Mary

(Mary)

Information · Cover · Extract · Reviews · Links

Information

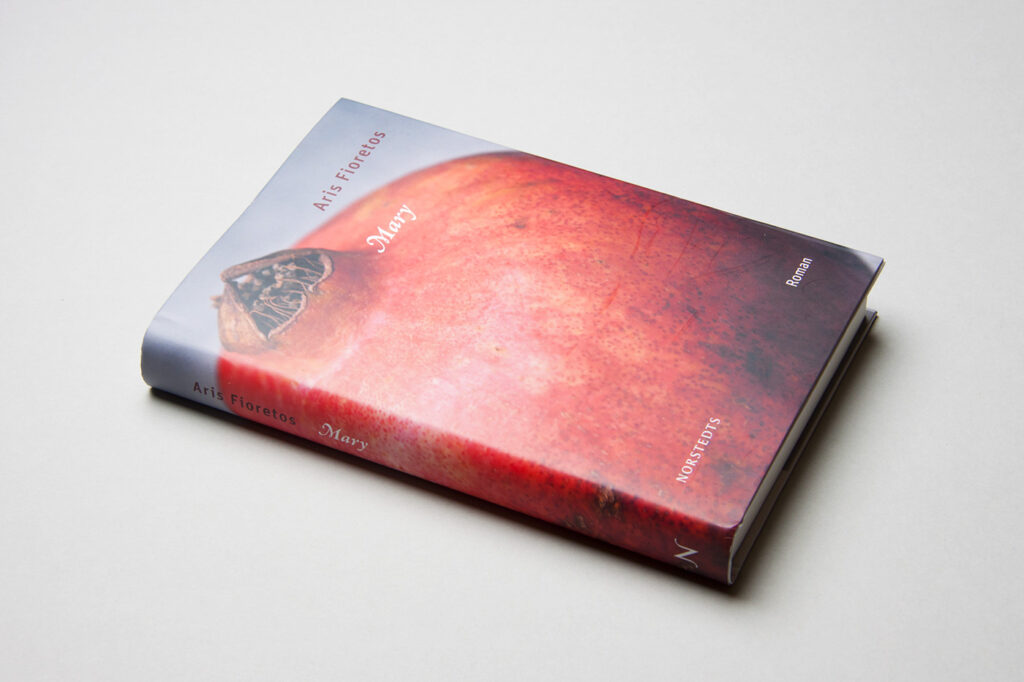

Novel · Stockholm: Norstedts, 2015, 320 pages · Cover: Birgit Schlegel, gewerkdesign Berlin · Cover photo: Thomas Florschuetz, Untitled, 2015 · ISBN 978-91-1-306482-6 · Complete translation and English language rights available

Cover

»I cover the scraps of paper in words as doggedly as the women mumble their sooty prayers in church. So long as one thing follows another I feel no fear, no regret. When no more words fit, each scrap goes with the others in the pewter box I was given at the funeral. There they lie tightly packed yet separate, as if they were pomegranate seeds, even though they look nothing like them.

Sometimes I wonder what I am doing, then I realise I have no choice. This is going to sound strange, but I am the only one who can recount how I ended.«

Mary P. is 23 years old and an architecture student in a country run by the military. Her boyfriend is a political activist and is planning a revolt. One November night in 1973 Mary is arrested for subversive activities. For thirteen days and nights she is held at the notorious headquarters of the security services, the place with Heaven and Minus Two. After that, only one question remains: who decides about a life?

Aris Fioretos’ new novel is a tale of passion about a young person’s yearning for freedom, a story of political violence and women’s solidarity. But above all it is about a body – its pain and desire, its yearning and its most secret transformations.

*

Aris Fioretos’ previous book was the widely acclaimed Halva Solen (»Half the Sun«, 2012), which has also drawn international praise. He has translated Friedrich Hölderlin and Vladimir Nabokov, among others, into Swedish; recent awards include the Grand Prize by Samfundet De nio, the Kellgren Prize by the Swedish Academy and Sveriges Radios’ Novel Prize.

»Halva solen is a beautiful book, funny and poignant. The seemingly objective narrative quivers with a deeply felt warmth and restrained sorrow.« – Dagens Nyheter

»Halva solen is a rich and abundantly generous book . . . [T]he love and light touch that define Aris Fioretos’ writing make it a true delight to read.« – Svenska Dagbladet

». . . a future classic.« – Upsala Nya Tidning

Extract

Chapter One

In the last photo from November I am wearing a denim jacket, a polo shirt, and the kind of pants that Stella calls “slacks.” Loafers, a felt bag over one shoulder. If my oldest friend were to see the photo she would assume that I’m my usual weight, a few kilos over fifty. Personally I feel bloated. My face is fuller than when I walked through the gates of the Polytechnic last fall. My neck seems plumper as well, though that could be because of the polo collar. My eyebrows are two broad pencil strokes; my lips are closed. My mouth makes me look guarded—or “reserved,” as Dimos likes to say. In the picture I am writing in a notebook pressed against my thigh. My body is twisted to the side; the shadows are plentiful and strange because the light is falling from various sources—streetlights and shop windows, maybe a floodlight. Under the photo, someone has jotted: Cripple.

