Solar plexus

(Solar Plexus)

Information · Cover · Contents · Foreword · Reviews · Links

Information

Reflections on a Writer and His Body · Stockholm: Norstedts, 2025, 156 pages · Design: Atelier Sofia Sorteri, Berlin · ISBN: 978-91-1-313856-5

Cover

In three personal reflections, Aris Fioretos tries to understand how the strong sensation of presence that a body immersed in water might be transformed into literature. He speaks of urge as the condition of texts, examines hunger as a demanding experience, and investigates electricity – tremors, quivering – as a way of being both in and outside oneself.

With clarity of thought and empathy, Fioretos meditates on the anatomical secrets of literature. What makes a text urgent, subtle, concise? Is it possible, as a writer, to disturb the universe without measuring oneself against gods? And how to make words feel like flesh does?

Solar Plexus is an equally lively and original defence of a literature that feels real.

»I thought with the greatest gratitude that as long as there are bathtubs, it is worth living. A bath and a cigarette.«

*

Aris Fioretos is a writer. He lives and works in Stockholm and Greece.

Contents

Foreword 7

I. Urge 11

II. Hunger 53

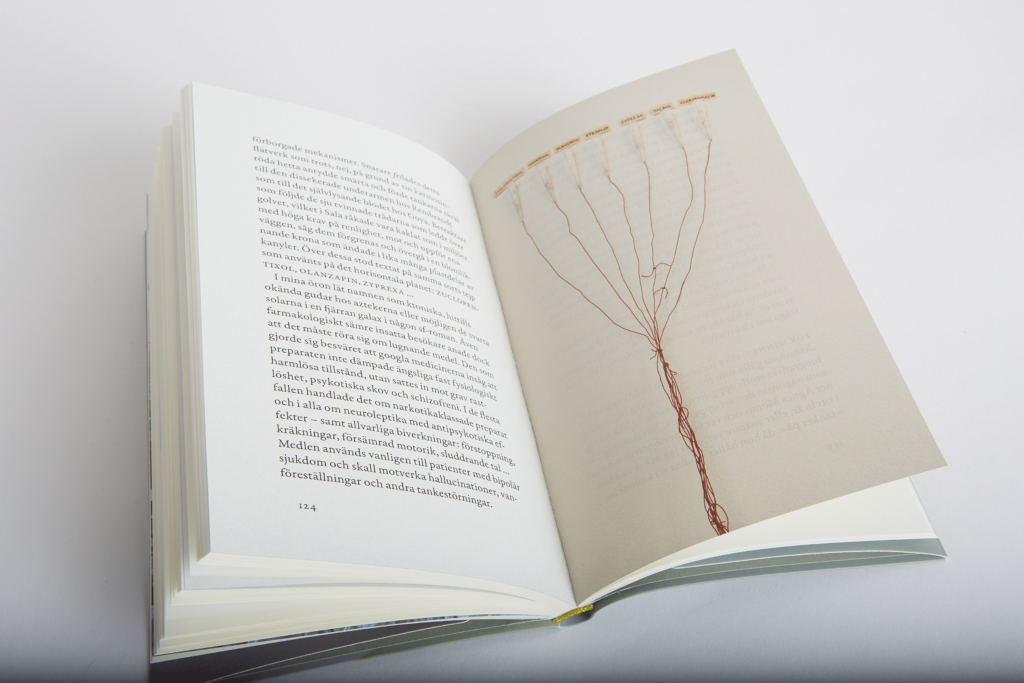

III. Electricity 93

Coda 136

images 150

note 152

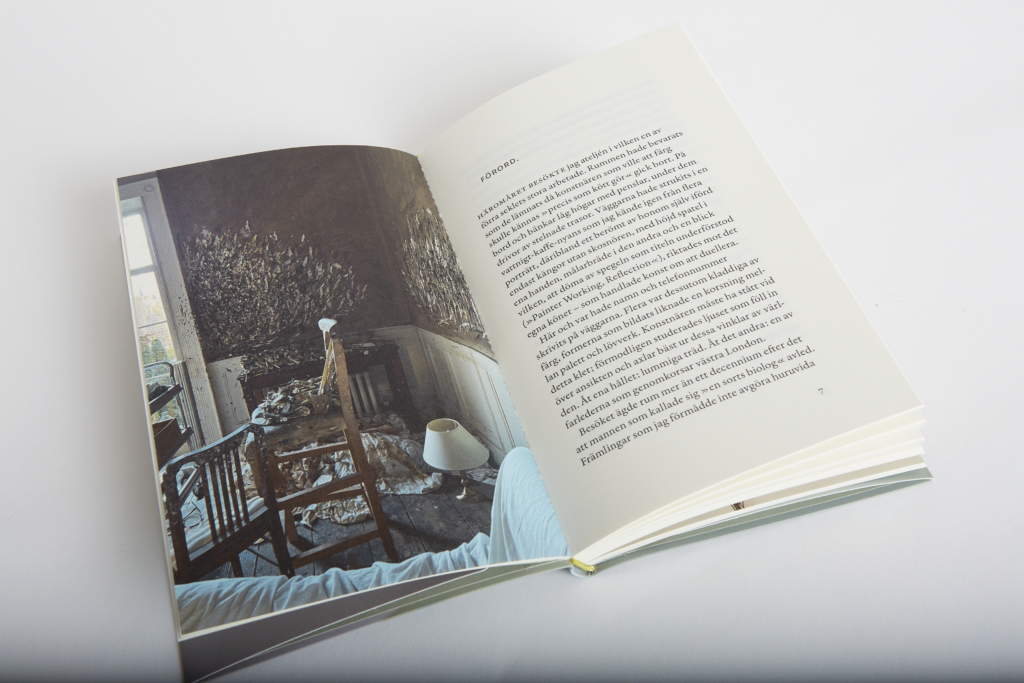

Foreword

A couple of years ago I visited the studio in which one of the last century’s greats worked. The rooms were preserved as they had been left when the artist, who wanted paint to feel »just like flesh does«, passed away. On tables and benches lay piles of brushes, under them drifts of stiff rags. The walls had been painted a watery-coffee shade that I recognized from several portraits, including a famous one of himself wearing only lace-less boots, wielding a spatula in one hand, a painting board in the other and a gaze (to judge from the mirror implied by the title, »Painter Working, Reflection«) directed at his own genitals – as if the act of art were a duel. Here and there names and telephone numbers had been written on the walls. Several were also tarnished with paint, the resulting shapes resembling a cross between palette and foliage. The artist must have stood next to this smear; the light falling on faces and shoulders was probably best studied from this corner of the world. On one side: lush trees. On the other: one of the throughfares that traverses west London.

