The Strange Pleasures of Jetlag

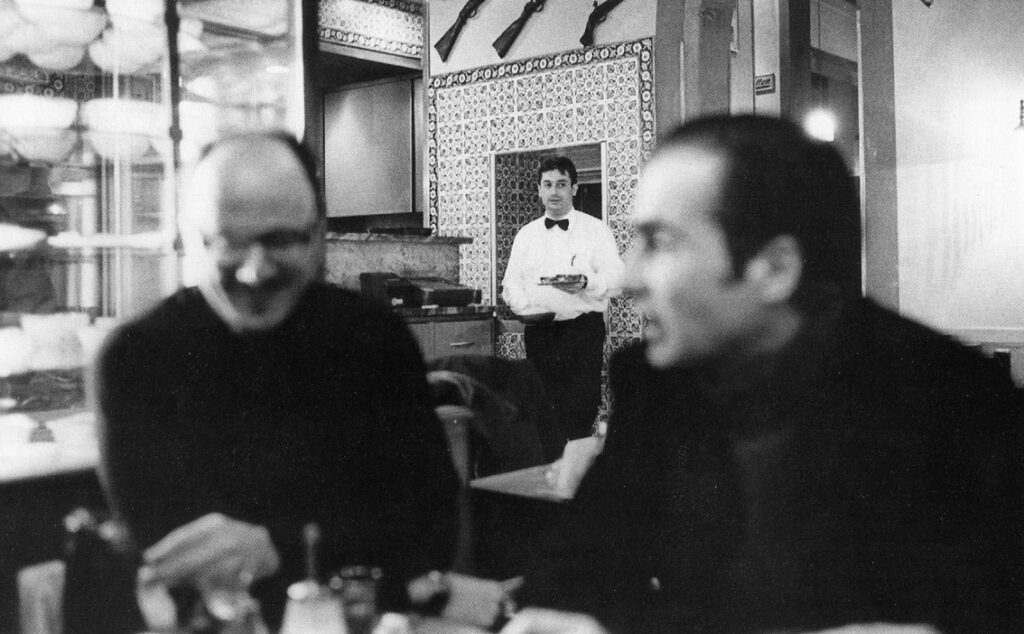

Conversation · Published in German · Literaturen · 2002, Nr 3, S. 33–37 · Photos by David Balzer/Zenit

Late January afternoon at a Turkish restaurant in Kreuzberg. Desolate flurries in the air outside, timid streetlights, frost-coated car roofs. Inside, at a table next to the vitrine containing pastries, illuminated in stark, white neon: two writers of more or less Greek descent. Conspiring whispers.

Aris Fioretos: Here we are, having breakfast at five in the afternoon. We both just returned after the holidays — you from Cozumel in the Gulf of Mexico, I from the decidedly less paradisiacal New York.

Jeffrey Eugenides: After eighteen hours on Scandinavian Airlines, no paradise could restore me.

Fioretos: I take strange pleasure in jet lag. For a week or so you’re out of sync: getting up when others go to bed, going to bed when others get up. Suddenly the body ticks to a different biological clock. When I have no obligations and my wife is elsewhere, I thrive. I stop shaving, survive on coffee and yogurt, and spend twenty-four hours in pajamas, most of them working. For once, you don’t have to live up to the fine print on the social contract. Old routines return soon enough. Once the rhythm is normalized, you realize that hot water and soap wouldn’t hurt, nor decent company . . .

Eugenides: As a writer you can either live like a bohemian in perpetual jetlag, living at night so to speak, even in the daytime, or you can choose family and children to give you a connection to a world. I like the solitary life, but a lot of the time it’s the solitary writer who becomes so self-obsessed that he no longer can write about anyone but himself. Having a family on the other hand may prevent you from reaching a deeper level of concentration. It’s a trade-off. Personally, I chose the latter. Stability seems to me a better shot in the long run.

Fioretos: Berlin used to be the metaphysical capital of jetlag. At least its Western half. Here, life was slower somehow, more insulated and self-conscious, yet diverse enough to allow minorities to thrive. It was a sociotope, affiliated, in spirit, with misfits from all strands of life. Also, it was cheap. Perfect for writers.

