more rarely do authors seem aware that without recourse to sly forms of obstruction — this confused gesture, that bewildering short circuit — little durability can be found in a world of quick kicks and instant gratification.

In a poem by John Burnside — I am thinking of the title text in his latest collection, A Normal Skin† — the pathological ID of a neighbor is described. Silently and stoically, she suffers from sensitive skin. In order to cope with existence, the neighbor distracts herself by collecting watches at “boot fairs and local fêtes,” which she takes apart at night and then arranges on the kitchen table in front of her:

She knows how things are made — that’s not the point —

what matters is the order she creates

and fixes in her mind

Dictated by personal tics and peculiarities, the idiosyncratic arrangement is the only order, I would like to venture, worth fighting for in literature. If today’s writers have a mission, it is to withstand the tides of time without taking refuge behind the dull fortifications of eternal “truths.” For this purpose, a sober mind, nimble dexterity, and no small amount of cool are needed. Because literature is, of course, not the soothing ointment with which the market still insists on confusing it, but a manner in which a person plagued by the eczema of existence may kill time. In any event, when life irritates you, poise, tenacity, and cool are in priority. The texts which then come into being provide neither salve nor salvation, and they do not heal a single wound. Yet carefully arranged into their different components — “a map of cogs and springs, laid out in rows, / invisibly numbered” — they proffer an order able to spellbind the tormented.

Burnside’s deconstructed watch suggests an image of what literature, so intimate yet always so foreign, does when it catches our attention: tacitly acknowledging everything’s deterioration, it nonetheless offers resistance to disappearance. Here, time is turned into a “map” — a representation, that is, of space — and for a few vertiginous moments pain might be transformed into the coordinates of a larger, hitherto invisible system:

What we desire in pain

is order, the impression of a life

that cannot be destroyed, only dismantled.

But even if solely the first disturbing stimulus matters for a writer — rash or rupture, rapture or ruse — only the second word will ever count. Literature is all about the search among the words written for those yet to come. Indispensable is the instinctual calculus: to pain one must respond with ordered distraction. Today, however, the faith in the salient promptings of vexation and the unwillingness to content oneself with the next-to-best phrase are given short shrift. By and large, the effort to caress a detail, to exploit an unexpected turn of phrase, or to resist the demands of genre, lack effect. All too often, texts displaying such features are considered longwinded, slow-witted, and overworked. Their idiosyncrasies are too hard to cash in, their insights impossible to pitch. In short: as products, texts of this nature have become artful, thus can no longer be consumed because of the forbidding production costs involved.

Yet when literature truly matters it is less about gain than about loss. Such is the law of every text that has been made readable, that is, unpredictable. It is part of the paradox of literature that it enriches our lives by speaking of the shortcomings. Despite this fulsome contradiction, so rich in want, literary works rarely amount to more than a keen sensibility, a handful of irritations, and a few sobering aperçues. What causes them to concern us is their ability to make such restrictions seem vital. In that sense, hardly all texts printed during these last thousand or so days of millennium no. 2 may be considered relevant, or even to being on particularly intimate terms with the Zeitgeist. At the very least, one must count as equally momentous those textures of sense and sign from earlier epochs, which still succeed in infecting us in their audacious ways. For me, a turn of phrase in Seneca, a rhyme in Marvell, a point made by Nabokov or Lispector are just as close to the heart as the texts written around me today, and not rarely more so. It has always belonged to the writer’s rights to shed the ill-fitting costumes assigned to him by critics or history. The freedom not to fulfill expectations is his only, but lasting, fortune.

As a consequence, that which makes literature “in” cannot be its willingness to be identified with its immediate surroundings in time or space, but only the patience with which it preserves idiosyncrasies over the years. “Significance” is not a perishable quality, but the manner in which we measure resistance. Mercurial leaps of thought, thrilling affect, wanton willfulness, and splendid insincerity: these are the tools available to the writer when he sets his traps, hoping to trigger his readers. There are times when literature even has to play dead. But coldheartedness, too, is a way of declaring one’s color. Mallarmé’s azur may play even across lips bitten by frost.

