Grå kvartett

(Grey Quartet)

Information · Background · Remark · Excerpt · Reviews

Information

Prose poetry, essay, short stories, conversation · Stockholm: Faethon, 2024, 5 volumes · Cover image: Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff · ISBN: 978-91-89728-91-2

Background

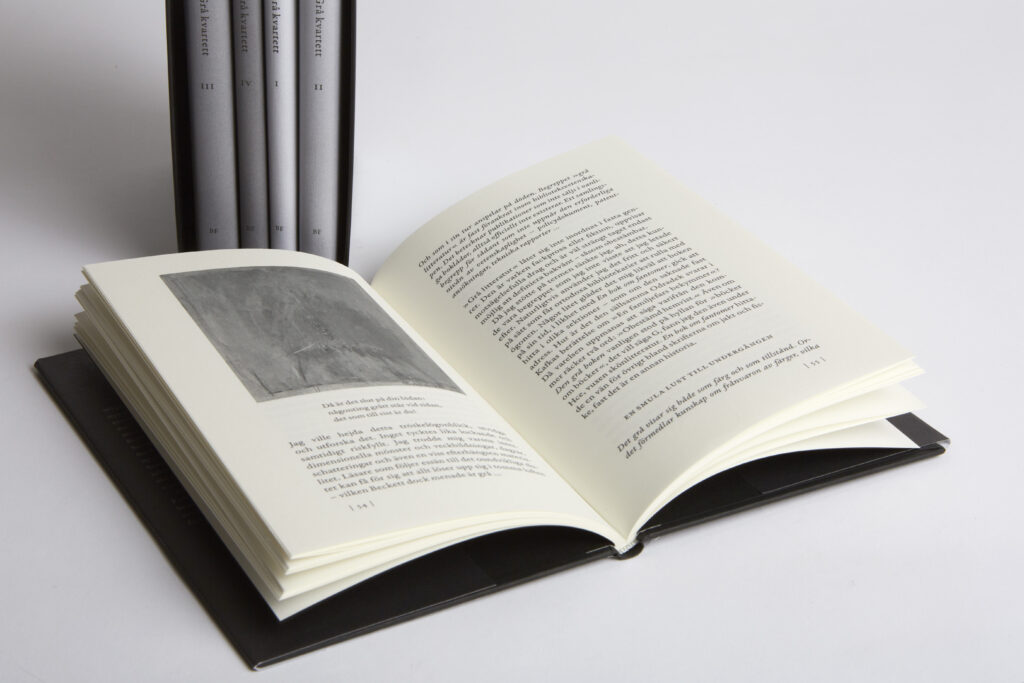

grey quartet brings together the books with which Aris Fioretos began his career. The prose-lyrical Delandets bok (The Book of Imparting, 1991) is about the grief over a girlfriend who died in a traffic accident. En bok om fantomer (A Book about Phantoms, 1996) examines the ways in which ghosts appear in film, literature and opera, philosophy and criminology, while Den grå boken (1994) (published in the US as The Gray Book in 1999) – it, too, an essay – is a eulogy to the pencil and grey areas in literature. Finally, in Vanitasrutinerna (The Vanity Routines, 1998), Fioretos lets characters as fickle as they are headstrong take their leave in seven elegiac monologues.

grey quartet is unlike anything else in contemporary literature. By examining loss and the way phantoms exist, by celebrating the sensuality of vagueness and the shifting forms of parting, Fioretos extracts continuous meaning from transience. These early books contain abundant seeds for what would later characterize his acclaimed and award-winning work. Sorrow, tenderness, wonder, ingenuity… Fioretos writes a prose both clear and surprising, and as pithy as poetry.

The four books were revised in the early 2000s. This box set is complemented by a fifth volume, Den tredje handen (The Third Hand), in which Fioretos discusses the early phases of his career with German critic and essayist Cornelia Jentzsch.

»Literature about myself? No, thank you. The self-experienced in my books is a trampoline, not a walking frame. I want to get out of my skin.«

*

Aris Fioretos, born in 1960, is the author of some twenty books (novels, essays, literary history studies). He has received numerous awards both in Sweden and abroad, most recently the Swedish Academy’s Essay Prize and the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. Since 2011 he has been a member of the Akademie der Sprache und Dichtung in Darmstadt, since 2022 also of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. In June 2024 he will give the prestigious poetics lectures in Frankfurt am Main under the title »Solar plexus«.

Remark

With the exception of the third volume in this quartet, all were revised a few years into the new millennium, when a collected edition was first planned. Only Den grå boken remained to be revised in light of the transformations the text had undergone when translated into English in 1999. The task was postponed, however, and today, a couple of decades later, I am unable to complete the labour. The revisions begun twenty years ago have been left untouched. Apart from the added quotations to The Gray Book, only minor changes have been made.