I was christened Maria. That’s what it says on the ID card I tossed on the shelf in Dimos’s kitchen. The card says that I am twenty-three. A few years ago, I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to be so old; now I’m already in my last year of studying architecture. All I have left is to write my thesis. It will concern multi-family units in urban environments, but I haven’t made much progress yet. I don’t know if I’m going to be a structural engineer, a landscape architect, or a regular architect. I’m guessing regular architect; anyway, that’s what I would prefer. When I was little I was called Daughter or Ladybug, or on occasion Polio Girl—the illness explains my limp. I have also been called other names, but I don’t want to get into that. Dimos calls me Mary. From now on, that will be my name.

Mary. The Reserved.

The studs on the left breast pocket of my jacket aren’t visible in the picture. I stuck them there after the doctor’s visit—I can be superstitious sometimes. It’s strange, but even as I am filled with the mildest worry it’s like I carry a sun in my belly, trembling like a clenched fist of joy.

It’s seven in the evening when I wake up. I hadn’t meant to fall asleep. But when I returned from the doctor, my body was heavy as damp earth, my head light as ether. It was enough to lie down on the bed.

Now I realize that I slept without dreams, without memories, as if my body needed a rest from the labor of being human. Dimos’s side is empty. My boyfriend has been at the Polytechnic since Wednesday. This morning he came home to shower and pick up a few things. He knew I was going to the doctor after lunch, but he still thinks the visit had to do with my joint pain. I’ll tell him in a little while, when I see him. The fan turns lazily but methodically on the ceiling. Even though it’s autumn, the days are warm, especially in this oven of an apartment. If I hold my breath long enough, sweat trickles out at my hairline. After a while, it forms a drop big enough to run down my temple. It slides alongside my ear, tickles a bit, and disappears into the hair at my nape.

The runnel reminds me of the picture I saw in the paper a few days ago, after my first visit to the doctor, when I only had a lab test. A boy was sitting with a blanket over his shoulders, his eyes wide open; the tears had left furrows in his inexplicably dirty face. His cheeks looked like a ravaged floodplain. He was holding a sooty clump in his arms. Only when I read the caption did I understand. The six-year-old with his teddy bear. Survived the fire that claimed his whole family.

I cried like a baby.

If Olympia Street were engulfed, I would not hesitate to run into the sea of flames to save the inhabitants—even though no one would thank me, least of all Mother, and even though Theo left the country a long time ago. Yet as recently as a few years ago I wanted nothing more than to be an orphan. Anything to avoid suffocating in this private version of what the military calls the Church, the Family, and our Holy Nation.

This feeling didn’t leave me until I moved in with Stella. No, that’s not true. It actually lingered until the boy with the ponytail. I had seen him in the hallways with friends, or near the main entrance where people sell used textbooks. And I had noticed him sneaking looks. But the truth is, I didn’t think about it much more, so when he crossed the boulevard early last school year and headed straight for me, I was so surprised that I didn’t hear what he said. I had just said goodbye to Stella and was on my way in through the gates when the boy spoke to me. He seemed twice as large as a regular person, which didn’t exactly help. I excused myself without listening. The lecture had started, I was in a hurry, another time—words of that nature.

Perhaps my guilty conscience made the difference. In any case, before I walked into the main building I turned around and saw the guy standing where I’d left him. As if he had taken root. This would become my first image of Dimos, and it made my memory more vivid than it would have been otherwise. The surroundings paled with time—the shabby palm trees, the trash cans, the bustle at the gates. All that was left was the clipped silhouette of a figure. Planted, steadfast, a tree of a person.

Someone told me that he was active in the student organizations, and occasionally I was overcome with a persistent warmth when I thought of how he had stood so obliviously at the gate. Yet the image crumbled away. Besides, I was going out with one of Stella’s classmates from the English department, and for a while that brought disorder to my life. His name is Antonis, but he has almost nothing to do with this story.

Last spring, I discovered The Tree again. This was at an Automat restaurant across from the National Museum where I sometimes eat lunch when I don’t feel up to going home. And suddenly that muscle in my chest started acting like a sparrow. The Tree was sitting in the only booth with a free seat, absorbed in a blueprint. He was eating without thinking about the food; I doubt he’d had a haircut since the last time we’d spoken. Now he also had a straggly beard, which made him look like a cross between a novice monk and a rock star. When I asked if he minded if I took a seat, I received only a grunt in return. Ten minutes passed. The jukebox in the next booth was playing a hit from an American TV show about a boy band:

This one thing I will vow ya

I’d rather die than to live without ya

I ate as The Tree, busy with his blueprint, continued to bring his spoon to his mouth even when there was nothing left on his plate. It was amusing to watch, but instead of laughing I studied, for the first time, a stranger’s hands. The long, sinewy fingers, the surprisingly well-manicured nails, the veins that wound between the knuckles like worms. And those freckles, dusted across his skin like the finest powder. To my astonishment, I found that he seemed much more interesting than I had first thought. When fifteen minutes passed and he still hadn’t raised his eyes, however, I decided I’d had enough. It was one thing to be oblivious, but politeness is another matter. I pushed my chair back in. Yet instead of leaving, I leaned over with my tray in hand.

“You’re eating air, do you know that?” My voice sounded harsher than I meant it to. He looked at the spoon, and then at me. For a moment so drawn out that I would later examine each part of the memory as if through a magnifying glass, I witnessed his transformation from bewilderment to surprise. When he realized who I was, he caught his breath. His inhalation was so earnest, and so open, that it gave me a shock of affinity. Smiling but nervous, he pretended to swallow, and I understood it was probably best to sit down again. “I’m sorry.” My tray clattered. “I think I was a little bit rude last time.”