The only privilege of which today’s literature may boast, it seems to me, is that, like the h1n1 virus, it does not need to be new nor novel. Still, it must know how to stay alive. Literature of this cunning bent, displaying the loving vigilance of those who remain strangers in the midst of our existence, has realized that it does not have to live in the Jetzt in order to be aktuell. But regardless of whether it was written today, yesterday, or a thousand years ago, it must remain contagious. At a few feet below that pristinely white surface we find it, coolly biding its time among dead cell tissue, a skillfully applied threat that only awaits the curiosity of a reader to return to circulation. When such literature one day is discovered, caring though hardly comforting, its task is to show that it has not yet played out its role. What remains can only be patience, poise, and the explicit wish to infect us with its manner of being — or, in other words, with a term that has animated these reflections like a calm chill for far too many jittery heartbeats: sang froid.

I have attempted to describe the uses of staying cool by referring, in turn, to patience, poise, and idiosyncrasy, ordered distraction and tenacity, affect, sensibility, and splendid forms of insincerity. By my own count, these aspects amount to eight tinkling facets of the cunning once championed by Joyce. I began by invoking his distant ancestor Homer, who called Odysseus polútropos, “versatile in many ways.” In closing, permit me to return to the importance of such multivalent artifice, at times both slippery and subterranean. Perhaps you shall not be surprised to see it transformed into another, more fabled image for the versatility I have been advocating: the octopus that Theogenis, cited in my motto, once labeled “complex.”

If it strikes you as peculiar to invoke this pluripedal animal in the context of an infectiousness of literal as well as metaphorical kind, I beg you to recall the Calypso episode of The Odyssey. In Book 5 of the epic, Odysseus is indeed compared to an octopus whose resorcefulness is put to prudent test. Lost for two days and two nights in heavy seas, on the third morning, finally, Odysseus is “raised high by a groundswell” and catches an unexpected glimpse of wooded land. The surf is “exploding in fury,” however, and tremendous waves sweep him toward a dangerously “rocky coast.” Odysseus would “have been flayed alive, his bones crushed,” Homer admits, if Pallas Athena had not put it in his head to dash in and lay hold of a rock with both his hands. (When in wavering danger, embrace structure.)

Desperately clinging to that slab of rock for support, much like an anthropoid virus attached to a new cellular milieu, Odysseus is battered by furious waves. Finally, the breakers’ backwash charge “into him full fury” and hurl him back again, “out to sea.” Eventually, he manages to swim into the mouth of a riverlet issuing not far from where the angry waters persist in troubling his life, and is rescued. Just before that, however, as Odysseus is on his way out to sea again, Homer describes how

Like pebbles stuck in the suckers of some octopus

dragged from its lair — so strips of skin torn

from his clawing hands stuck to the rock face.§

Those bits and pieces of epidermal debris, thick as the pebbles that stick to the suckers of a squid, are the result, we might say, of exposure to animated tides. I would like to suggest that they also offer us an image for the characters and letters — all this alphabetical litter — that writers shed on decidedly softer, but no less fearsome surfaces, as they struggle to grasp their existence: those pristine shores we consider sheets of paper. At the very least, it would be tempting to read this human debris as an indication of just how unbearably light literature might be.

If this analogy strikes you as a mite too daring for philological comfort, it may be worth recalling that the octopus, this tempered aquatic riddle whose cunning tentacles reach far and wide and who adapts to its surroundings with such slippery grace, is the very animal, with sang so froid, in whose veins flow the cool blood we call ink.

Notes

* My account is based on Malcolm Gladwell’s report “The Dead Zone,” The New Yorker, September 29, 1997.

† London, 1997.

§ I am using Robert Fagles’s translation: The Odyssey (New York, 1996). The original is at 5:432-433. To my knowledge, Gegory Nagy was the first to connect this passage with the lines of Theognis quoted in my motto. Cf. his Pindar’s Homer (Baltimore, 1990).