The Truth about Sascha Knisch

Information · Cover · Extract · Reviews

Information

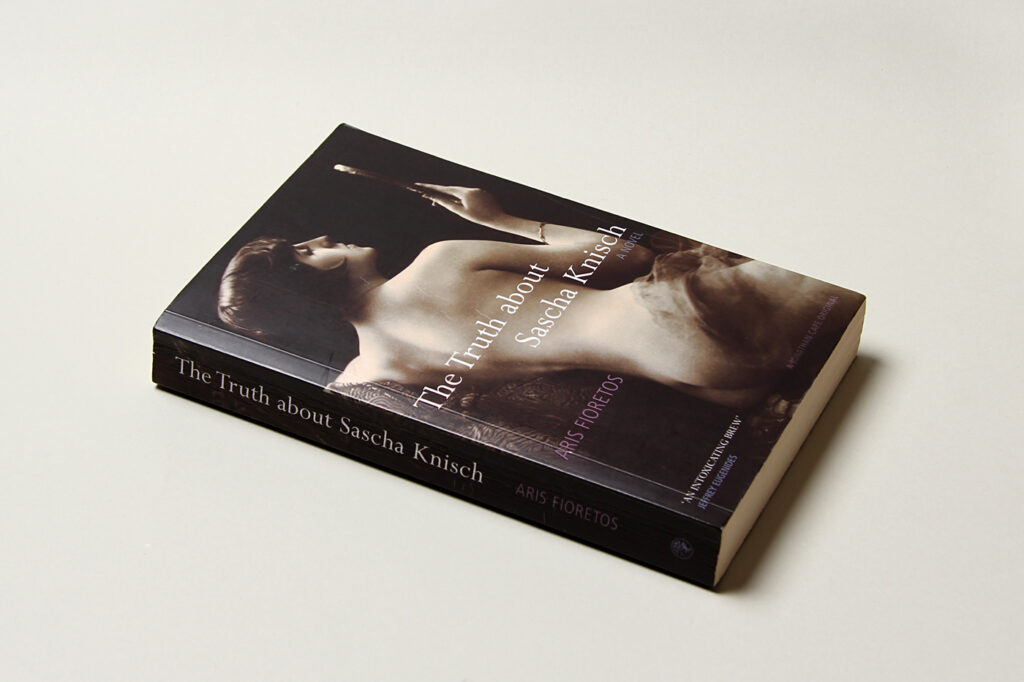

Novel · Original title: Sanningen om Sascha Knisch (2002) · In Swedish · Translated by the author · London: Jonathan Cape, 2006, 306 pages · Cover photo from the Uwe Sheid Collection · ISBN: 0-224-07685-X · Revised in Swedish in 2019 and reissued as the second volume of the trilogy Den nya människan (New Man)

