Den siste greken

(The Last Greek)

Information · Cover · Foreword · Reviews · Links

Information

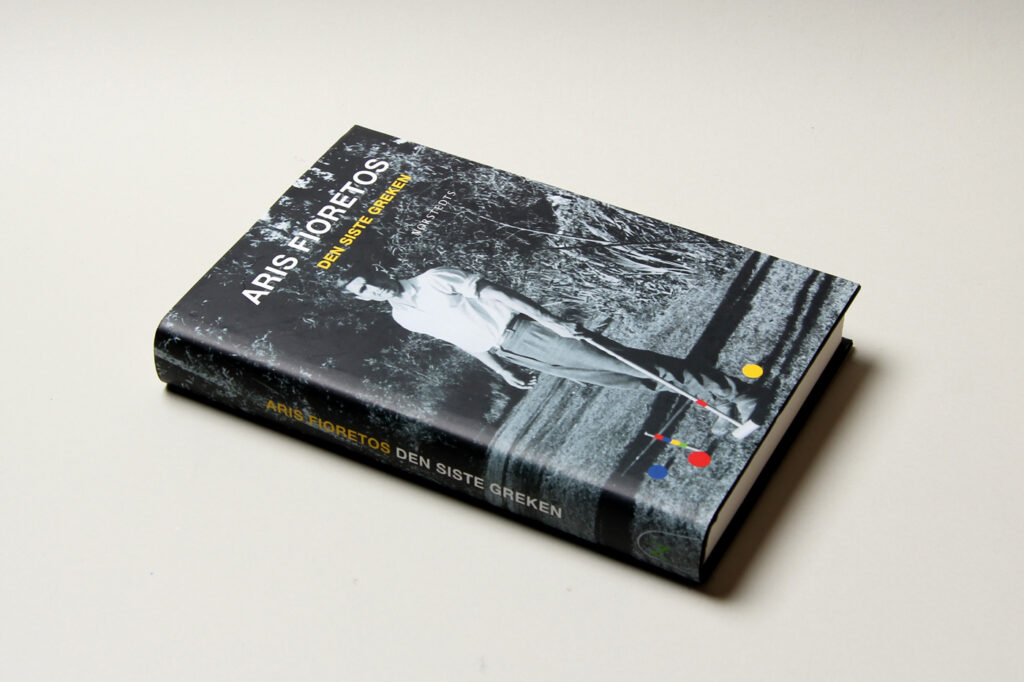

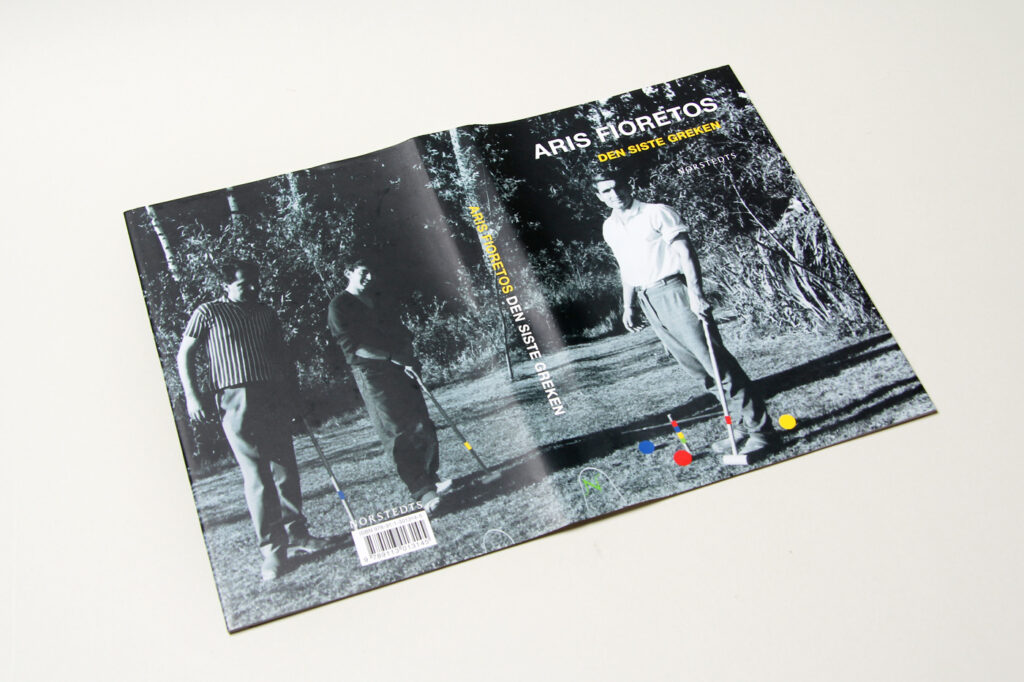

Novel · In Swedish · Stockholm: Norstedts, 2009, 385 pages · Cover: Miroslav Sokcic · Cover photo from private collection · ISBN: 978-91-1-301314-5

Cover

Meet Yannis Georgiadis – beaming, muscular and with a Robert Mitchum dimple in his chin. One winter’s day in 1967 he steps into the surgical ward in Kristianstad, and ends up staying in Sweden. We meet him as flat-footed son and dreamy shepherd, as worker, husband and father, but also as motorist on the E70 outside Zagreb one leaden afternoon in November. He plays croquet like a (demi) god and knows nearly everything about water in its various forms.