The visit took place more than a decade after the man who considered himself »a kind of biologist« passed away. Strangers like me were unable to determine whether his spirit still haunted the studio. Yet everything in these forty or fifty square metres between traffic and garden breathed calm, clarity, concentration. In a word: presence of mind.

When I wondered about the bathtub in an adjacent storage room, the host, who had been a model for twenty years, told me that the artist had the habit of lying in it up to four times a day. He may have suffered from a washing compulsion – I don’t know and refrained from asking. But there are few situations in which a person is more aware of himself as a body. And in none so close to his original state. Were there better conditions for colours made flesh, over and over again, and always as if for the first time?

After the visit, the storage room did not leave my thoughts. For as long as I can remember, bathing in a tub has been the greatest of treats. Showers are for a quick wash and instant freshness; a person who lowers himself into the enamelled vessel, though, wants to protract time and rest idle in himself – at once weighted with life and a few kilos lighter than the scales would indicate. Personally, I prefer armpit-deep tubs with separate taps for hot and cold water. It is a delightful, somewhat ceremonial feeling to wait for the waters to mix and reach the right temperature. If you plunge your hand into the whorls, chill currents still dart through that winning warmth.

Soon.

Now.

In my youth, surrounded by bath foam, I could never leave alone the chain that gleamed intermittently at my feet, attached to a black rubber stopper. If I twisted the chain with my toes, I could pull it, carefully yet resolutely, until the tub suddenly let out a greedy gurgle – as if, curiously enough, it was about to drown. I can still indulge in the game today, but bathtubs with stoppers have become fewer. More often they have a pop-up stopper valve controlled by knob at the tap end of the tub. The tinny sounds a body makes when it moves are as amusing as ever, but one of the placid pleasures of bathing is in danger of being lost.