Cover

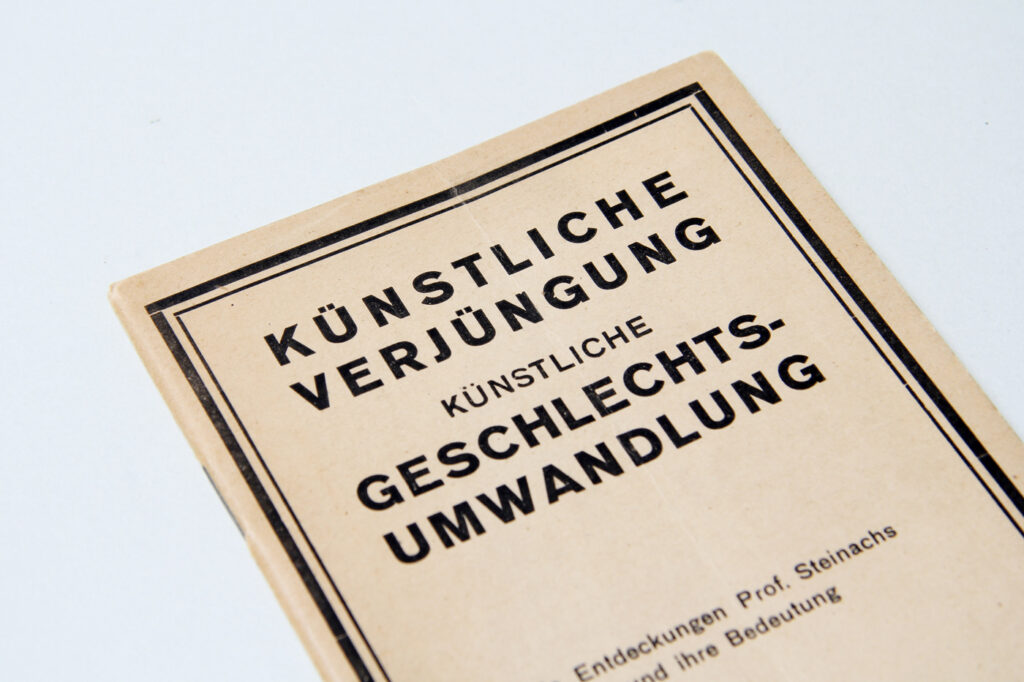

‘My name is Knisch, Sascha Knisch, and six days ago my life was in perfect order.’ So begins Aris Fioretos’s elegant, hilarious novel, set in Berlin in the sweltering summer of 1928. Knisch, who works as a projectionist at the Apollo movie theatre, is a person with special sexual habits. One night, he sees the enigmatic Dora Wilms again. A week later, she is dead and Knisch is charged with murder. As he tries to clear his name, he discovers a scientific conspiracy and is drawn into the rich tangle of a story, in which nothing is as it seems. How can he prove what didn’t happen? What goes on at the Foundation for Sexual Research? And why is it important to have testicles?

A biological thriller set in the steamy underworlds of Weimar Berlin, The Truth about Sascha Knisch deals with the so-called ‘sexual question’, its lures and seductiveness, dangers and temptations, but also with the shrewd love between two young people in a Germany at the brink of disaster. Above all, the novel is a declaration of love to imagination — clever, droll and stylish, couched in the form of a riddle and written with effortless elan by one of Europe’s most exciting and entertaining new writers.

‘Like a cunning diplomat who gets the Foreign Secretary of another country drunk at a dinner party with an eye to obtaining territorial concessions, the Swedish novelist, Aris Fioretos, in this noir-ish novel of 1928 Berlin, serves up an intoxicating brew distilled of equal parts murder mystery, sexological rumination, and historical farce. Having downed this admixture, the giddy reader is likely to redraw the borders of those warring, loving neighbors, the masculine and feminine.’ – Jeffrey Eugenides, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Middlesex

‘This incredible novel about a young man’s odyssey through the sexual underground of Weimar Germany is either a comic tragedy or a tragic comedy, and it is Aris Fioretos’ great achievement to keep you guessing past the last page. The Truth about Sascha Knisch is worldly, audacious, haunting in its candor and unremittingly disturbing in its prescience. Fioretos is without a doubt one of Europe’s most gifted writers.’ – Jane Kramer, European Correspondent of The New Yorker

Extract

Chapter One

My name is Knisch, Sascha Knisch, and six days ago my life was in perfect order. I earned a few reichsmark here, a few there, I had a place to live that could be called home, and a sex life in which nobody interfered. Certainly, sometimes I was behind with the rent, and no doubt there were moments when I wasn’t the only one to wonder when I’d get the kind of job the ads in the 8-Uhr Abendblatt describe as ‘German’ and ‘honest.’ But I’m not the complaining type. I had what I needed, and all the time I could wish for at my disposal. Now my sex is the only thing that remains — which is, of course, what puts me in this situation. The story I’m about to tell concerns the so-called ‘sexual question.’ Believe me, I’ve done what I can to avoid having to answer it. But there’s no longer any point. While I wait for Manetti — yes, that Manetti, ‘mastermind’ Manetti — to knock on the door, I had better recount what happened. And what didn’t happen. Because the truth lies in what didn’t happen, and only that can save me now.

Even if most of all this has its origin a few years back, nothing occurred until the last Friday of June. Some days earlier, Dora Wilms had suddenly appeared in the foyer at the cinema where I work extra as a projectionist — alone as always, beautiful as always, her movements full of hunger and risk. And six days ago, three days before Hindenburg’s Germany officially entered summer, I visited her. At the Apollo, she had said it would be nice to meet again ‘under different circumstances’ — adding, after a pause pregnant with suggestion, ‘your true self.’ My true self, I wondered and rubbed the palms of my hands against my trousers. Dora’s eyes were calm as deep water, but when she shot glances to the sides, as if she felt observed, I understood that she, too, could feel nervous. Presumably it was because of what had happened the last time we had met, a few months earlier. If I wanted to, she continued, fixing my eyes again, I could visit her the coming Friday. She still lived in the Otto-Ludwig-Straße, in the old flat overlooking the Stadtbahn tracks. And two days later, I cycled there in the heat of the afternoon, on asphalt soft as syrup, across the city to the part known as ‘the west.’ Not only did I arrive an hour too early, but I also misunderstood her. In no small way, either.