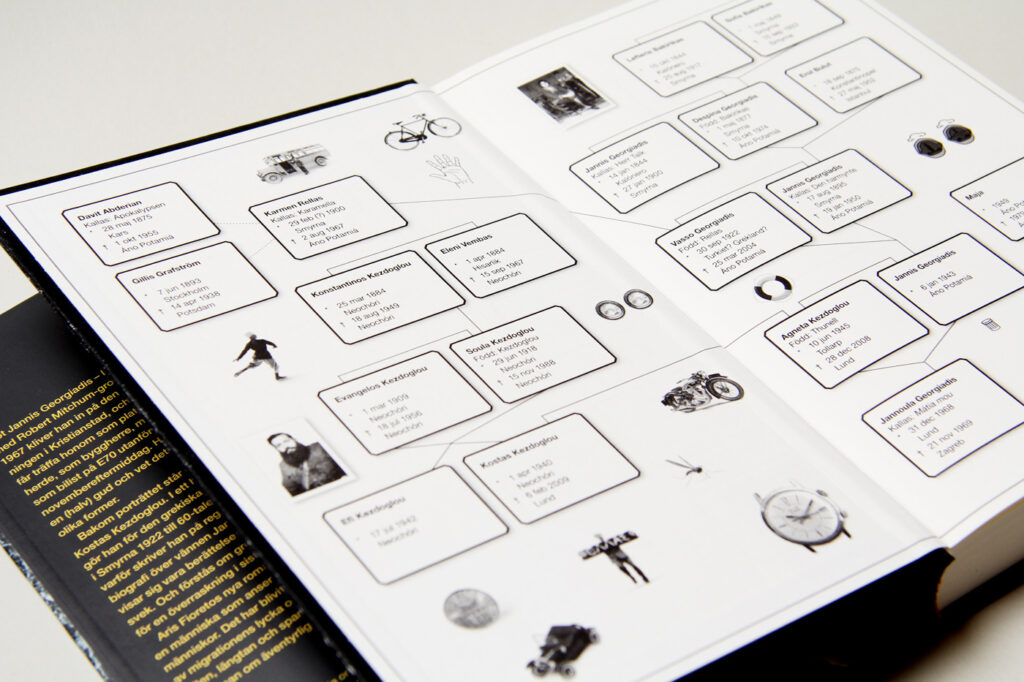

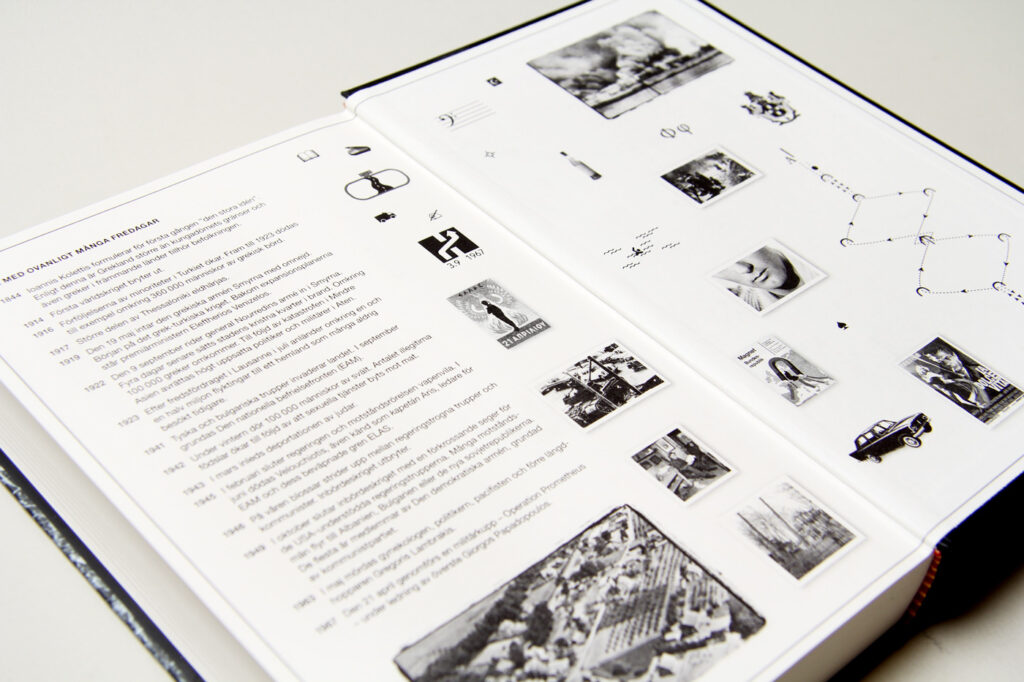

Penning the portrait is the fictitious narrator Kostas Kezdoglou. Over a hundred-odd tableaux, he describes the Greek diaspora – from the fire ravaging Smyrna in 1922 until the guest workers of the 1960s.* But why write on index cards? And why a biography of his friend Yannis? The Last Greek reveals itself to be a tale of love, friendship and betrayal. As well as of Greeks, of course, who are always “good for a surprise at the last minute” . . .

Portraying a man who believes he is made up of other people, Aris Fioretos’ new novel† is a moving account of the joys and curses of migration, of promises kept and of promises broken. In short: a novel of adventurous hearts.

* Strictly speaking it is a supplement to the legendary Encyclopaedia of Greek Exiles, published by Diaspora Press from 1928 onwards.

† Based on an untrue story.

*

Aris Fioretos made his debut in 1991 and has since written a number of books, many of which have been acclaimed internationally as well as in Sweden. His most recent title was the essay collection Vidden av en fot (“The Width of a Foot”), published in 2008. The Last Greek is his third novel, and has already been sold to other countries.

Fioretos has received many awards in Sweden and abroad, and has also translated Paul Auster, Friedrich Hölderlin and Vladimir Nabokov into Swedish. Between 2003 and 2008 he was counsellor for cultural affairs at the Swedish Embassy in Berlin. He writes regularly for Sweden’s largest daily, Dagens Nyheter.

Foreword

Kostas Kezdoglou died on the 6th of February this year at the University Hospital in Lund. A lifelong companionship with John Silver cigarettes took its toll. When his sister Efi was going through his personal effects she found a box that her brother had been given by his wife at about the same time as this book will end. It was of untreated pine, twenty centimetres wide and twenty-five deep, with a height of half that. Stuck to it was a Post-It note with my name and number, urging me to do what I thought “best for the contents”. A few days later I opened the lid and found hundreds of tightly packed yellow index cards. The top line was red with a hint of purple, like a crease in the palm of your hand, the other thirteen as pale grey as the inside of the sky. Some were covered in scrawled notes, others almost empty. When one card had not been enough for a subject, the author had used several, so there were many packs held together by a paper clip or a rubber band. The top card usually had a title, which made searching easier. It took a few minutes to get accustomed to the handwriting, then it became evident that Kezdoglou had dedicated his final forty days to incomplete actions in the past.