Is the chain not reminiscent of an umbilical cord? If so, the navel would be located directly below the taps. But I may be wrong. Similes may be striking, but they can also mislead. Perhaps the tub offers a more profane version of the baptismal font? When the bather emerges from it, he does so in some way as a new person. Regardless of whether the hole has been fitted with a valve or still has a stopper, and regardless of whether I amuse myself by unsettling a symbolic centre of existence or have installed myself in a worldly baptismal font, both I and time are diluted a little. In this enamelled piece of furniture, the body condenses into its essence while at the same time pleasantly dissolving. I wonder if it is not this experience of being at once more and less than oneself that makes bathing in a tub so . . . satisfying.

the following considerations seek to understand how the strong but paradoxical sensation of presence that a body immersed in water gives rise to is converted into literature. What is it Paul Valéry writes in one of his prose poems? »The living body is hardly different from the formless body which replaces it at every movement.« He could, I believe, just as well be speaking about how the anatomy appears when an author transitions from private to writing self. The transformation becomes particularly clear if the text does not speak in the first person singular but in the third, although even then there are of course ways of conveying presence that do not deny the person behind the work.

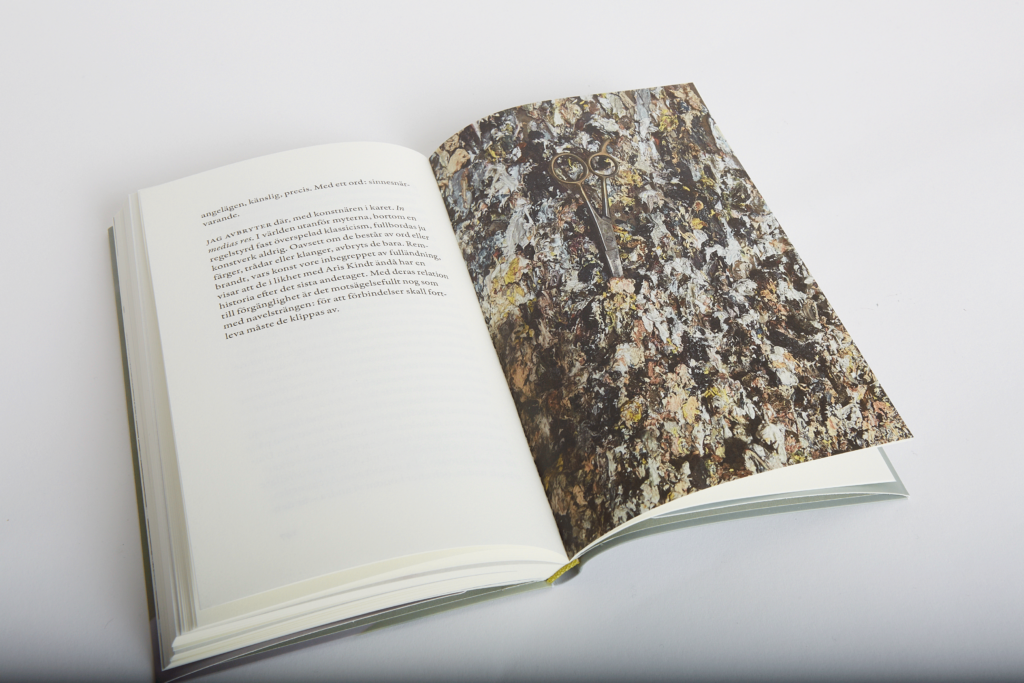

The self-portrait of the man whose bathtub made me pensive reflects the »artist at work«. I use neither a palette knife nor oil paint, so instead I will reflect on the body of a writer with the support of texts from ancient times through the present (as well as some works of my own and three works of art). The reflections concern urge as a condition for the coming into being of anything, hunger as a demanding experience and electricity as a way of being both in and outside of oneself.

In short: What makes literature »urgent«, »subtle« and »concise«, to use three adjectives that were also written on the coffee-brown walls in Kensington? Or, if one may be permitted to reformulate Lucian Freud’s wish, whose studio I visited that afternoon in April: How to make words feel like flesh?

Pages 9–11.