I should have doffed my cap and turned on my heels. But chivalry isn’t my strongest trait, and as always Dora’s face gave nothing away. Instead, I tried to make fun of my mistake. When she had spoken about meeting ‘under different circumstances,’ I had thought that, well… I made an embarrassed gesture. She understood what I meant, didn’t she? Although I felt ill at ease because of my mistake, all prick and palpitation, I have to admit I was no more than half-sincere. Truth to tell, I was delighted that Friday suddenly seemed to mean what it once had: thumping heart, hot hands, eager thoughts tripping over each other. In short: itchy, delicious nervousness.

It was on Fridays that I used to knock on the door of room 202, a couple of flights up at Hotel Kreuzer in the centre of town, on a quiet side street, with a Russian porter who always wanted help with the crossword puzzle in the paper. The person who lived there weekdays between midday and seven in the evening used neither title nor last name. The first few times we met we tried ‘Mrs.’ and ‘aunt’; I felt her first name wasn’t enough. Once, indulging a British whim, we even used ‘lady.’ However, with its soft m at the beginning and the end, long as pleasure doubled, and its two expectant a’s opening up on either side of the tongue’s erect d, the French ‘madame’ clearly was the right term. Even the silent e at the end was fitting, for it gave the word a touch of ornate Frenchness — like a frill of frozen air. ‘Madame Dora,’ then, was what I called the woman in room 202, or preferably just ‘Madame,’ for more than six months — before one thing led to another, and eventually ended in this unfortunate scene at the beginning of what the newspapers already have dubbed the ‘spectacular’ summer of 1928.

Dora waited until I had exhausted my excuses, then she stood up and suggested a suitable sum. Astonished, I looked at her. Holding her empty cigarette case between her hands, consciously or unconsciously, she had assumed the same pose as the mythical woman in red holding her mysterious box on the reproduction on the wall behind her. Having pondered the resemblance — head tilted, hands horizontal, lips softly pursed — I realised not only that she forgave me my mistake, but also that friendship made no difference. Slowly I laid the bills on the table, one after another, in the hope that she would raise her hand and stop me before I went too far. But by the time she packed away the case and asked me to follow her, I had put a month’s rent down. She paid not the slightest attention to the money. Unfortunately, we hardly had time to make ourselves comfortable in the bedroom before the doorbell rang. I looked at Dora queryingly, or perhaps pleadingly, but she just pressed the yellow blouse into my hands and said: ‘Take this and hide in here. We’ll continue in a little while.’ Then she opened the large closet and drummed her fingernails, polished and impatient, against the oak panel.

I pushed apart a couple of hangers and stepped inside. To make sure, we checked whether the door could be opened from the inside. But by now the doorbell was ringing so insistently that Dora, who didn’t deem explanations necessary, patted my cheek and said, gaze lowered and voice equivocal: ‘Be a good girl and don’t come out until I call.’ I nodded and swallowed and the lock latched shut with a compliant click. For a few confusing moments, I actually thought I could hear her looking at herself in the closet mirror. First she pulled her forefingers along her lower eyelashes, then she softly smacked her painted lips and pushed, quite unnecessarily, her newly-cut hair behind her ears. (Perhaps she didn’t possess what Filmwoche would call ‘classic’ features, but her bony appearance was oddly attractive, at least in my eyes, and her hair always perfect.) It wasn’t until I thought I could also hear the evening sun glow in her earrings, like wisps of light, that I knew imagination had got the better of me.

I stretched my neck — the high crêpe collar caused some difficulty — and strained my ears. As I couldn’t discern the click of her heels, I assumed she was walking on the wicker mat in the hallway. A few seconds later, however, I made out their sound, vague and distant, like hard, solitary raindrops. She must have reached the parquet floor in the hall. Perhaps she was looking for signs that she already had a visitor? But it was summer, whatever the calendar purported, and I had brought neither raincoat nor umbrella. Then the visitor retracted his impatient forefinger — and it was at that moment, just after Dora had turned the key in the lock, that fate began to string together its obscure threads.