Following conversations with Efi it was decided that I should do what I could to get the manuscript published. As far as we were able to tell her brother had regarded it as finished. I have corrected mistakes typical of immigrant Greeks, but left peculiarities of style alone. Similarly, the order in which the cards were found has been left untouched, even if the temptation has been strong to sort them out and make the account more linear. I suppose Kezdoglou wanted to show that chronologies are relative. The material was edited in his old study, where these lines are also being written on what would have been his birthday. My publication of the text is nevertheless accompanied by a few doubts, which I wish to describe in what follows. First, though, the background must be outlined. Otherwise Kezdoglou’s stab at “non-fiction” risks coming across as odder than it is.

It is 1922. In Smyrna, there is the sound of shouting and shattered glass, of bolting horses and something that could be a thunder machine but isn’t. Since the author is about to describe what happened when the Greek minority was expelled by Atatürk’s troops, I don’t wish to anticipate events. But I must mention that his grandmother was forced out on one of the death marches. Eleni, who was going to be thirty-eight that autumn, walked with the Greeks and animals who poured in columns out of the mad city. Many perished, others disappeared. Towards the end of that year she managed to get a passage to Cyprus. She wore an embroidered winter coat to protect her from the fresh gale, and under her arm she held a bundle containing photographs, a crumbling lipstick and the homemade rear view mirror from the family’s Austin Seven. She was brave, she was inconsolable, she had just lost a husband and two of her three children.

After a few months in the city the Greeks called Ammóchostos and others Famagusta, Eleni boarded a freighter destined for Thessaloniki. In the years that followed she felt like a spider without legs. Her thoughts were wholly occupied with those she had lost, she was sick with bereavement. Later she would meet a widower with children of his own, and form a new family. But during this first period the mere thought of a new existence seemed like a betrayal. “Phantom pain”, she used to say to those who could bear to listen, “I am made of nothing but that wretched thing.” It wasn’t until the widower – a postman from a mountain village – visited the central post office where she’d found employment that a change could be seen. And following events better described by others she began to write down memories of a world made foreign.

With time the piles of old envelopes and telegrams on which she wrote grew higher. When she recalled former acquaintances she needed to know who the parents had been, which led to questions about where the family was from, to events, secrets and to blurred, almost invisible imprints on history. Realising that no man is an island, no event isolated, was a source of both hope and despair. Despite feeling pleased with her progress, Eleni recognised that she wasn’t capable on her own of salvaging the memory of all her lost compatriots. After the flight, women friends of hers had settled in Patras and Piraeus, but also in such distant places as Fulda, Toronto and Melbourne. She made inquiries, and several of them offered help. One tip led to another, one clue to the next, and in just a few months the group of twelve women created a miniature world replete with alleys, boulevards and squares. Scaffolding could be seen here and there, and one dimension or other was missing in several places, but the women would not be discouraged. During a summer with grapes the size of chestnuts, Eleni reworked the letter responses into encyclopaedia entries of which she then made twelve copies. In time for the tobacco harvest, she had them bound at a seamstress’s in a neighbouring village, and as the peasants were burning the fields, she sent the books off to the four corners of the globe. This was to become the first volume of The Encyclopaedia of Greek exiles, “published” in Neochóri in the late autumn of 1928.

When her friends pored over her efforts they discovered there were several characters still waiting to be given a name and a face. More troubling was that Eleni hadn’t separated tales from truths. The women certainly realised that the dream of a recreated community, complete with everything from confidences and love affairs to muezzins and circus artists, would remain just that: a dream world. But this was not because they lacked dedication or patience, it was because the task itself was impossible. The unwillingness to discard any recollection, even those without support in a collective past, threatened to break up the enterprise from within. If the colleague didn’t draw a line in time, didn’t distinguish between rumour and fact and didn’t check witnesses’ accounts, the world would eventually take on such peculiar proportions that it would require more than an Atlas to bear it. Moreover, no-one could be sure that what was being created was a temple and not a rubbish heap. After some animated correspondence in 1929-30, the women agreed on “a whole new ball game”, as Athanassia Osborn of Astoria, New York, put it with newly-acquired American directness.