That’s all. That’s how we became a couple. As The Tree rolled up his blueprint, he told me his name. I had heard it before, who hasn’t, but I didn’t know it was the guy who had been eyeing me in the hallways. Maybe he wanted me to admire him. Maybe he thought I would be impressed because he was one of the Free Students. But when I introduced myself, he only asked: “Daughter of the Captain?” I had been expecting many things, but not that. The sparrow stopped its fluttering; I tried to get up. No matter what I replied, it would be wrong. “You can start or stop.” He saw my confusion. “That is, I mean, can’t we be people who start—I mean, get to know each other?” I wasn’t sure that the grammar was quite right, but I put down my tray. He popped a coin into the jukebox and selected the song that had just been playing. “May I call you Mary?”

The apartment, before I lock it without knowing it will be for the last time.

The walls are the pale green of an unripe melon; the floor is marble. A pair of sawhorses with a board on top stands in one corner; the chair is hidden under clothes. The vase by the door was left behind by the last tenant. It is large and round and dusty, and the cattails in it shed each time the door opens or closes. Dimos claims that he likes to watch the fluff swirl through the air like dry snowflakes, but I suspect he’s just too lazy to throw out the reeds. My felt bag hangs from the bathroom door; next to the alarm clock are The Prison Notebooks and a book on material mechanics. A torn bit of postcard is sticking out like a bookmark; it’s possible to make out part of a hand and a piece of fruit. Aside from the textbook and the clothes, all that belongs to me is one of the cassette tapes. I spend several nights a week with Dimos, but it’s so messy that you might never find your things again if you leave them here. Above the desk, the newspaper-clipping picture of a laughing boxer has new company—the boy with the sooty stuffed animal.

Down on the street, a motorcycle revs, and cars honk and brake. The neighborhood lotto-seller calls out the winnings for tomorrow’s drawing; I can hear women gathering the washing in the building next door. Someone flushes a toilet somewhere deeper within the building, now and then the elevator starts up. Even though the bathroom is closed, I can hear the faucet dripping with tiny, precise chisel taps. When I visited the apartment for the first time, I mentioned that it would be simple to replace the gasket. But Dimos just laughed his bright laughter. The pressure in the pipes was so weak that a person ought to be thankful for each drop. His apartment is on the top floor. When you exit the elevator on the fifth floor, you have to walk up one more flight of stairs. There are two doors. One leads out to the roof; the other is to his one-bedroom apartment with a shower and kitchenette. A cistern takes up half the space, and the rest is the elevator shaft and the terrace that belongs to the building. He tidied up his clothes and some dirty dishes, raised the blinds with a few hefty tugs, then explained that the terrace was what made him move in. Fifty square meters under the sky, surrounded by clotheslines and TV antennas. There was no greater freedom to be had in this country.

As soon as I get to my feet, I bend over. The blood rushes to my head like water soaking a sponge. Dr. Kolver says that dizziness is common early on, and nausea as well. The next few weeks might be rough, she explained, but then it will get better. When the attack is over I put away my ID card. By law, all citizens must carry their documents on them, but according to Dimos it’s better to pay the fine. “A person has the right to remain anonymous.” I think this is something he read in Gramsci. Anyway, for the most part, the police will let you go.

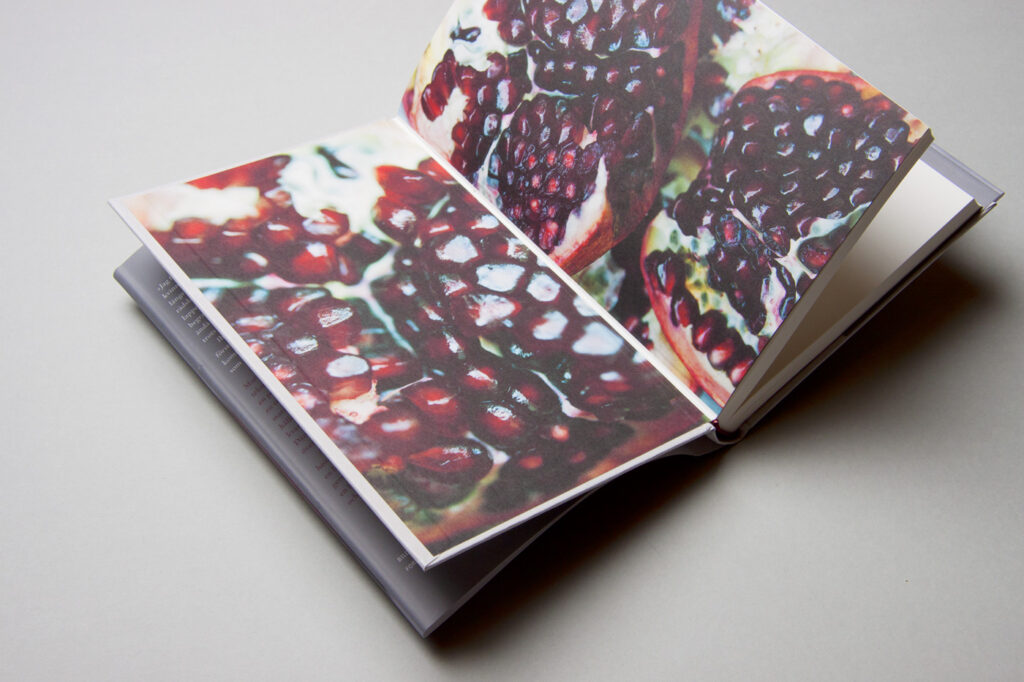

I rewind the cassette. As the tape flutters and chafes I light the stove. The flame flashes to life, blue as ice. One of last autumn’s pomegranates is on the table, next to the Turkish coffee mill, which was also something my boyfriend bought. Its crank looked so elegantly Oriental that he didn’t bother to haggle. He claims that you only need to look at the mill to smell the scent of coffee. Now I wonder how much time will pass before we use it. The pomegranate is already so dried out the seeds rattle if you shake it.