Eugenides: I still like it. I’m on my third year here. It’s a great city to work in. I’m not sure if I would feel this way if I were a Berliner or not. I mean, part of why it’s a good place for me to work is that I’m not from here and so distractions are at a minimum. That wasn’t the way it was in New York. I came to Berlin to get away from the publishing mania there and finish my book. Finally.

Fioretos: How long did it take?

Eugenides: Eight years. Two less than the Trojan War . . . Entitled Middlesex, the book is a comic epic, narrated by a hermaphrodite — not a mythical one, but a real-life one, born in Detroit in 1960. It’s sort of a family epic, or rather generational epic. If you have a name like mine that rhymes with Eumenides, I think you can’t help but deal with classical themes. I started the book long before I came to Berlin, but without this city I may never have finished it. I didn’t think Berlin would make it into the book, though finally it did. It snuck in in the last draft. But I better not say too much about the book before it has been published . . .

Fioretos: Another Greek quality: superstition.

Eugenides: Yeah, don’t talk about your book until it comes out! But maybe we could discuss this in general terms? My view is that epic literature isn’t just a thing from ancient times, but has remained alive in Western literature in the more fabulist writers. I’m talking about the great liars, Swift and Rabelais, obviously, but even people like Kafka and his heirs, Günter Grass and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. What is magic realism, after all, but the continuation of certain epic energies? The riverboat trip at the end of Love in the Time of Cholera, for instance, allows the characters to travel into eternity, the eternity of their love and old age. That’s closer to Homer than Hemingway. Although Hemingway is epic in the Spartan, heroic way.

Fioretos: Sparta versus Ithaca: perhaps these are the two extremes of the epic? On the one hand, the stoic and slender attempt to negotiate your way through thorny life. Be it as an agent behind the enemy lines of existence, as in Beckett or Lispector, or as a lone soul confronted with the immensity of sea or jungle, as in Hemingway or Conrad. On the other, the lush and lovely, cinematoscopic attempt to sample all the facets of life in its maddening splendor. Be it as an agent of memory, as in Proust or Woolf, or as the ventriloquist of an age or a city, as in Celine or Döblin. I confess I have a weakness for narratives that function as well-wrought lies, a Greek tradition if there ever was one. You know, the kind that slyly sings the beauty or decrepitude of the world, while furtively pulling your leg — but in a limber, indeed loving manner. Perhaps this is prose that hails neither from Sparta nor from Ithaca, but from Troy? One that is versed in the enchanting art of the contraband, smuggling what will prove to be the reader’s undoing in the innocent-looking belly of an artifact?

The Virtues and Vices of Family

Eugenides: Now you’re talking. Troy, that’s my genetic hometown. My grandparents were silk farmers in Asia Minor. As far as Trojan horses go, I agree with you that deception is a necessary element in writing fiction. But I think its deployment changes over time. I’ve always felt that postmodernism was in the main a continuation of modernism. The modernists, like the Abstract Expressionists, were eager to show the paint in their paintings. They wanted the literary text itself to be where the action was. In Joyce, the action happens on the page as much as it does “out there in the real world.” The postmodernists continued this trend by calling attention to narrative conventions and fictive artifice. Despite the ironic and occasionally superior tone of some of their writing, the basic urge was one of honesty. The old methods of transparency no longer convinced the reader. The paradox was this: to persuade the reader to believe in your story you had, at a certain point, to undermine that story. This has been going on since Tristram Shandy, of course, but the strategy became useful again during the 1970s, largely as an antidote to the slickness of the media. Everywhere you looked, you were being deceived — by advertising, by politics — so the defense to all that was to show up the artifice in fiction and re-establish a sense of trust in the reader. Where we come in is at the end of all that. American writers my age grew up with postmodernism and irony. We have it in our blood, but we are less doctrinaire in our approach. Postmodernism is like communism: better in theory than practice. It might sound thrilling to hear that narrative is finished, that there are no more stories to write, but if you follow that edict, the stuff you write ends up being arid, programmatic and literarily self-absorbed. Pretty soon the store shelves are empty. Writers like David Foster Wallace, Donald Antrim and Jonathan Franzen are postmodern to a greater or lesser degree, but all of them are committed to telling stories. While we have been brought up on modernism, I think may writers of my generation are trying to create a fusion of modernism, postmodernism and good old realism. Tolstoy by way of Pynchon. We want to follow Pound’s dictum to “make it new,” but we are aware that a certain kind of experimentalism is not at all new right now. New might be more a matter of voice or content than a matter of formal innovation . . .