Four years later the first volume was republished, half as thick as the original but twice as reliable. From having collected wishes and whims that only concerned Greeks from Smyrna, the friends shifted to focusing on facts about all sorts of compatriots in the diaspora. After all, Smyrnaean was only one of many ways to be a Greek. The main problem was not the broad avenues through history, with their myriad cross-streets and blind alleys, but the hopes that travelled them. “Every Greek”, we read in Osborn’s revised preface (you can hear the budding ethnologist), “constitutes a complication of what is Greek. We are not driven by some great idea, but by a small hope: that the exception proves the compatriot. Anything else would be a disaster, of which we have seen enough examples during this short, grey century.”

The sacrifices during this later phase of the work were considerable, but they were borne with equanimity. The women, now calling themselves “Clio’s aides”, sensed that if they were only diligent enough, the gallery would become so rich and varied that their place among historiographers would be assured. Herod, Xenophon, Strabo … The Encyclopaedia would do what no-one had managed to accomplish in three thousand years of Greek history: give a home to the brothers and sisters of the diaspora. Patiently they examined the rumours and recollections that make up a person in another person’s thoughts. Wild guesses and euphemisms were eliminated until only facts verified by independent sources remained. “Poetry has always been a poison for Greeks”, Dr. Osborn pointed out when she rejected an unverified statement. “Let us rather include too little than too much.” The material had to be secured while it was still “alive”, because when people died for other reasons than being Greek there was the risk that it would be impossible to confirm the memories, no matter how beautiful or painful. Still, no entry could be published until its subject had passed away, for a Greek was “good for a surprise even at the last minute”. When the material had been gathered, a typist would be employed to produce a clean manuscript, and at regular intervals, when enough dollars or dinars had been raised, a new volume would be published by Diaspora Press.

Perhaps there are readers who have come across these thread-bound, soft-covered publications. If so, they will know that the aides struggled against obstacles: fires, wars, tuberculosis, poetry, old age, dictatorships … And a few other things as well – such as lead of different kinds, including the types used to set their books. The postman died when the seventh volume had gone to the printers. A hiatus followed, since the double widow didn’t know what to grieve more: the country she had been forced to leave or the collapsing bridge to the new one. Her friends wrote urgent letters, all of them in vain, and after a few years continued on their own. The grandchildren would remember how their yiayiá sat at her writing desk in the afternoons, distractedly stroking her winter coat, unsure of whether she had survived time or time her. Sometimes Kostas – named after his maternal grandfather, and the author of the pages that follow – would visit her, particularly when he became older and felt tormented by the low demands made on him at school. Then Eleni, who was only his step-grandmother, would take him with her to a past she claimed belonged to him as much as to her. She’d tell him about sorrows and confusion, she’d describe jubilation and awe, and she’d ask whether a Greek ever got rid of That Wretched Thing. When her grandchild later left the country she eventually resumed her work. Shortly thereafter she died.

I have dwelt at such length on this background because I believe it says something about Kezdoglou’s supplement. After his wife, Agneta, died of breast cancer on the 28th of December last year, he must have felt his own time running out. It may be that he doesn’t describe a whole life. Yet his box contains a unique fate, captured in the course of a few but formative events that extend across several generations. The fact that he is describing another person need not, however, mean that he is any less partial. I, for one, find it difficult to avoid the impression that he is using the portrait as a mirror for himself, despite the historian’s first rule about maintaining an appropriate distance to his subject.