On the shelf is a pack of red Santés that Dimos must have forgotten. Seven left. I have decided to quit, but so far I’ve only banned myself from buying my own cigarettes. Once I’ve lit one by the gas flame I stir sugar into the coffee. The grounds swirl up and settle. When I think of how Dimos will react, I become both eager and nervous. My belly feels more and more like a tingling web of sunlight. On my way out to the terrace I press PLAY.

Exhaust fumes have eaten their way into the marble since the building was erected ten years ago. It doesn’t matter how often we mop, it’s still like walking on a thin layer of ash. Dimos doesn’t want to hear about it—he claps his hands over his ears and starts singing that Monkees song—but I’m convinced that the marble wasn’t properly treated. It has to be polished and waxed for its porous surface to be correctly sealed. Really, any workman ought to know that. I sit with my back against the cistern. The water laps inside it, enormous and yet light as a feather. The coffee burns me; the women on the roof across the way are almost finished. Both of them press their chins against the laundry as they walk to the stairs with their brimming baskets. They say hello; I wave back. I think I’ll propose that the terrace be repaired. The marble can be polished again, and if the railing were covered with bast we would avoid any accidents. After our siesta we would see the laundry drying; in the evening we would see the darkness falling, and at night we could study the constellations, chilly as diamonds and inconceivably distant.

So make a stand for your man, honey

Try to can the can

Nothing against boy bands, but I prefer women in denim jackets. The bassline pounds, rumbling through my veins, the tar burns black and harsh in my lungs. The cigarette bobs at the corner of my mouth as I sing along with Suzi Quatro. For the first time I exist in the world that exists inside me, built around a sun no larger than a single grain. To think that life can feel so light.

I’m still singing when I come out onto the street. Now I’m dressed like in the last photo—all in black, save for my jacket. My feet carry me down the hill as if they have a life of their own. Trash is piled outside the stores. It must be pick-up night tonight. One shop owner is talking to a customer as he knocks the bottoms out of a few boxes and folds the stiff cardboard. I walk onto the street and alongside the parked cars. Ahead of me, a man in a tunic shirt is out for a walk. Hands behind his back; the prayer beads slide between his fingers according to some secret ritual. He, too, is moving more quickly than usual, although he turns before I catch up to him. Instead a yellow trolley bus comes swaying up the hill. The two cables that link it to the wires make it look like a giant grasshopper. A passenger is just pulling the cord, then she stands up to get off.

I have promised to give Stella a call, but first I go to the pharmacy to pick up new pills for my aching joints. I also buy the items Dimos asked for. As soon as I come back out I scrape the prescription label off the tube of pills, and then I cross the avenue and walk into the park. The cypresses look like rockets ready to fire; the whitewashed gutters are reminiscent of runways. A couple of older men are sitting on a bench with sunflower seeds around their feet. The shells gape like fish mouths. A mother is pushing a baby carriage as she leans over to talk to her little Buddha, sitting grave and upright with hands resting on either side of the carriage. Two schoolgirls are hurrying home from evening lessons—cardigans over their uniforms, books and folders pressed to their chests.

Mosquitoes whirl about the newspapers at the kiosk in the middle of the park. A woman counts coins behind the piles of cigarette packs and the colossal telephone. I buy a double spearmint, and read the headlines as I put away my change. The October earthquake has claimed another victim. This time it’s an old woman who never regained consciousness after being rescued from the ruins. The government announces that the Sixth Fleet will remain in the bay. A relationship has been established with the new leadership in Chile. The country’s students are encouraged to be industrious and disciplined. Following his victory against Norton in September, Ali wants to fight Frazier for a new title.

In the distance I hear the shouts ring out, wound in cotton.

The closer I get to the Polytechnic, the more clearly I can make out the exclamation marks:

“And one, and one—and four! And one, and one—and four!”

“Down with the junta! Down with the junta! Down with the junta!”

“Do something, good people! They’re taking our bread!”

The protests are in their third day. People hurry along the streets. Many are carrying planks and bricks; others, necessities. The future of the country is being determined here and now. It started with the economists last winter and was picked up by the law students during the spring; the first unrest after years of stagnation. During the summer the protests gathered strength, even out in the country, and now they have swollen into a wave of discontent.

I turn down onto the broad boulevard that leads past the National Archaeological Museum and the Polytechnic—and all at once I see the sea of people. There must be thousands of them crowding in front of the main gate. Banners wave, slogans are chanted, megaphones crackle and whine. The shop owners have pulled down their roller fronts; the kiosks are still open. A few meters ahead of me, a bus gives up. Its hydraulic pumps give a sluggish hiss. Those who wish to can get off before the driver takes a detour around the area. Two or three cars attempt to crowd their way through, but they are redirected by students with leaflets in hand. The proclamations are shoved under windshield wipers or stuck through windows. The police are still watching without intervening. The plainclothes men with sunglasses are standing in front of the hotel across the boulevard. They, too, watch without doing anything. It seems this evening will be like yesterday.