Reviews

»[Fioretos’s essays are] well-versed and civilized, yet lively and engaging. He manages to write about his own works without sounding self-absorbed, and he also makes a point of arguing for the privilege of being ›enraptured‹ as a reader – a rather important clarification in these times that suggest that the critic should be like a post-mortem pathologist who tugs and pulls at the (dead?) text. Rapture as an aesthetic criterion for professional reading – I can think of worse alternatives.« – Bernur, howsoftthisprisonis.blogspot.com

»Aris Fioretos likes to bathe in bathtubs. His new book of essays, Solar plexus, begins and ends with the pleasant feeling that arises when you immerse yourself in the warm water of a bathtub. It is a metaphor, of course. With his book, Fioretos wants to explore how the strong but paradoxical sensation of presence that a body immersed in water gives rise to may be translated into literature. An exploration of the secret power of literature, in other words. How might it affect us? How might it meld with the reader? . . . Solar plexus is a multidimensional book of essays with many openings, considerably more than those described here. [T]hey are rewarding reading, clear and almost educational.« – Stefan Eklund, Svenska Dagbladet

»Entertaining, edifying and very exciting about the power of literature.« – »Kritikerlistan« (The Critics’ List), Barometern and other papers

»Solar Plexus is a book that has challenged and enriched me. The language is easily accessible even though the images are profound and subtle. The word body is transformed into the different layers of an Arachne web, or a network of threads. Absent here is a hallmark of biography, the fixation on ›I‹ – instead the paths are more fictional, letting the reader catch glimpses of that ›I‹. That’s nice. And all the digressions that seek to strengthen the sense of immediacy are marked by an erudition in which the Greek heritage is clearly visible. It becomes like a chamber play where words have resonances, where literature with a capital L appears as a body in itself, tying together inner and outer worlds, ›you become what you eat‹ in the universe of words.« – Gunilla Lindblad, Dast Magazine

»[This is] a celebration of knowledge: a centrifuge in which analysis and recollections, impressions and fancies whirl around at great speed. . . . In Solar plexus, Aris Fioretos takes impressive risks and uses everything he’s got in a concerted attempt to reach the very core of his work. In essence, his book is about what art and literature are capable of.« – Karin Nykvist, Dagens Nyheter

»Aris Fioretos is subjective – the essayist must be. In his new book Solar plexus, he examines the body and literature. But what you remember after reading is spirit and text. Or perhaps the ability of reading to create a world that breaks the mold of the text and creates connections that you didn’t know existed. To put it more simply: Fioretos’s method is encyclopedic, but his order is a beautiful chaos. . . . For readers who allow themselves to give in and just go along, great pleasure awaits.« – Jan-Ove Nyström, Upsala Nya Tidning

»If it is still possible to write more masculine or more feminine essays, Aris Fioretos definitely belongs in the latter category. There is something about his attention to the body. At the same time so wild and so hypersensitive. . . . As always, Fioretos artfully balances whim and rigour. There is no serendipity here. Instead, he constructs his arguments methodically and lays bare the connecting elements. . . . Fioretos’s essays are full of erotic sensations. The parts of world literature closest to him, including the visual arts and not least music, seem to be fused with his body. It trembles, shakes, shudders, purrs. Stippled up in this, biographical details flare up like a line of cocaine. Thus world and self are electrified in this Elysian volume.« – Jesper Strömbäck Eklund, Expressen

»Raised in Lund with a father from Greece and a mother from Austria, Aris Fioretos is a polyglot and versatile poet and intellectual, equally at home among the gods of antiquity and on German literary arenas. . . . This summer he gave the prestigious annual ›poetics lectures‹ at the Goethe University in Frankfurt. These reflections on ›a writer and his body‹ form the basis for Solar plexus. The three essays are woven together into a skein, the symbol of which may be the very bundle of nerve cells located somewhere between navel and nipples that provides the book with its title. . . . In the middle essay, entitled ›Hunger‹, Fioretos unexpectedly recounts the story of how he battled with self-starvation as a young man. It fits into a few pages. But it is the productive pain point of these essays, and perhaps of his entire œuvre. Isn’t it contradictory that such a programmatically ego-shy author exposes his solar plexus in this manner? One might think so. But he does it in order to prime us for a decisive counterattack. Fioretos manages to land heavy blows for a literature in which the author makes himself known through the nerve fibres of his text, in the hurt and happiness it forces upon both creator and reader.« – Per Svensson, Sydsvenskan

»A battle cry for literature by a true intellectual who exposes his solar plexus.« – »Tio böcker att ha koll på« (Ten Books to Be Aware of), Sydsvenskan and other papers

Links

Talk with Jessika Gedin about »Solar plexus«, SVT Babel, February 3, 2025 (in Swedish)