Fioretos: As a reader, I enjoy the type of realist novel you describe, though not without certain apprehension. It seems to me to rely rather much on the principle of recognizability. The clash between generations is the engine driving this sort of epic. On the one hand, there is the younger’s predictable attempt to correct the habits of the older; on the other, the older’s dismay when they see perceived virtues treated as declared vices. Franzen shows both how incisive and how programmatic this confrontation may be in The Corrections, a realist novel more about family than about generation, packed with smart reflections, charming psychology and a little slapstick. Still, I demand more from a book than the mere affirmation of things I already know. I prefer a serious shot of madness or magic, some surprise and amazement, perhaps even an aberration or two. All of this, mind you, in the solid form of a story. Maybe I’m just not American enough . . .

Eugenides: I think recognizability is a major aspect of what the public tends to like in American fiction: to see themselves reflected in literature; to have someone describe the things they should be noticing but are not. Americans respond to that quite strongly. Franzen’s book is almost irreproachable in this regard. It gives you a realistic view of the world; through great artistic effort, it reproduces that world for you; and you are not going to be able to quarrel with its descriptions of America in the 1990s. My own book is more intuitively based. It is about something very few people know personally, hermaphroditism, which really has not been dealt with in this way.

Fioretos: Electing a hermaphrodite as a narrator, you’ve chosen someone who is sterile — that is, a person with whom the trajectory of a family terminates. In a sense, Middlesex must be about the end of the family epic. I like that. An American endeavor, if there ever were one. Naturally such termination can occur only in Detroit, that home of mobile solitude: the car.

Eugenides: Despite our obsession with identity politics, Americans also love stories about foreignness, about reinvention. Highsmith’s Tom Ripley is a good case in point. Right now, I think we’re at a stage where the whole multicultural movement is trying to connect to something prior to America. First everybody wanted in — and you had novels like Bellow’s Augie March, a book written by a Jew who made little of his Jewishness and declared in its opening line, “I am an American.” Now in the States people are trying to reestablish ethnic roots. There is a sense of history beginning before 1776.

Fioretos: In contrast, in Germany, the argument is often made that the family saga is impossible. The thesis seems to be that the time before 1933 and after 1945 can’t be bridged by generational epic. Another Buddenbrooks, written in light of racial politics and eugenic programs, is inconceivable. If nonetheless you use Mann as your model, you’re assumed to devote yourself to revisionism. Personally, I’ve never understood the greatness of Mann. But just because his work may have played out its role as literary ideal, it doesn’t follow that epic and family have ceased to exist as institutions. Posed in this manner, the argument is so typically German. It has to do with its literature’s fraught relation to the question of historical continuity. Perhaps a third postwar generation of writers will treat it with more sang froid. At any rate, the incessant talk of Vergangenheitsbewältigung gets on my nerves. Is the specific past intended really possible to “master” with greater or lesser degree of force? Isn’t it something you have to live with? And hence an inheritance?

Eugenides: History is not the negation of family. Personally, I would be very happy to be a German writer and to tackle these problems, to write a new Buddenbrooks which would start in the 1920s and end today. Or even better: a great Turkish-German family epic. I think that would be an incredible novel, one that would actually transcend national borders and be of interest to other countries as well.

Fioretos: If Anna Karenina and Buddenbrooks are the twin towers of the realist family chronicle, a book like Ada is more muddled in terms of its literary DNA. In Nabokov’s epic, too, generational processes are described. But it’s done with a heightened consciousness of language’s influence on our sense of self and the futility in attempting to understand human beings solely with reference to genealogy. Perhaps it’s because the love he describes is incestuous? To me, this aberration in the historical paradigm is a clear gain for literature. I imagine you’re after a similar disturbance in your book. At the very least, your narrator’s hermaphroditism must have affected what you term “voice.”