People are climbing the bars along the boulevard. Occasionally there is a flash from the metal sheeting that was hung up on the first day to blind the Intelligence Service’s cameras in the building across the way. Now there are other chants:

“We are the Free Besieged!”

“We are made of wood! The night is made of wood! Why do you bring fire?”

And meanwhile there is the sound of a great, dull swell under the shouts, the one that carries all the other slogans: “Bread—education—freedom! Bread—education—freedom! Bread—education—freedom!”

Two third-year guys are standing outside the Automat restaurant. A week ago, one of them asked me about my thesis; now he’s writing in a notebook. Each time he fills a page he gives it to his friend, who immediately hands it on to a passerby. Before the bus turns down toward the fabric district, the driver leans out the window. “What is your message, boys?” Laughing, they reply: “114!” That’s the last paragraph in our abolished constitution, in which patriots are entrusted with the task of upholding the constitution of the state. As the bus stands still, other students write on its metal sides with markers. One guy paints a giant white peace sign on the radiator. When he asks if he can replace the destination above the windshield with DEMOCRACY, the driver jerks his hand sideways in the air, as if he’s chopping vegetables: don’t you dare. A pair of girls runs past, one brandishing a broom, the other with a flag draped over her shoulders. “It’s happening, it’s happening!” They might be right. It doesn’t seem as if the military is planning to intervene.

I see two men with leather jackets and sunglasses over by the kiosk; one of them with a camera around his neck. I wait until they have disappeared into the crowd, then I buy notebooks. They are the same ones I usually use for sketching: dark blue cover, sixty-four unlined pages. When I ask what I should write, the guys suggest slogans in French or English, but I stick to 114. Without an exclamation mark. It may sound strange, but I don’t like that mark. As soon as I’ve torn out a page, it is taken from me. Others are handing out leaflets beside us. Or else someone calls: “Sit, sit!” And right away, twenty people sit down and start singing. A man who can’t get anywhere in his car rolls down his window and asks my name. I shake my head. Then he wants to give me a coin to buy another notebook. I shake my head again. Not with other people’s money.

And so it continues. For a long time, the sky is pink as scratched skin. Then darkness falls.

Sometimes I, too, sit on the street with my arms around strange shoulders, singing at the top of my lungs. It’s as if a storm of flowers were pounding in my blood. Or else I talk to friends and learn what happened while I was sleeping in at Dimos’s. But for the most part I write, seized by defiance and joy. After nearly seven years, it’s happening. Everything people have been dreaming of, it’s really happening. When the notebooks are used up, I buy new ones. In the end I can barely see what my hand is writing.

As soon as the streetlights come on, the speakers start to crackle, then there’s a voice that I recognize. “Here is the Polytechnic, here is the Polytechnic! This is the radio station of the Free Students.” Calmly it lists the items needed inside the area: bread, water, Vaseline, compresses, rubbing alcohol … After that come the demands for freedom of assembly, freedom of the press, free speech, academic freedom. Following this the voice recites names. It has done so since the occupation began on Wednesday, always after the lights have been turned on but before night has fallen. The names belong to people who are presumed to be moving in the shadows. How the Free Students got hold of them is a secret. “Greetings, Deputy Aide Samaritis, thirty-six, father of two. Do not use violence against your brothers and sisters. Greetings, Inspector Lamas, age unknown but our brother. Do not use violence. Greetings, Lieutenant Klendros, twenty-nine and father of one boy. You must also refrain from using violence against your brothers and sisters. Greetings, Captain Petr…”

Dimos will continue to recite names for another hour. I promised to come before he started, but now I’m in no rush. As long as he’s at the microphone, he doesn’t have time anyway.

The evening grows denser, like smoke. After a while, people start lighting fires on the sidewalks. They wander and flicker, yet it’s hard to see who is moving around in the dark. Only now do I sense the unrest in the air. Presumably it’s because this is the third night and exhaustion is taking a toll, but the atmosphere seems more feverish—as if the darkness were just being rubbed with a cat’s fur. Suddenly someone shoves me in the side. “Look out, they’ve seen you!” I notice one of the leather jackets by the kiosk, lowering his camera. The third-years guys have vanished; people jostle and shout. Most of them are pushing toward the gates, but more and more are moving in the opposite direction. I shove my notebook into my bag. Time to get in to see Dimos.

The closer I get to the main gate, the more crowded it becomes. People aren’t just hanging from the bars along the boulevard, they’re also sitting in the palm trees and the lampposts inside. Several of them wonder if I’ve seen anything. When I ask what they mean, they cry: “The military! Are they coming? The military!” Until now, the Polytechnic has been under guard by police and the men from the Intelligence Service, but everyone fears that soldiers will be called in from the camps outside the city. That would mean that the government does not intend to allow the protests to continue. No one knows what would happen if this were the case. From within the gates, people chant that the school is a free zone, and yet I can see that several people are holding chair legs in their hands, some even carry stockings filled with sand. Others shout with raised fists.

“Yuppi ya ya, yuppi yuppi ya, yuppi ya ya, yuppi yuppi ya…”

“We are the Free Students!”

Over the loudspeaker, Dimos exhorts the police not to use violence, then continues to recite names. The metal sheeting flashes in the electric light. The sound is deafening.