If I’m speaking in veiled terms, I beg your indulgence. As so often with the sexual question, the story is improper and embarrassing — improper perhaps for many, but embarrassing for me alone — and I need a little time if the words aren’t to stick in my throat. Should the story offend all the same, I’d like to point out there’s plenty of dirtier linen that ought to be washed. Also, not all truths are naked.

Of course, last Friday I didn’t know that the threads were coming together, nor did I know that it would be the last time I’d meet Dora. We hadn’t seen each other for several months, and there I was, surrounded by her clothes, with my pulse pounding softly and plushly — as if suddenly, ripe with rapture, I existed in all parts of my body. Fate probably was the last thing I thought of. The darkness in the closet was at once narrow and infinite, and while my hands groped around, I tried to remember what Dora used to wear when we were still seeing each other. Next to me were blouses with stiff stand-up collars, flowing shark fin collars, and no collars at all. I remembered that some had pleated breasts, others had hems or bows. After the blouses came sweaters, a jumper I didn’t recognise, ditto a cardigan, and a couple of British slipovers, which, I recalled, were custard yellow with striped borders in made-up college colours. On one hanger were five or six wide silk cravats, on another a flimsy nightdress that I pulled, fingers trembling, towards my face. The soft mixture of perfume and cigarette smoke made me think of what was going to happen once the visitor had left. In a few minutes, Dora would light one of her American cigarettes, put away the case in which she kept them, and prolong the sweet agony a few moments more — smoking in one of the chairs by the window, one leg folded over the other, so that the evening sun could glide along her shin and the leather shoe, as black and glistening as motor oil. Then she’d roll the tip of the cigarette against the edge of an ashtray and slowly utter my name.

Was I holding the violet nightdress that I had once slipped over her arms, raised so matter-of-factly that I’d been able to see first the bent elbows, then the steep slope of the nose, and finally the chill-stiffened nipples outlined through the material? Or was it the shiny white negligee, usually thrown across the foot of the bed alongside the kimono in artificial silk? It was impossible to tell the colours in the dark, so instead I continued my fumbling exploration. Further in were skirts, dresses, and evening gowns of silk. Some garments hung almost down to the floor, because when I moved my hand their hems rustled with a smooth sound, almost like seaweed. Imagination aflame, it wasn’t hard to picture myself as one of a troupe of elegant dancers lined up, one after the other, waiting for the doors to be flung open so we could sail out onto the wide, shimmering parquet, where we would be met by gentlemen in tails, with pomade in their hair and cigarettes burning between sinewy fingers, next to signet rings in matted silver or mellow gold.

Suddenly, I made out muted voices, as if they were talking into pillows. Then a laugh rang out, surprisingly loud, almost provocative, and someone broke into song:

Drive, obscure, I’m in your wicked hands,

all shrewd ache and furtive glance.

It sounded like the great Rigoberto. Dora must have invited her visitor into the living room and put a record on the gramophone. Carefully I resumed my groping. Presently I came upon what could have been an old-fashioned petticoat, lined and padded, with frills of the kind my mother had also used. Then there were a few jackets, one of them from Berchtesgaden as I could tell from the typical cut, the thick seams, and the heavy material, after which followed a complicated leather ensemble, and finally Dora’s ‘Amazon outfit.’ I remembered the stylish tweed jacket over an asymmetrically cut skirt, which in turn partly covered a pair of jodhpurs. Ever so patiently, without making the hangers click or clatter, I groped until I found the skirt’s high slit and could insert my trembling fingers between the trouser legs so as to feel the leathery crotch in the glowing palm of my hand.

Slowly, however, the heat of the closet began to make me impatient. When would we finally be alone? How long would it be before she uttered my name? Dora must have been expecting a visitor. Why hadn’t she asked me to come back an hour later, as originally agreed? Cautiously I put on the blouse. Then I turned my head and laid my ear against the door, collar cutting into chin. Was that a man speaking just now? The voices seemed to be coming from the living room, because now I heard Dora say, loud and clear: ‘I hope it will pass. Perhaps we should…’ Then the door to the bedroom was pulled shut.