Kezdoglou seems to have adopted his hero’s view: people are made up of other people. The only way to do them justice is to accept a material situation by no means limited to a sheath of skin, bones and some internal organs, among them the heart which in Kezdoglou’s case would suffer a fatal stroke. The intention arouses sympathy but also inspires doubt. Why doesn’t he own up to the poetic freedoms? Why does he allow the biography to drift between substance and speculation without saying which is which? Sometimes he claims that the account is based on press cuttings or personal interviews. Yet he hides his sources behind pseudonyms and treats observations which cannot be attributed as if they were concessions to the human need for local colour. Other times he lets the story lean against a wall of loose assumptions. Direct speech can only be taken with a pinch of salt, and his habit of referring to himself in the third person – most likely in order to echo the encyclopaedia’s neutral tone – doesn’t in itself remove the personal interpretation. The arrangement with index cards even suggests that Kezdoglou has sought to create a novel-like plot, probably out of displeasure with the cold rations of life: facts. For how else are we to read the references to figure skating and croquet, to mention only a couple of activities from which the main character derived an uncomplicated joy, but whose loose ends are wound into a thread that the book would have us believe bears the same colour as the creases in the palm of your hand?

It is nice that the author takes us along to some of the sites of delight and distress encountered in life. It is nice that he introduces places and people, both imaginary and in Macedonia, which are otherwise easily forgotten. But for anyone who reads the book closely, for anyone who wants to use it to understand a 20th century fate a bit better, the account appears annoyingly evasive – prolix in situations where an adjective would suffice, mute when a dictionary would be called for. I have a feeling that Kezdoglou has been plagued by a seriously bad conscience. The question is why. And the question is why, despite the events that preceded the printing in 1969 of what would be the last volume – when an unexpected discovery was made and a book-burning was improvised in a back yard in southern Sweden –, why he despite the “Lund incident” as it came to be known in hand-picked circles, chose to return to the scene of his defeat. (Obviously, I’m talking about literature with a capital L.) Having edited the material, I can only think of one answer: he is seeking redress. The reader must decide on whose behalf.

When, for the last time, I let my fingers wander over the cards, from the prehistoric 19th century with its sooty niches to the light-filled and practical living rooms of today, it is this unreliability that stands out. Oddly enough it fills me with tenderness – for the ice hockey players of Tollarps IK with their oversized jerseys and gobs of snuff-stained spit, for the boys who visited the main character in the room next to the oil-fired boiler, for their mother with the perfect coiffure and the sweetly-scented armpits, and naturally for her husband who when he saw tanks rolling through the streets of Athens exclaimed: “This is the blackest Friday in the history of the month of April” – yes, for every 1/1, 1/2 etc. Greek in the places where the following scenes are played out, but also for the mosquitoes, fridges and pillow cases of the past, for its goats, matches and ten-drachma coins, for the “fair baker’s daughter” who a hundred years ago, making a deaf lover sad, did history a favour, as well as for the gentleman who a couple of centuries earlier put his shandy down and invented croquet. As well as for this mystery with pomaded hair, of course: “Yannis Georgiades”. For that is the name of the hero in the box.

But now I am starting to sound like Kezdoglou. May he rest in peace. Just a couple of more things. I am probably the “Anton Florinos” (*1960) mentioned here and there. When I first received the index cards, however, I wasn’t sure whether this was a being with skin and skeleton. To be honest I still don’t know what to think. But the uncertainty bothers me less at this point. As “Yannis” said when I reached him on his mobile phone and he explained that he did not wish to peruse the material: it is every person’s own affair how he or she prefers to remember others. Is it not self-evident that the recollections move like textiles draping a body which is nowhere fixed? Water bound in changeable forms: possibly no-one is much more than that.

On one occasion the subject under discussion is named “the Swedish Hercules”. That would be a fine title for a book, but not this one. Also, I wonder what Clio’s aides would have said had they heard that he is still alive while the biographer is dead. As I now replace the lid once and for all, it is difficult not to recall a few lines quoted by Kezdoglou: “A stranger at home, a stranger away, / A stranger yet, here in paradise.” Are the words perhaps more apt for the author as he lies there in his wooden box of quite different dimensions? Another line from the same work springs to mind: “Come, though too late, my gentle hero’s epic”…

Aris Fioretos

Sparta, 2009

Pages 5–12. Translation by Tomas Tranæus.