I know I have to get in before midnight; after that they won’t even let nurses in. On the first night, the occupiers were surprised by the Intelligence Service. The men had dressed in white coats, a few were even wearing stethoscopes around their necks. They’d hardly made it in before they let loose with batons and blackjacks. Dozens of people were injured; some with life-threatening wounds. The ambulances couldn’t reach them until the next morning. After protests from the Red Cross the police have remained outside, but no one knows how much longer that will last.

The electricity is cut off just before midnight. From one moment to the next, the area is plunged into darkness. Only the police floodlights at the main entrance are still functional—as well as the Polytechnic’s generator, which makes the main building glow like a pale jewel in the night.

Strangely enough, I feel safe. Cigarettes glimmer in the darkness, people sing and shout. Even though it’s nighttime, no one seems to seriously think that something will happen, not in this sea of hope and people. The warmth, the sweat, the proximity of whistling and shouting bodies—everything lends protection. Yet reluctantly I notice that I am no longer taking for granted that the shoves mean well. I find myself instinctively clutching my stomach several times. Sirens wail in the distance; it seems that ambulances are on the way. Then I hear a megaphone, and a voice as thin as aluminum foil declares that the authorities will not tolerate more vandalism. The law must be respected; they will do whatever is necessary to restore order. People at the Polytechnic or on the surrounding streets have thirty minutes to disperse before the authorities step in. This warning is to be taken seriously.

Protests come from the darkness:

“If you stay, we stay!”

“The streets belong to everyone!”

“You can take our lives, but not the night!”

It is too late to turn back, and what would be the point? The city belongs to those demonstrating as much as it does the authorities. The police can force people to go home, or arrest those who stay. But tomorrow the protests will continue.

More and more people begin to chant: “Sit, sit, sit!” And one by one, we sit down. People hold up lighters, glasses gleam in the dim light, defiance will win out. When I see the shapes, it feels as if the night has grown contours. On the streets and sidewalks, on the benches, in the flowerbeds, and under the dark lampposts—everywhere there are shapes of darkness and resistance that refuse to be frightened, refuse to be silenced, refuse to give up. The police cannot arrest or chase away all of them. Even if there aren’t as many protestors as there were yesterday, there are too many of them, and what’s more, they are part of the night. Someone starts to sing; others chime in. In the end, the night quivers like leaves.

I can’t say how much time passes before shrill cries are heard near the main gate. Shortly thereafter, tumult breaks out. Someone shouts that there are snipers on the rooftops, everyone has to take cover. People stand up and start to run—no one knows where to, the important thing is away. I only have time to think: Now it begins.

With my bag clamped under my arm, I move toward the cross streets. The people coming from the main gate are holding their stomachs or heads. A girl vomits by a wall as her boyfriend tugs at her. The students’ loudspeaker can still be heard, but the voice no longer belongs to Dimos. Instead, a woman urges: “Comrades, do not leave the streets! Do not leave the streets!” It sounds like Red Flora.

Bangs echo between the buildings; fear spreads the way a sheet of ice cracks according to my brother. I can see soldiers approaching in the darkness. So the military has been called in. The men walk with backs to one another and rifles lifted to their shoulders. People make way, pressing close to walls or crowding into doorways. Then there is a harmless “pop.” Right away, several more. “Pop,” “pop,” “pop” … It takes a few seconds to realize what it is. Metal casings clatter across the street; the air fills with pungent smoke. And I panic.

Dimos says that it gets your eyes first. They start to sting and hurt, then your chest is compressed, and then comes the nausea. I know I mustn’t rub my eyes, but I can’t help it. I need my eyes, I need my eyes. People strike at the air around them, coughing and screaming. There is no avoiding the tear gas, breathing becomes more and more painful. Somehow I manage to make my way to a coffeehouse a few streets away. Maybe the man who warned me dragged me along. “Here, take this,” he says inside the building, and gives me his handkerchief. But first I look through my bag. Once I’ve smeared on the Vaseline, the handkerchief turns into a gooey paradise.

The pain slowly disappears, and yet it feels like a cat has dug its claws into my eyes. Bewildered I realize that the lights are working here. Through my tears I can see the chilled display case, piles of ashtrays in a corner, the clump in my hand. I promise myself to remember each object. Even the clock on the wall—it’s almost one in the morning—and the toothpicks gleaming on a plate, among cucumber slices and oil. But above all, the handkerchief. It is red with big black dots, like the dress I received when I was fourteen for bringing home good grades in everything but gym class.

I know I can’t stay. By now, the stranger has taken off. The men in the café are staring. Some of them are holding playing cards in their hands, others are smoking. No one says anything. Shouts and sirens can be heard from outside, and then the loudspeaker again—surprisingly clear even though the Polytechnic is several blocks away. “Do not shoot at your brothers, soldiers! Do not shoot!” Red Flora’s voice resounds through the night and the confusion. “Soldiers, we are brothers and sisters! We need doctors! Why are you shooting? Don’t shoot!”

Afterwards, I am ashamed that I give a curtsy before I go.

On the street there’s a dull clatter, the ground is trembling like pent-up thunder. It is difficult to say what is happening, but the shooting has ended and the air is thick with smoke. All over, people are coughing. Some of them are carrying supplies or tools; most of them are moving away from the Polytechnic. When I ask, they all shake their heads. No one knows what’s going on. I hurry along the facades with the handkerchief to my face, making an arc around the area. The side entrance is blockaded too, but if I can only make it there I expect I will be let in. There’s always someone who recognizes me. And if that isn’t enough, they can fetch Dimos. The guy with the freckles. Who built the radio transmitter. That tree of a man.