In the distance a Stadtbahn train went by, all rattle and routine, after which I only heard my short, scant, not particularly dignified breathing. My pulse throbbed hotly at my temples, the clothes chafed provocatively. I’ve already said that mine is an improper story, so I might as well admit that the stuffy heat, no, the stiff waiting, made me feel aroused. Without thinking, I let my hand glide down my stomach and the covered buttons, which arched softly across my midsection, like bumpy sow’s teats. The waist curved inwards and when I flexed my abdomen, the corset ribs pressed against my trunk in rigid rows. It was as if I’d become… No, this is difficult. I didn’t know that some words really areharder than others to get across one’s lips. It was as… As if I… One more time. It was as if I’d become a flower.

From the ribs down I was a moist stalk, from the chest up a glowing bud about to burst. While I imagined what I looked like, flushed and myopic, my hand continued to make its way down the ribbing and the sleek silk, towards the elastic suspenders which had been tightened and ended in metal clasps that held the stockings in place. To delay the wild, wondrous torment I felt welling up inside me like a fabulous cloud, I avoided my trembling sex and instead travelled up the other thigh, past the hip and the stiff curve of the waist, until I reached my majestic bust and burning armpit.

Racked by lust, racked by dread, I waited to hear, at long last, the creaking of the wicker chair and Dora striking a match with that fatal smoothness of hers. Calmly she would drag on the cigarette and utter my name, smoke wafting in the late afternoon sun. Again I made out voices in the hallway. Now they spoke more mutely than before. But was her visitor man or woman? Surprised, I realised it was impossible to determine the identity of a person solely on the basis of the sounds she made with her body. Finally, I decided that if they went left, back into the living room, it was a man; if they turned right, into the kitchen, a woman. Soon… Wait. The living room. Dora had male company. In that case, I wasn’t going to sneak out and sit on the bed. Not in this get-up.

Suddenly I heard a shrill shout, followed by a muffled sound, and I understood I had been wrong: they had gone into the kitchen — and thus the visitor was a woman. Had Dora called my name? I pressed my ear against the door, but couldn’t make out any further sounds. I was certain she’d call again if she needed help. Carefully I shifted my weight from one foot to the other; blood was swelling my legs. But space was scarce and every time the hangers hit each other with a ripple of titters I stopped. Slowly impatience mounted. Why did it take so long? Would the visitor really stay forever? Dora must have been reading my thoughts, for just as I stretched my toes, I heard the handle come down and the door to the bedroom open. The uninvited guest had left. We were alone at last.

I made out a dull, shuffling sort of sound and a scatter of spry steps. Odd, it sounded as if she was pulling something. Again a Stadtbahn train went by, this time with a thunderous hullabaloo that reluctantly lost itself in the distance, then Dora sat down on the bed. That much I understood because the springs in the bed moaned. After a short pause, she checked the drawer on the bedside table — probably for the extra cigarettes she used to keep there. Evidently they were elsewhere, for she rose and went over to the other side of the room. First she pulled out the drawers of the chest with muted chalk-on-blackboard shrieks, then she searched behind the curtains, and finally — wait — finally she checked behind the chair on which my clothes were. I was about to whisper through the closet doors that my Moslems were still on the table in the living room, when it struck me that perhaps she wasn’t looking for something to smoke. Rather, she might be preparing herself. Of course, that’s why she had wanted me to hide: not in order to shelter me from the unknown eyes of the visitor, as I had thought initially, but so as to prevent me from seeing, in advance, what she had planned to do once we were alone.

Dora pushed back the chair and approached the closet. Immediately, my heart pounded hard and wild, and not only the hair on my arms stood erect. But instead of saying something, she seemed to hesitate in front of the mirror doors. Perhaps she was checking her makeup? My body melted into hot, bubbly expectancy. Any moment now, Dora would utter my name. I had promised to be a good girl, so the best thing was to remain calm. Conscientiously, I pushed my legs together, straightening my back, and let the hands hang with elbows pressed to the side. Then an uncomfortable thought occurred to me: what if it wasn’t Dora who stood on the other side, but the visitor who hadn’t yet left? Were the steps I had made out not heavier, the breathing not hoarser and deep? No, no, imagination. Of course it was Dora. She’d never have let the visitor into the bedroom alone; she just wanted to test my endurance. Now I could hear her returning to the hallway — presumably to get my cigarettes from the living room. Apparently, she was out of her own. Soon she would be back, and then, at long last, it would be my turn.