Reviews

“Aris Fioretos’ major new novel Den siste greken [The Last Greek] spans several countries and generations. Smyrna 1922, Macedonia 1943, Sweden 1967 … Capturing the joys and curses of the immigrant worker, his portrait of Yannis Georgiades is att once playful and enchanting, with an extravagance of bitter-sweet events.” — August Prize Nomination citation

“You can only praise this novel: as much for its wit and sophistication, as for the riches of realities that it offers its reader.” — Christoph Bartmann, Literaturen

“Fioretosʼs language belongs to the most beautiful one may read in Swedish: often it is so musical and beautiful that, as a reader, you can only feel the greatest gratitude towards this baffling mastodont work of art” — bernur.blogg.se

“It is a great moment when literature and love merge and become one.” — Helmut Böttiger, Die Zeit

“The Last Greek is full of at once sorrow and hope, but above else gripping — yes, heart wrenching — in its tender melancholy.” — Crister Enander, Helsingborgs Dagblad

“Aris Fioretos has written a virtuoso and gripping novel.” — Carsten Hueck, Radiofeuilleton Kritik, Deutschlandradio Kultur

“Let me say immediately that The Last Greek is a fantastic novel, multilayered, entertaining, and gripping. A bittersweetly shimmering treatise on the errant ways of love, sorrows, and beauty, as well as on the shafing longing that only he can experience who has left everything behind.” — Eva Johansson, Dagens Nyheter

“ʻEach person must decide for herself how she wishes to remember others,ʼ Yannis believes. Aris Fioretos, too, has decided. It has resulted in a surprising, exhilarating, and wise novel with a tad of madness, which you want to reread as soon as you have reached the end.” — Sandra Kegel, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

“To the extent that this has not previously been made clear: we have here a new and important writer knocking on the door to the Swedish Helicon and demanding access. Swedish literature is to be congratulated on the breakthrough of Aris Fioretos with The Last Greek, which is as close to being a masterpiece as it gets.” — Bo-Ingvar Kollberg, Upsala Nya Tidning

“I very much like this wonderful novel. I am utterly delighted. . . . It is a very, very beautiful novel, a sensuous novel which has the marvelous idea that everything is layered within us and that time does not run straight through our bodies.” — Felicitas von Lovenberg, Literatur im Foyer, SWR Fernsehen

“[The Last Greek] is a grand, if fragmented family novel, a fantastic and unique life story.” — Sigrid Löffler, Kulturradio, Radio Berlin-Brandenburg

“Genial . . . a migration novel in the purest sense of the genre.” — Ursula März, Buch der Woche, Deutschlandfunk

“The Last Greek is superb entertainment. But above all it is a powerful novel about belonging in the world. It may be based on an untrue story, but it rings anything but untrue.” — Karin Nykvist, Sydsvenska Dagbladet

”[DenThe Last Greek] is just as emotionally gripping as Gone with the Wind, but it so beautifully sophisticated and daringly construed in its narration that you can only admire its brilliant intelligence.” — Denis Scheck, Druckfrisch, ARD

“Imagine a wild mix of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Thomas Pynchon.” — Daniel Schreber, Cicero

“[An] impressive novel” — Andreas Schäfer, Tagesspiegel

“The style is cool. The story like a steaming, teeming multitude. Writing becomes mastering the discipline of the passions. As I read, I struggle to maintain a distance. Is it really good? But afterwards, as I look through my notes, the whole novel pours over me again like an avalanche. All those strange characters. All those peculiar side events. The big politics. Europe. The pain that must be controlled. I’ve been deeply moved without noticing it.” — Per Wirtén, Expressen

“The Last Greek is like a wonderful Rubrikʼs cube, but made of words and history.” — Rebecka Åhlund, Borås Tidning

“Aris Fioretosʼs new book The Last Greek is a tight novel, full of stories, insights, nostalgia, and history. It takes a long time to read, and is incessantly suspenseful. . . . At times I I am depleted and must put the book aside for a moment. But having finished it, I realize The Last Greek belongs to the novel I will read again. It is instructive and memorable. And there are love scenes that are unbelievably beautiful.” — Kajsa Öberg Lindsten, Göteborgs-Posten

Links

Conversation with Denis Scheck about the book, Druckfrisch, January 30, 2011 (In German) · Conversation with Franziska Hirsbrunner about the book, 52 Beste Bücher, March 7, 2011 (In German)