In the next block, a middle-aged couple is just unlocking a front door. I realize that I forgot to call Stella. Oh, hen shit. I wanted to talk to her after my siesta, but it didn’t even cross my mind as I was buying gum in the park. As I reach the door, the couple lets me in, but they don’t make any room in the elevator. I end up standing in front of the door, watching the numbers on the panel light up and be swallowed again. I decide to take the stairs. When I get to the top floor, I hear a key turning. I knock and ask if I can borrow their phone. No one opens; no one even responds.

The nausea intensifies. I managed to get it under control at the café, but now I’m starting to gag. As I wait for it to subside, I rub Vaseline around my eyes and nostrils. I count my breaths. I count them once more. After a while I get tired and I begin to count the ticks before the light goes out and the button must be pressed again. Thus the minutes pass. The doctor asked me to be careful, and the first thing I do is inhale tear gas. Stella would crucify me. I make double knots in my shoelaces; I blow my nose. Perhaps I can handle this after all.

I hardly make it back onto the street before I vomit. Almost nothing comes up, just coffee and what might have been a pie or pierogi—I no longer remember what I ate when I bought the studs at the hardware store after my doctor’s visit. At least I feel relief. There I stand, with my palms against my knees and snot running, waiting to be emptied. My legs quake, my stomach cramps, I wonder if parts of me might be damaged. When the convulsions stop, I realize I am at the dividing line. The houses behind me have power; the buildings in front of me are dark. A few more steps, and I would be standing with one foot on either side. Tea lights flicker in a few windows. People are likely hiding behind the curtains, silent witnesses to what is happening. Aren’t they going to do something?

I decide to continue along the dark side of the street. At the next intersection I make out diffuse shapes. They’re moving calmly and methodically, but it’s difficult to say what they’re up to. The longer I watch the shapes, the more convinced I become that they are soldiers. Probably they are blocking off the area. That would mean the Polytechnic is going to be stormed. During the planning of the occupation, everyone agreed that weapons should not be used. Dimos told me members of forbidden organizations still wanted to vote on the issue. Red Flora claimed that the military wouldn’t spare us just because we desired a peaceful solution to the education issue. In the end Dimos got up. The real question was whether it would be to the students’ advantage or disadvantage; violence breeds violence. Instead they could announce the names of men from the Intelligence Service. For example. Why should they remain anonymous when no one else was allowed to? That settled it.

As I consider how to get past the soldiers, a taxi crawls forward. No headlights, faint squeaking from the chassis. Later I realize that it must have followed me. The driver rolls down the window. Two people are sitting in the back seat; they must be students. One, a pimply girl, looks at me with an inscrutable gaze.

“Hurry. They’ll notice us soon.”

Once I’m seated in the car, it backs up and heads down toward the fabric district. After a while, the driver turns on the headlights. We trundle through deserted streets. He asks my name. Am I a student at the Polytechnic? Do I have friends inside? Feeling sick, all I manage to say is that it would be nice if he could drop me off at the square a few blocks away; I can walk from there. But as we approach, we see military police. Trucks have been driven up onto the sidewalk; motorcycles are parked next to a roadblock. It seems the square is being used as a base. There’s even a tank. A soldier waves. He’s wearing a white helmet and white gloves. The driver swerves onto a side street, swearing. Impossible to stop, might as well drive me home. Where did I say I lived, again?

On this side of the boulevard, the city seems evacuated. Empty streets, sacks of fabric remnants on poorly-lit sidewalks, chintzy tailor shops and warehouses. The car sways each time we drive over a hole in the asphalt. Then it feels like we are a team, the driver, the two in the back seat, and me—a sworn group, an endless night. No one says anything, but the man in the back seat smokes. This, too, strengthens the sense of togetherness, even though it makes me feel sick again. When we stop at an intersection, I see a matted dog digging through the garbage. It barks with its tail up and ears perked forward. This must have been what the city looked like nearly seven years ago, during the state of emergency that came along with what the school books call “the national revolution.” Empty, yet full of trash.

I decide to return as soon as the taxi has dropped me off. I don’t know how I’ll get in, but I don’t want another hour to pass without Dimos. Ten minutes later, the taxi passes the dog again. At first I don’t understand, but then I realize that those aren’t student sympathizers in the back seat. At that moment, the man in the back seat places his hand on my shoulder and asks for my felt bag. We immediately turn back toward the square. This time, the driver isn’t afraid to drive right up to the soldier. He rolls down the window and says, almost cheerfully, turning toward the girl in the back and then to me: “Two more.”

I can’t manage to form a single worthy thought.

Pages 13–32.