Eugenides: It nearly did me in. I spent over two years re-writing the first fifty pages of the book, trying to come up with the right voice. It was a tall order. Gender gave me a lot of trouble. On the one hand, the voice had to be elastic enough to convey experience from both a male and female point of view. In addition, it had to be capable, at some times, of narrating epic events in the third person and, at other times, of dramatizing psychosexual angst in the first person. At first I thought this meant the voice had to be “hermaphroditic” somehow. My narrator has a condition called 5-alpha reductase deficiency syndrome. With this condition, a person is born looking like a girl but then virilizes at puberty. By the time my narrator tells the story, he is ostensibly a man. That let me off the hook, to some extent. But it was not until I realized that my narrator was going to be as individualistic as any narrator and that, at the time of writing the book, he was male-identified enough, that I was able to tell the whole story. Finally I decided to do what nature does: to create a distinct person — with virtues, vices and all.

The Thing About Sex

Fioretos: Like books, humans are not compelling because of what they have in common with others, but by virtue of what makes them unique. Oddly, this very singularity is what they — or, for that matter, any good text — share most deeply with others. The true home of literature is not the nation but the library. Writers who don’t realize this end up producing illustrations rather than setting examples. In a way, it has to do with honesty. As long as you respect the idiosyncrasies of the characters you’ve invented, the text will be fine however flawed the lives described may be. Especially in mock epics, frankness is crucial. I doubt they’ll ever be convincing if their tone isn’t in collusion with their topic. Perhaps that is how honesty is engendered? Showing the seams of a text is part of the agenda — like saying to the reader: “We both know this is invention. Look, here are the ropes, the glue and the nails that hold the scenes together. But you’ll see, they’ll make you believe in the story . . .”

Eugenides: You raise the stakes . . .

Fioretos: Like a conjurer who shows you his hat and rabbit, but still manages to surprise you. It will only work if you don’t abuse the reader’s confidence. That’s why I mistrust the avant-garde novel in its classical form: it may have had its historical usefulness, but it tends to be too much in the reader’s face. There’s no grace, no cunning. And way too many meta-constructions. I suspect the novel can get farther, be more insidious and thought provoking, if it thrills. Lust and trembling are not bad principles for a writer. Why combat the world when you can reinvent it? Besides, I doubt any artifact can do without a little beauty in the long run.

Eugenides: You like ambiguity . . .

Fioretos: When I wrote my last novel, I wanted it to be like good sex — metaphorically speaking. Now, good sex is that uneasy balance between sincerity and seduction. So I needed lots of foreplay. The narrative couldn’t cut straight to the matter, but had to activate the reader, sense by sense, which meant that it didn’t catch steam until five, six chapters into the book. The novel I’m trying to complete now is different. On bleak days, I think it might be nothing more than a one-night stand: short and unsightly, with an irritated explosion at the end. Applying myself to these texts, I’ve realized that if the tone collaborates with the subject matter, your work will be believable no matter what improbable stunts it might try to pull off. Striking that balance is frightfully important. I don’t believe in novels that attempt to shock. They grant either tone or subject matter all the weight; they limp. But I am interested in the novel that tries to compromise the reader. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t wish the text to be mean or sound superior. But what would literature be if it weren’t lithe and wicked, seductive even? Perhaps this is the novel as Trojan horse? Of course, no writer in his right mind would like to slay the reader. But if you manage to compromise him in a manner such that it will be evident that the text is on the reader’s side — already in his midst, as it were, like Odysseus’s wooden animal — there’s a form of understanding to be won that is very intimate, very real. If you’re lucky, it may even give raise to that thrilling shiver along the spine that is the surest sign the text is worth the effort.

Eugenides: Your sexual metaphor reminds me of something else relating to where the novel is going. It’s this whole idea of hypertext, so beloved of Robert Coover and Mark Amerika. Roland Barthes claimed that the author is dead. In the author’s former place of privilege Barthes installed the reader. Nowadays, everyone wants to write his own stories, supposedly, to be given a variety of plots to choose from and to come up with the end himself. Well, I have never believed that. The pleasure of reading comes from being led by a superior talent to a place you would never have gotten by yourself. And here’s where your metaphor comes in. I mean, what’s better: having sex with yourself or with someone else?