Delandets bok (The Book of Imparting) contains some allusions that are never explained; it would be futile to list them retrospectively. The original edition of En bok om fantomer (A Book about Phantoms) contained imagery by Sophie Tottie that has been omitted in the present version. Although not much has been written about grey literature (that I am aware of), a handful of studies provided inspiration during work on Den grå boken, including those by Henri Petroski and Brian Rothman – on the history of the pencil and the semiotics of zero, respectively. I should also like to mention two essays by Werner Hamacher: one on tears, the other on cloud. Finally, Vanitasrutinerna (The Vanity Routines), the youngest of the quartet, shows the least amount of change – a crossed-out word here, an adjusted sentence there.

Excerpt

Do you mean that deconstruction has reached its end point?

I would be cautious with the term »end point«. Deconstruction has shown how contradictory notions of the end are. Heralds of the apocalypse never seem to be short of work. The ideas that caused such overheating at universities in the 1980s nonetheless laid a theoretical foundation for many of the approaches and, for that matter, the ways of life that were to follow. For example, I find it difficult to believe that today’s »non-binary« thinking would be as obvious, or convincing, without Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction of dichotomies.

It didn’t take many hours in the lecture hall on rue d’Ulm before his way of reasoning resonated not only with what I was reading and thinking at the time, but also with my personal history. As the child of parents from different countries, born and raised in a third during an era that the Iron Curtain demonstrated was profoundly bipolar, I felt instinctively at home (if that’s the right word) not in one culture or another, but rather in the difference between them. I guess part of my fascination with grey areas, this desire to dwell in and probe indeterminacy, had to do with this background. I found an almost boundless pleasure in exploring the slightest nuance and shade, deviation and complication. The belief in the unstable nature of my existence, if you will, entitled me to certain pleasures.

Even today, I am less interested in confirming socio-cultural identities than in examining differences. Much of the energy that drives me comes from that. Although nowadays my writing takes on less disparate forms of expression. As a writer I have always felt a strong liberation in depicting people with different circumstances and perspectives, with experiences that I myself have not had, possibly cannot have. It satisfies me much more profoundly to learn from the experiences of others. Literature about myself? No, thank you. The self-experienced in my books is a trampoline, not a walking frame. I want to get out of my skin.

. . .

It would be strange if, as a writer, you didn’t want to change yourself, seek out new areas and perspectives, even alter your way of writing, indeed, your voice. Yet I notice a strong continuity. A novel like Mary from 2015 is about surviving as someone else. What is it you write at the beginning of the book? »This will sound strange, but I am the only one who can tell the story of how I ended.« And from what I understand, your latest novel, The Thin Gods from 2022, not yet out in German translation, depicts not only wiry, black-clad rock musicians, but also those flitting beings that many believe humans turn into after death and that we can sense, without seeing them, by our side in critical moments.

There are certainly connections between early and later works. All my books contain their fair share of pain and quirks and obsessions. Although questions of style and structure are not unimportant to the two novels you mention, neither one is about phenomena that are even secondarily linguistic in nature. Nor do I think I am trying to sniff out ghosts or hold the furies of disappearance to account. Certainly time must be stopped, at least occasionally, but what literature does not wish to accomplish that?

The acute feeling of finitude has never left me; nowadays, however, I am more concerned with creating presence – with all the means available to narrative prose. Goosebumps, blushing, joy, astonishment, despair … On the level of principle, it really doesn’t matter what the reaction is as long as the text gets under the skin of the reader. Otherwise, what good is literature? It may sound wild – or, alternatively, naïve – but I wish it to feel real. Literature is a producer of evidentiality, which possibly explains my preoccupation with the wonders and heartbreaking shortcomings of the body.

Den tredje handen (The Third Hand), pages 61–62 and 79–80.

Reviews

»For me, Aris Fioretos has always appeared to be in a class of his own, a person with access to his full capacity both socially and in writing: a little more brilliant, a little quicker, as if everyone else were running at lower revs. . . . Writing begins with cessation, with the recognition of one’s inadequacy: this cannot be said, claims Delandets bok. Writing becomes both the only way out of grief and the sole manner to maintain it, to live in a time that never existed; to remain in a place that does not exist. ›Writing‹, says Fioretos, ›became a way to hold on to the »nothing« that remained.‹ But ›nothing‹ need not be so little. In his blog The Red Hand Files, rock musician and author Nick Cave mentions a memorable meeting with fellow musician Bryan Ferry in which they discussed the fragile nature of creation: ›Deep in my heart,‹ Cave concludes, ›I know that there is always something to write about, but there is always also nothing – and not an awful lot of air in between.‹ In this small amount of air, one can take surprisingly deep breaths. Which is what happens in Grey Quartet. In the tiny breathing space that the mourner grants himself in the gap between time stopped and time passing, a pencil gradually appears, and from this grows a grey literature, a host of phantoms, an entire variety show.« – Kristoffer Leandoer, Dagens Nyheter