Reviews

»It is impossible not to be deeply touched by the detailed yet vivid descriptions of what life could be like for someone who became a prisoner of the Greek military dictatorship during the 1970s. Still, the narrative manages to be toned down without being overly detached. Everything is depicted in a way that makes it well-nigh impossible to stop reading . . . Mary is one of the most powerful Swedish novels I have read in a very long time.« – Clemens Altgård, Norra Skånes Tidningar

»Fioretos’s writing has probably never been tauter than this – each word points ahead and is followed up . . . And perhaps his writing has never been more beautiful either: the prose is of a kind that only a Swedish writer with Continental self-assurance can produce . . . – yes, he is quite excruciatingly sensuous.« – Tim Andersson, Arbetarebladet

»Aris Fioretos has pulled off an impressive literary feat. With Mary he reinforces his position as an important and singular voice in the world of Swedish letters. Setting out from an apparently simple story, albeit elegantly framed by the brief sections that open and close the novel, he has created a text that is like a whole life. And that is ultimately what this novel is about, I think. It wants to defend life. Mary carries a life, she carries memories of closeness, but also of grief, anger and disappointments. She has had an early insight into the transience of life. Fioretos lets Mary remember a dispute with her mother – and how it filled her with ›a certainty that everything, really everything in life disappears‹. Can I end that way? Cherish life, because it will disappear. Only great novelistic art can say that while remaining serious. Mary is great novelistic art. It is so because it unites thought and feeling, or as Mary says, weighing a pomegranate in the palm of her hand: ›… it looked like a cross between a heart and a skull‹.« – Stefan Eklund, Dagens Nyheter

»[Fioretos] has written a historical novel that strikes our time right in the pit of the stomach. It’s impossible not to read it against the backdrop of TV footage from today’s Greece. History doesn’t repeat itself, but read it right and it can teach us to see our own times more clearly.« – Torbjörn Elensky, Vi

»With his overwhelming and masterful novel, Mary, Fioretos [offers] . . . an initiated account of a period and its people so profoundly gripping that it really is hard to put the book down . . . (He) has written a brilliant and deeply moving novel – in fact, one of the best Swedish novels I have read in many years. Everyone should read it in order to gain a more profound perspective on what is happening in the world today.« – Mats Gellerfelt, Böckernas klubb

»Aris Fioretos’ Mary is an unpleasant book. A frightening reminder of something that happened not so long ago. It is also a very powerful book.« – Lennart Götesson, Dala-Demokraten

»Aris Fioretos’ characterisation from within a woman, his ability to step into a female first person who is carnally and psychologically utterly credible [is impressive]. Mary is a book we need!« – Anders Hjertén, Värmlands Folkblad

»Fioretos writes things into existence and gives them a rare lustre. This applies to details such as playing cards, cigarette packs, bits of soap, but above all to pomegranates. On an outing with Mary, her fiancé squeezes a pomegranate so hard that it bursts, with predictable results: ›His hand was a fountain of desire.‹ Later, Mary likens the mosquito bites they get when they sleep naked on the terrace, and when the ›indiscretion‹ occurs, to pomegranate seeds. This is a novel nourished by its low-intensity suspense. In that way it is not unlike a pregnancy, really – and remarkable as it may seem, it is indubitable this time that a male author has written insightfully about the female experience. Literature really is where life’s great paradoxes meet, and Aris Fioretos is good at making his way to them. There are plenty of moments here to fascinate and captivate the reader, and to allow us to get to know the memorable Mary.« – Björn Kohlström, Jönköpings-Posten

»There are authors, commentators and writers. And then there are poets. With his two latest books, The Last Greek and Half the Sun, Fioretos joined the prose artists at the very forefront of Swedish literature. This position he consolidates in the new novel, Mary … It is a book of life wisdom Aris Fioretos has written, shorn of all the pseudo-issues of our time and focused on life’s essential affirmation. I wonder if anything more beautifully sad, and yet more consoling, has been written in Swedish in recent years and this side of the millennium.« – Bo-Ingvar Kollberg, Upsala Nya Tidning

»Fioretos’ book is a reminder. He portrays the underworld of reality with an acuity, intensity and brilliance that make it difficult to put his book down even for a moment. It is a clamour that continues: the undying cries of the abducted Persephone. I think about IS, about trafficking, about violence in intimate relationships. Mary forces me not to stop thinking.« – Maria Küchen, Sydsvenskan

»Despite its sombre and cruel content, Mary is remarkably easy to read. It is not so much the stylistic elegance that impresses me as what Fioretos manages to achieve with simple means and such a limited setting. How vividly and truly thrillingly he succeeds in depicting the prisoners’ confined existence, the relationships between the stranded women, the fantasising about food, the lovely smell of soap. This is not just a brilliant novel, it is a deeply moving novel.« – Ann Lingebrandt, Norrköpings Tidningar

»The pull is immediate. Fioretos writes such dexterously lucid prose that each gust of wind, each flap of pigeons’ wings, each air conditioning unit and cigarette is delineated with a throbbing of life . . . In one sense, the story is completely conventional. Mary is one of many novels that traces the architecture of oppression, that portrays torture, rape and the soul-splintering violence of claustrophobia. And one of very many novels that takes a historic event and excavates from it a situation that serves as a mirror for our time … There is nothing wrong with either the former or the latter – and Fioretos does both very well –, but the reason Mary must be regarded as one of the best novels in recent years lies somewhere else altogether. For it is in the exceptional, tenderly lyrical concretion of Mary’s immediate surroundings that the novel’s quiet greatness lies . . . There is no right choice, no choice that can save her, and this ineluctability makes the novel so heartrendingly intimate that you can only cry as you approach the end.« – Victor Malm, Expressen

»[There] is a whiff in the novel that is unmistakably Fioretos, with grandly passionate clarity and cautious whispers, all at the same time. With politics, and what it is to be human – and close-ups, details, poetic frills in the damp and radiator-requiring chill of the Mediterranean winter. Fioretos has previously touched on the fracturing history of contemporary Greece; in Mary he goes straight to the core.« – Ulrika Stahre, Aftonbladet

Links

Talk with Malou von Sievers about the book, TV4, September 16, 2015