But time passed and nothing happened. Gradually, silence descended on the flat. One might almost have thought somebody had passed away. Should I leave the closet and check? Or did I merely imagine things? I almost burst out laughing when I realised the simple truth: Dora had tiptoed back, shoes in hand, to see how long I’d last before I broke my promise! I clenched my fists and shut my eyes, and in this way, I managed to remain steadfast for another few minutes. But then I couldn’t take it any longer. Although the pricking agony was delicious, it suddenly felt as if my bladder was about to burst. The alarm clock on the bedside table showed 6.25 when I threw open the doors and emerged from my involuntary paradise — with the yellow blouse straining across a brassiere stuffed stiff with napkins, my hair in plaits, and my hands carefully on my hips, tottering bravely on high heels, with a red satin bow tied around my mad sex.

After that, nothing was the same again.

Pages 1–9.

Reviews

‘This is the first novel in English by this rising international lit star, and what a smashing erotic thriller it turns out to be.’ — Diane Anderson-Minshall, Curve Magazine

‘Aris Fioretos has many similarites to Vladimir Nabokov, whose works he has translated into Swedish. Like Nabokov, Fioretos has a profound knowledge of English, which is not his first language. . . . His prose style, too, is playful, attentive and deft (at one stage, in classically Nabokovian style, a man is described and dismissed in four parenthetic words — “moist forehead, nervous hands”). But the similarities are not overbearing, and Fioretos has his own voice. Most impressively, he is able to make it seem that something macabre is happening just off-camera, something that is being deliberately withheld. As a result, the reader has to keep coming up with ideas about what the next twist or payload will be; few, however, will work out the denouement in advance. There is a conflict in this novel between the dramatic and the poetic. There is the classic, noir-ish murder story and the ensuing revelations that move the narrative along. But the dense, colourful writing insists that the eye stops to admire just as it wants to return to the action. The clash is a strength rather than a weakness, since it creates an energy of its own, as the reader tries to balance the need to rush on and the urge to slow down. By the end of this involved, at times wilfully oblique, novel, the truth about Sascha Knisch may remain uncertain, but the formidable qualities of his creator have been well established.’ — Simon Baker, Times Literary Supplement

‘A stylish, intelligent and eerily entertaining novel.’ — Tom Boncza-Tomaszewski, The Independent on Sunday

‘In a world dominated by extremes, Fioretos, a Swedish-born novelist living in Berlin, presents an honest and astonishing study of the marginalized and often stigmatized people who attempt to exist between the two, specifically, those who don’t fit neatly into traditional sexual roles. . . . This extraordinary novel is destined to be much discussed and is highly recommended for public and academic libraries.’ — K. H. Cumiskey, The Library Journal (US edition)

‘When Sascha Knisch finally totters from the closet on high heels, in his yellow blouse, brassiere stuffed with napkins, his hair braided and a red satin bow tied around his rampant . . . (well, use your imagination), there is a body on the bed, and his life — previously in perfect order — will never be the same again. There is much to marvel at in this often hilarious erotic thriller set in the hot summer of 1928 in Berlin. Aris Fioretos expertly explores the camp edge of Weimar Germany, a society pressing at social and sexual boundaries but also yearning for order and preparing itself, unconsciously perhaps, for authoritarianism.’ — Matthew Lewin, The Guardian

‘[A] dense and atmospheric novel. It has all the markings of a cult favorite.’ — Publishers Weekly (US edition)

‘Sascha’s sexual needs are quite prominent in this funny, unusual novel by a sublimely gifted all-rounder. Set in cabaret country, between the wars Berlin, it’s a whodunnit seething with enough deviancy to make you not care whodidit. The tale twists and turns like an orgy at a contortionists’ convention. It’s quite funny, too; clever without being smart-arse.’ — Sunday Sports

‘. . . It’s hard to imagine a sexy, sophisticated urban thriller . . . Yet Aris Fioretos, a Swedish diplomat based in Germany, manages exactly that in The Truth about Sascha Knisch. Any fan of Isherwood or Cabaret won’t find the ambience too remote: decadent Berlin in summer 1928, as our decent hero with a little quirk (he’s a cross-dresser) finds himself caught up in a murder plot that leads not only to the pioneer sexologists of Weimar but a macho cult with far more sinister connections. Fioretos (who translates his own work, with panache) seduces with a fiendish plot and a risqué wit. . . .’ — Boyd Tonkin, The Independent

‘witty and assured’ — Christmas World Books 2006, The Independent